On December 8, 1941, the drone of aircraft could be heard over Singapore harbor; the war in the Pacific had begun. That evening, two ships went on a daring attack against the Japanese. The battleship HMS Prince of Wales, and the cruiser HMS Repulse set out on what would be their last voyage.

Their commander, Admiral Sir Thomas Spencer Vaughan Phillips, could not stand by while the Royal Air Force and British Army were desperately fighting for their lives against a far superior Japanese force. He hoped that by attacking the rear of the Japanese army coming out of Singora, modern day Songkhla, he could cut their supplies and strand them on the beach. To do so, he selected Force Z, made up of HMS Prince of Wales, HMS Repulse, and four destroyers.

The Prince of Wales was one of the most advanced battleships of the time, with radar-guided firing control, 14-inch guns, and a heavy torpedo belt. She also had a new system called HACS or High Angle Control System, which was a radar targeting system for anti-aircraft guns. It gave the Prince of Wales an incredibly accurate array of anti-aircraft weapons.

The Repulse, on the other hand, was an aging battlecruiser. Launched in 1916 she had had an extensive career during WWI and between the wars. From the start of hostilities in 1939, she had patrolled the Atlantic and underwent multiple refits. When she departed from Singapore on December 8, while still an old man o’ war, she certainly had a fighting chance against a Japanese ship.

Philips, onboard the Prince of Wales, knew he was heading into a hornet’s nest, but believed he would be able to fight his way out and strike a decisive blow. The six ships of Force Z steamed out of Singapore, confident of victory.

From the beginning, mistakes were made. The Prince of Wales’ HACS was not operating properly, due to the heat and humidity of Singapore. It left them with limited air defense. Phillips believed that air power was only a minor threat to his force as at that point no active battleship had ever been sunk by aircraft. At Pearl Harbor, the ships had been docked and were caught off guard. Believing there was no significant threat from the air, Phillips declined the RAF’s offer of fighter cover for his sortie.

Within an hour of leaving port at 1710 on the 8th, the small squadron was spotted by Japanese aircraft. News of British battleships leaving Singapore spread quickly among the Japanese navy, and a flotilla of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers was assembled to respond. Both forces came within 9 kilometers of each other, but due to foul weather neither spotted the other, and the Japanese aircraft were not picked up on the Prince of Wales’ radar.

Then a Japanese plane dropped a flare over the cruiser Chokai, mistaking it for the Prince of Wales. The flare was spotted by the British, who thought their location had been discovered, so Phillips ordered the ships back to Singapore. On their return journey, reports came in of the Japanese landing nearby, and Phillips believed there might be an opportunity to recoup some of the failures of his mission.

At around 1000 on December 10th, while Phillips was searching for the Japanese landings, the destroyer Tenedos, which had been detached from Force Z, reported she was under attack by Japanese bombers. Unfortunately, though, a lone Japanese scout plane spotted the force near Kuantan and reported their position to the bombers. They broke off their attack on the Tenedos and spread out as they headed north.

The Japanese aircraft discovered Force Z at 1113, and eight Nell bombers attacked the Repulse. They scored only one hit and caused no serious damage. The crew was shaken, but their day was not over yet.

Around 1140, seventeen Japanese planes appeared on the horizon, diving down to torpedo height. The British ships pushed forward under a full head of steam, attempting to escape the air attack. Nine planes attacked the Repulse, and eight the Prince of Wales. The battleship’s crew fired at the low flying aircraft, taking one out, and damaging three others.

Despite their efforts, eight torpedoes sped towards the battleship, just below the surface. The captain pushed his engines to their capacity, attempting to escape. Taking evasive maneuvers, he avoided all but one of the deadly weapons.

A massive explosion rocked the port engine room. A torpedo had hit them at the point where their propeller shaft exited the ship, an incredibly lucky shot. The shaft, spinning at maximum speed, tore the damaged gasket which prevented the ship from flooding. Engineers fought the initial flooding and stopped the engine. While they attempted to repair the damage, the Japanese aircraft flew back to base, to report the attack.

