The Japanese used special bombs filled with infected fleas and dropped them over Chinese territories.

If you say “army” or “weapons,” most people think of the traditional human army and metal weapons. Few people would automatically think of insects as a weapon to be deployed.

Not many would consider that a mosquito bite could be anything other than accidental or irritating, or that the Colorado potato beetle was sent purposefully to a potato field. But in these assumptions lie the whole beauty and horror of insects as a biological weapon.

Utilizing insects to attack the enemy is referred to as using an entomological weapon. Using insects for military purposes was a method employed in ancient times, but it has grown to a new scale in the 20th century.

Despite the gradual decline of entomological weapons, the presence of insects in various wars managed to gain monstrous glory.

There are three types of entomological warfare. The first type involves purposefully infecting insects with a pathogen and then releasing them over enemy territory. These insects then infect humans and animals through bites.

The second type is when insects are used for the destruction of agricultural plants, depriving the enemy of food sources.

The third type of entomological weapon involves the use of non-infected insects, such as wasps or bees, for a direct attack on opponents.

Jeffrey Lockwood, in his book Six-Legged Soldiers, suggested that the earliest incident of entomological warfare was the use of bees by ancient people. In order to force the enemy out into the open, nests of bees were thrown into shelters or caves.

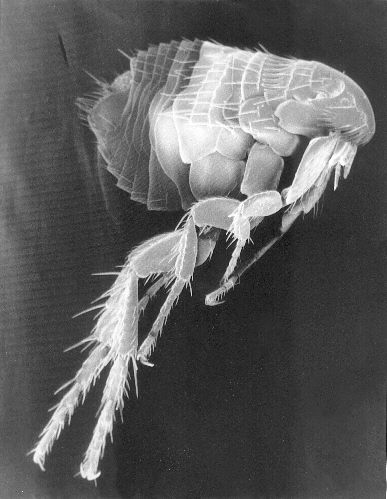

Furthermore, Lockwood suggested that the Ark of the Covenant could have been dangerous because it contained deadly fleas.

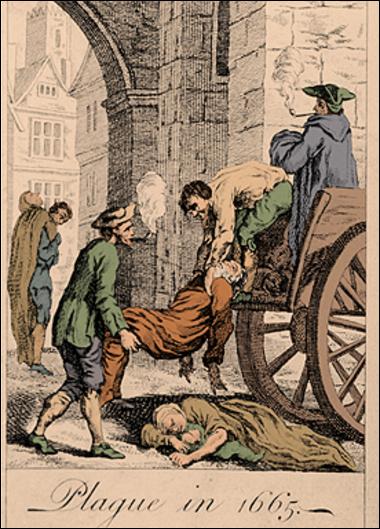

There is a story that one of the first uses of entomological weapons was the plague epidemic in the 14th century in Asia Minor. The consequences of this epidemic are known as the “Black Death,” which led to the demise of 30-60% of the population of Europe.

Many historians think that the Black Death probably came to Europe because of a biological attack using fleas. They were carriers of plague from the Crimean city of Kaffa (now Theodosius).

During the American Civil War, the Confederates accused the Union of intentionally spreading harlequin bugs throughout the territories of the South. However, these charges did not have direct evidence, so there is a possibility that the bugs got to the South in another manner.

Scorpion grenades are one of the oldest contenders that occurred about 2,000 years ago. During the military campaign against Mesopotamia, the Roman emperor Septimius Severus was forced to stop in front of the fortress of Hatra which was surrounded by impregnable walls.

Instead of a bloody assault on the fortress, the Romans began to collect poisonous scorpions and throw them at defenders. It is unlikely that many of the Hatra warriors died in this way. However, the Romans combined this assault with a strong psychological attack that ultimately forced the defenders to surrender.

The Romans also used beehives as improvised biological bombs. Their example was followed by many other nations from ancient times to the present day.

