The romantic war film, The English Patient, was based on the novel of the same name by Michael Ondaatje, which was awarded the Booker Prize in 1992.

The film was the joint work of director, Anthony Minghella, and writer, Michael Ondaatje. In 1997, it received 12 Oscar nominations which resulted in nine awards.

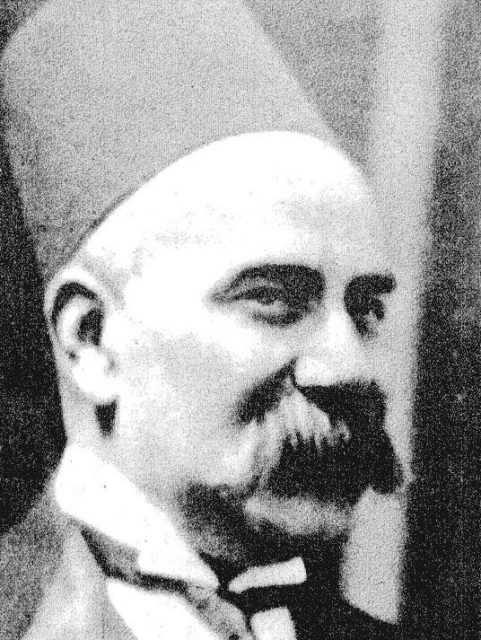

When creating his main character, Michael Ondaatje based him a real person: Hungarian aristocrat, desert researcher, and aviator, László Almásy.

However, the real Almásy was a far cry from the romantic hero of the film who conquered women’s hearts. In 2010, several documents were declassified that showed his homosexual inclinations.

It turned out that Almásy was in love with a German officer named Hans Entholt who fought in North Africa. In addition, Heinrich Barth, an employee of the Institute of African Studies who studied the letters of Almásy, confirmed, “Egyptian princes were among Almásy’s lovers.”

László Almásy was born to a noble family on August 22, 1985, in the Hungarian town of Borostyánkő. He was educated at Berrow School in Eastbourne, England.

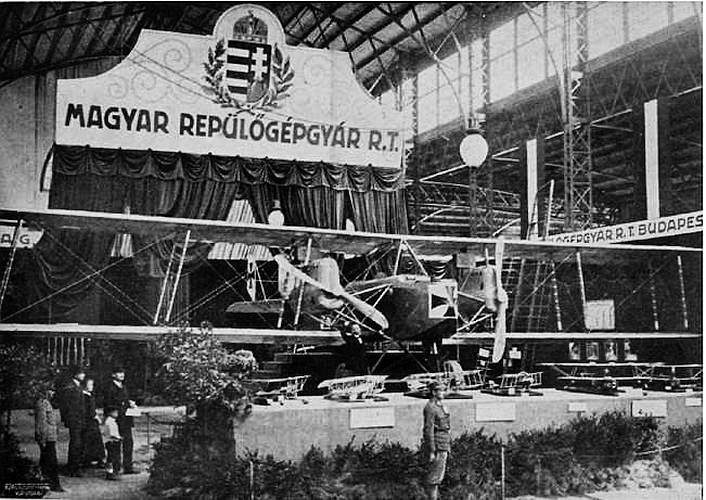

During the First World War, Almásy served in the Air Force of Austria-Hungary. In the post-war period, he supported the king of Austria in an attempt to regain the throne.

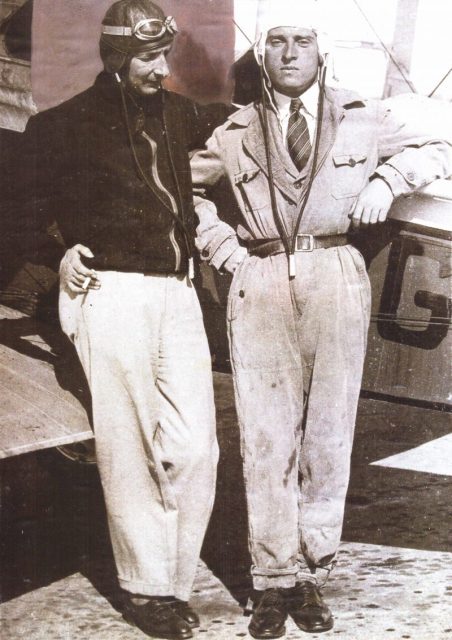

After the war, he returned to Eastbourne and became a member of the Eastbourne Flying club where he learned to fly a glider.