Finally, the Prince of Wales’ engineers got the prop up and running again, but as she gained speed, the watertight gasket failed completely. 2,400 tons of water gushed through the prop shaft housing, flooding the compartment. The ship slowed from over 20 knots to 16, grinding almost to a halt. As the flooding spread through her port side, she began listing, tilting by over 11 degrees. All but two of her anti-aircraft guns were out of commission, and her starboard guns could no longer protect her against low flying torpedo bombers.

To compound their problems the Japanese returned at around 1220. Twenty-six Betty torpedo bombers swooped down on the floundering battleship. Another salvo of torpedoes skimmed just below the surface towards the exposed underside of the Prince of Wales. Three more hits rocked the ship, sealing its already tenuous fate.

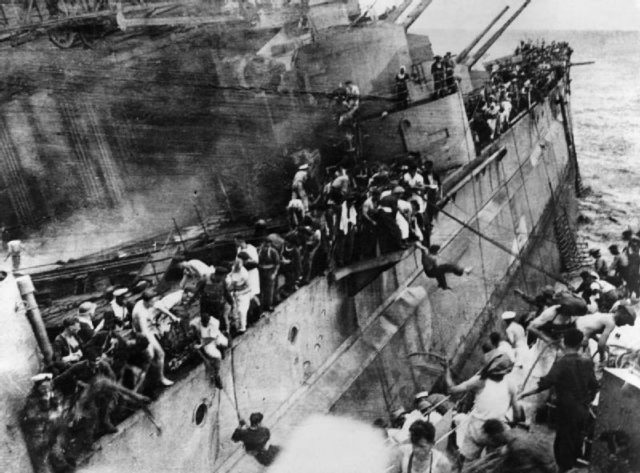

At the same time, torpedo planes attacked the Repulse from both sides. The pincer tactic worked, and the aging cruiser, which had so far dodged nineteen torpedoes, was struck four times in a row. She quickly took on water, and while her crew hopelessly tried to escape their sinking ship, she began to roll. By 1233 she had completely overturned, taking many of her 967 man crew with her.

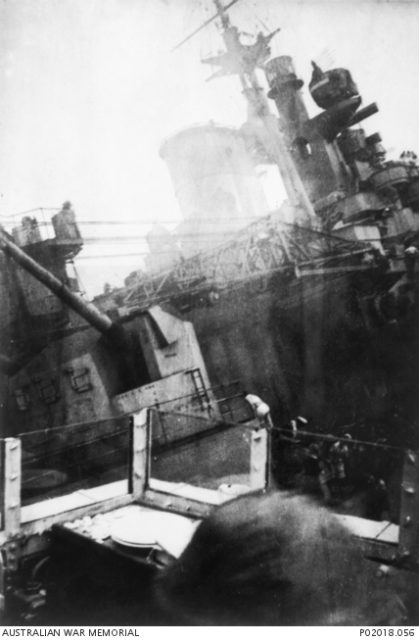

The Prince of Wales, barely afloat, but still fighting back with her two remaining 5.25-inch anti-aircraft guns, was being bombed. One bomb went through her deck amidships, hitting the makeshift hospital which was treating most of her wounded crew. She began to capsize to port, and HMS Express, a destroyer, came alongside to help offload the survivors. As the ship kept rolling, her bilge keel scraped along the destroyer’s side, almost taking her down as well.

By 1320 both the Repulse and the Prince of Wales were under water. The Japanese planes turned back to base while the destroyers desperately worked to rescue as many of the crews as possible. In all, over 1,000 crewmen were rescued, but 840 were lost to fire, explosions or the sea.

The Repulse and the Prince of Wales were casualties of the old world’s reliance on large surface fleets. In WWI the submarine had come of age, now less than 30 years later, the airplane ruled the waves. Even if the Prince of Wales’ HACS had worked, the Japanese air attacks would have persisted, and the outcome would likely have been the same.

The age of the battleship was over.