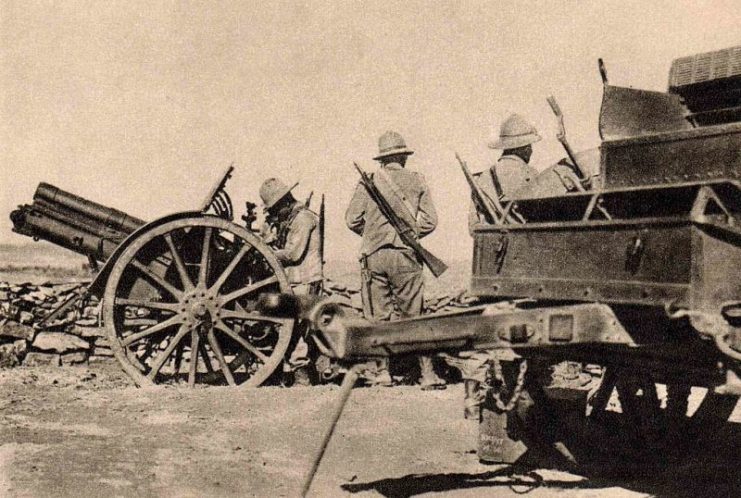

For example, during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936), Ethiopian soldiers used bees to fight Italian tanks. Getting a beehive inside a tank turned the vehicle into an unpleasant trap, and the crew had no choice but to evacuate.

Bees have been used in other ways. One of the simplest (and, at the same time, unsafe) examples involved the tactics of the Nigerian Tiv people. During the battle, they put bees in wooden tubes, aimed the tubes at the enemy, then blew the insects out.

A more reasonable, original, and reliable method was used in the medieval castles of England, Scotland, and Wales. Within the walls of some of the fortresses were areas purposefully created to keep a large number of bees. In peacetime, these bees quietly collected honey, but in the event of a castle siege, they would attack the enemy, defending their own home.

Relatively recently, it was discovered that bees have an excellent sense of smell, so the idea arose to use them both for demining and searching for drugs at customs. Croatian biologists think that bees could be better than dogs at these tasks.

At first glance, fleas as entomological weapons look less dangerous than bees, but this is not so. During World War II, Japan used plague-infected fleas to experiment on prisoners. Then, special bombs filled with infected fleas were dropped over Chinese territories. The result was an epidemic that took the lives of about 500,000 people.

It is known that the Japanese had planned to use plague fleas in 1944 on the Mariana Islands, which had been captured by the American forces.

During the Second World War, in addition to fleas, the Japanese also used flies infected with cholera against the Chinese population. However, flies showed less efficiency in infection rates than the plague fleas, so they were kept as a fallback.

During tests in the USA in the 1950s, mosquitoes infected with yellow fever were placed in bombs. They were considered a promising weapon in case of war against the USSR. Yellow fever in the Union was not a common disease and, therefore, the population was not immunized.

The Colorado potato beetle as an entomological weapon is aimed at the destruction of the enemy’s food sources. There is no accurate data on the use of the Colorado potato beetle as a biological weapon in many other countries, although it is known that experiments to create such weapons were carried out in Nazi Germany.

In addition to the Colorado potato beetle, Nazi Germany also planned to use malaria mosquitoes against their enemies. Tests were carried out on concentration camp inmates. Documents about this were presented to the public in 2013 in the publication of the journal Endeavor. One way or another, the military use of Anopheles mosquitoes did not happen.

One variety of entomological weapon that might be deployed in the future is cyborg insects.

By using electrodes and securing electronic “backpacks” onto the backs of insects, scientists have developed essentially living machines that can be controlled from a distance and used for military intelligence purposes.

Such insects do not use energy in the form of batteries which is an immediate advantage, but they are also small and therefore have other advantages over the classic UAVs.

Read another story from us: A Sticky Situation: Super Glue in Warfare

Surprisingly, insects have long been a part of warfare. The Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention of 1972 doesn’t specifically ban the use of insects in future conflicts, but it is certainly drafted wide enough to include them in its prohibitions. Whether this is enough to deter future armies from using this versatile, living resource remains to be seen.