He also took part in numerous car races on behalf of the Austrian car company, Steyr. The commercial interests of this company led Almásy to Africa where he organized safaris for European tourists and drove cars along the 700-kilometer road.

In the 1930s, Almásy began exploring North Africa. He formed an expedition consisting of three Britons (Squadron Leader H.W.G.J. Penderel, Patrick Clayton, and Sir Robert Clayton) to find the lost oasis of Zerzura. Almásy explored about 772,000 square miles of the Sahara, but could not find Zerzura.

However, the trip resulted in producing a catalog of prehistoric rock art. The drawings were found in the Cave of Swimmers in the Jebel Uweinat and Gilf Kebir massifs. However, it is worth noting that Almásy was not the discoverer of Gilf Kebir, which had previously been accidentally discovered by the Bedouins.

Sir Clayton had sponsored Almásy financially, but he died in 1932. However, this did not stop the explorer who soon found a new sponsor in the form of Prince Kamal el Dine Hussein.

He organized a new expedition which discovered Wadi Talh (the third valley of Zerzure) and the prehistoric rock paintings of Ain Dua at Jebel Uweinatt.

In addition, while traveling in Nubia, Almásy managed to find a tribe of Magyarabs who spoke Arabic but considered themselves descendants of Hungarian soldiers.

In subsequent years, Almásy worked in Egypt as a flight instructor and conducted ethnographic and archaeological expeditions together with German ethnographer, Leo Frobenius.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, Almásy was not allowed to stay in Egypt due to worries about espionage. He was forced to return to Hungary, which joined the Axis countries after the signing of the Berlin Pact.

In Budapest, due to his experience in the First World War, Almásy was called upon to join the German Africa Corps in the rank of captain of the Hungarian Air Force.

In the period from 1941 to 1942, he served beneath Erwin Rommel. During the operation of Salam, Almásy ferried two German spies across the front line. The preparation and planning of the operation took several months, and due to the changing situation at the front, the start was repeatedly postponed.

During the operation, Almásy and his group moved around in two stolen US trucks and two Chevrolets. Despite the route, the operation ended with a successful crossing of the border by two German agents: Johannes Eppler and Hans Gerd Sandstede.

After that, Rommel elevated Almásy to the rank of major and awarded him the Iron Cross (First Class).

In between military operations, Almásy got together with a young German officer of the Africa Corps, Hans Entholt. Sadly, Entholt died in 1943 after stepping on a mine during the retreat.

After the end of the war, Almásy returned to Budapest, where sometime later he was arrested by the communist authorities on charges of war crimes and high treason.

The charge was based on his wartime book which had been placed on the banned books list. However, this meant that neither the judge nor the prosecutor in the case had read the offending volume. Eventually, Almásy was released, thanks to some influential friends.

Sometime later, he was again arrested. With the alleged help of British intelligence and Alaeddin Moukhtar, who was a cousin of King Farouk and bribed Hungarian communist officials, Almásy was able to flee the country.

He used a false passport under the name of Josef Grossman to get him to the British part of occupied Austria. Ronnie (Waring) Valderano accompanied him. When KGB agents began persecuting Almásy, Waring put him on a plane to Cairo.

It should be noted that there is no convincing evidence that British intelligence helped Almásy. While that is certainly how the story goes, any corroborating information is contained within unpublished intelligence files.

Almásy returned to Egypt where, at the invitation of King Farouk, he became Director of the Egyptian Desert Research Institute.

In 1951, during his visit to Austria, Almásy became seriously ill with amoebic dysentery. Due to complications caused by the disease, he died in a hospital in Salzburg on March 22. He was buried in the public cemetery of Salzburg.

Read another story from us: Rommel Defeats the Free French: Battle of Bir Hakeim

In 1995, Hungarian aviation and desert enthusiasts placed an epitaph on his grave that reads: “Pilot, Saharaforscher und Entdecker der Oase Zarzura” (Pilot, Sahara Explorer, and Discoverer of the Zerzura Oasis).