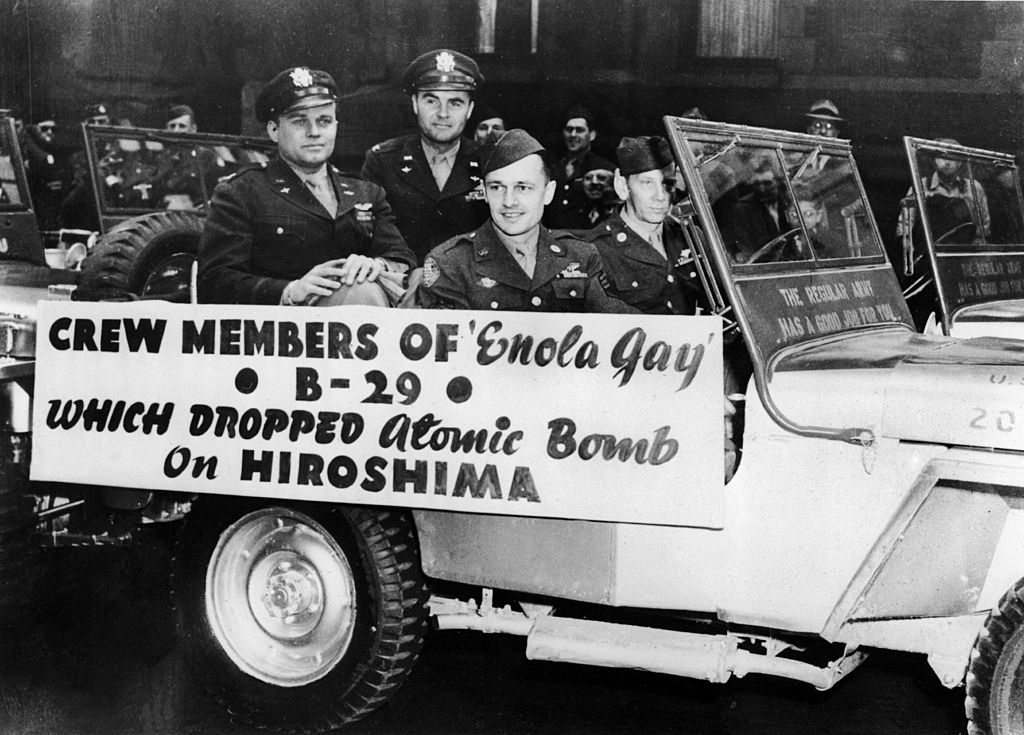

On August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. The plane is a B-29 Superfortress which had been named after pilot Paul Tibbets’ mother.

In order to carry the enormous weapon, the plane had been stripped of anything non-essential. This made it thousands of pounds lighter than a typical B-29 and allowed it to carry the 10,000 pound atomic bomb.

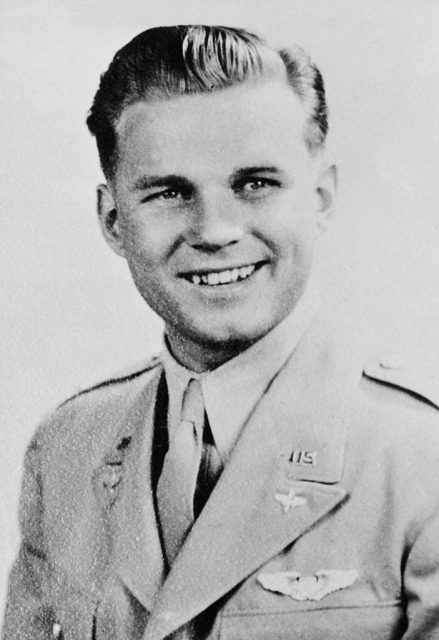

According to the plane’s navigator, Theodore Van Kirk “Immediately [Tibbets] took the airplane to a 180° turn. We lost 2,000 ft. on the turn and ran away as fast as we could. Then it exploded. All we saw in the airplane was a bright flash. Shortly after that, the first shock wave hit us, and the plane snapped all over.”

With this act, World War II was essentially over, the atomic age was officially begun, and the debate over the ethics of atomic weapons has continued for the more than 70 years that have passed since the attack.

After completing its mission, the Enola Gay returned to its base on Tinian Island.

On August 9, 1945, the Enola Gay flew again. This time it gathered data about the weather in the lead up to dropping another atomic bomb – this time on Nagasaki. She flew a few more times after the war as it was used in an atomic test program in the Pacific.

The Enola Gay was stored at an airfield in Arizona before being flown to Illinois. It was transferred to the Smithsonian in July 1949 but was stored at an air force base in Texas.

The last time the Enola Gay flew was in 1953. On December 2 of that year, it flew to Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. It sat there until August 1960 when preservationists from the Smithsonian worried that anymore time spent outside would leave the plane too damaged to repair. It was taken apart and the pieces were taken inside.

When the 50th anniversary of the atomic bombings arrived, the Smithsonian had already spent almost ten years restoring the plane to be displayed in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. The proposal for the planned anniversary exhibit was protested by Air Force veterans.

They were alarmed at the way they saw the exhibit portrayed the US as the “unfeeling aggressor” while playing up the Japanese casualties of the bombs.

In the end, a heavily revised version of the exhibit went on display. When it opened, it only displayed half of the Enola Gay. Restoration work was still ongoing.

When the exhibit closed in 1998, approximately 4 million people had visited. It was the most people ever to visit an exhibit at the Air and Space Museum until that time.

In 2003, the full plane was placed on display. That generated more protests, but the plane is still on display in the museum.

Another Story From Us: Pearl Harbor Veteran Passes Away at Age 100

The crew aboard the plane on that fateful day were aware of the enormity of the event. Van Kirk said that the crew immediately knew that the war was over. Co-pilot Robert A. Lewis wrote in his log that he was “groping for words” to explain what had happened. He settled for “My God what have we done.”