War hero or anti-Semitic Nazi villain? Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is, to this day, the subject of heated debate – a historical enigma once praised by Winston Churchill himself as “a very daring and skillful opponent.”

He was the “Desert Fox,” revered by Allied Forces for his supposed chivalry, and allegedly implicated in the “Valkyrie” plot to assassinate Hitler. But how much about the man do we really know?

Who Was Erwin Rommel?

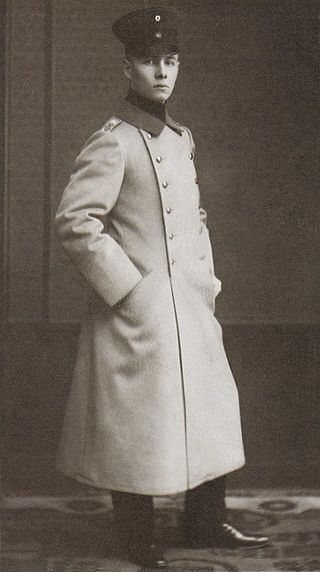

Born in the town of Heidenheim an der Brenz in 1891, young Erwin Rommel came from a middle-class family. His father, Erwin Rommel Senior, was a teacher. His mother, Helene von Lutz, was the daughter of a local city councilor.

His proficiency in strategy no doubt stemmed from his analytical and mathematical mind. From an early age, Rommel had an interest in engineering. Despite his desire to become an aeronautical engineer, however, Rommel’s father urged his son to go into military service.

Rommel would become the first in his family to remain in the military long term. Though he was initially rejected by the engineering and artillery divisions of the army, in 1910 the 18-year-old Rommel was accepted as a cadet in the German infantry.

He was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1912, and in 1914 he joined the 124th Württemberg Infantry Regiment, in which he served during World War I. This would be the beginning of his highly successful and decorated military career, during which Rommel became known for both his bravery and cunning.

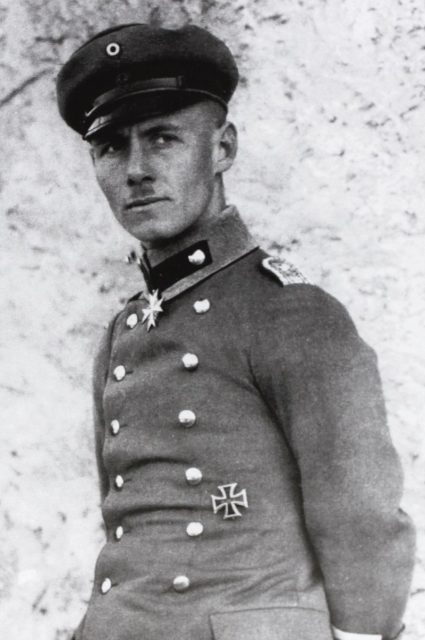

His efforts during the WWI earned him an Iron Cross and the Pour le Mérite, Prussia’s highest military honor, awarded by Kaiser Wilhelm II himself.

The Man vs the Myth

Rommel met Hitler in Goslar, Germany in 1934, while Rommel was posted as battalion commander. Hitler’s charisma and promises to reestablish Germany as a world power after the crippling results of World War I inspired Rommel to become a fervent supporter of the Nazi Party.

The two men had several encounters following this, and Rommel rose through the ranks on Hitler’s personal recommendation. But it was ultimately Hitler’s liking for Rommel’s book Infantry Attacks that led to his becoming the commander of Hitler’s personal guards during his tour of the Sudetenland.

Hitler and Rommel’s relationship was an interesting and somewhat fickle one. On more than one occasion, Rommel flouted direct orders from the Fuhrer.

In 1940, Hitler sent Rommel to command the German Afrika Korps and help the Italian army against the British troops in North Africa. Rommel turned the situation around for the Axis Powers, which is how he earned the name “Desert Fox.” He was also promoted from Major General to Field Marshal.

When the Afrika Korps went up against the Free French forces at Bir Hakeim, Hitler insisted that the French were renegades guilty of treason and were not to be captured but executed. Rommel never passed this command on to his men, sparing the Frenchmen’s lives.

In October 1942, the British finally overwhelmed Rommel and his troops near El Alamein in Egypt. Hitler demanded that Rommel and his men “show them no other road than that to victory or death.”

Once more, Rommel disobeyed. After fighting his way through the desert, he elected to spare his men from being massacred. He and several of his troops escaped, and he returned to Europe in 1943.

During his time in North Africa, the Rommel legend – or myth – grew. The Allies respected his battle tactics and the fact that he led from the front, unlike most officers. His men viewed him as a moral and humane leader.

The “Rommel Myth” was further perpetuated by the British press, which sought to portray the British troops as fighting in North Africa against a noble foe – largely because they couldn’t defeat him for some time.

When Rommel was implicated in a plot to kill Hitler, tales of his heroism spread even more, though many historians refute this heroism entirely.

Personal accounts from officers stationed in North Africa with Rommel have suggested that he was not entirely pro-Nazi. Rudolf Schneider was a young Afrika Korps soldier who served under Rommel during the North Africa campaign.

Schneider, interviewed by the Independent in 2009, said: “When the propaganda photographs were taken of our unit, they would drape Swastika flags over the vehicles. When the cameramen went away, Rommel would order the Swastikas to be taken away.

“He didn’t like Nazi insignia and took it off. He said, ‘I am a German soldier.'”

Was Rommel an apolitical soldier, as some have suggested? Just how much did he know about Hitler’s “Final Solution”? One can speculate that as one of Hitler’s most senior officers, surely he would have been privy to that kind of information.

There is also the burning question of Rommel’s knowledge of Einsatzgruppe, an SS death squad that was on standby to be deployed with the sole purpose of killing Jews in Palestine en masse. They were intended to be attached to the Afrika Korps, but Rommel was defeated at El Alamein before they could join his troops.

Only Rommel himself could enlighten us as to what his real motivation was. Many historians suggest that he was simply an ambitious soldier who chose to overlook Nazi atrocities in the interest of advancing his career.

The Assassination Plot

On July 20, 1944, after a failed attempt on Hitler’s life, a manhunt was launched for the perpetrators. Thousands of potential suspects were arrested and brutally interrogated. Many died.

Several confessions – more than likely delivered under extreme duress – implicated Rommel. Some claimed that he was simply aware of the plot but didn’t act, while others claimed he was directly involved.

In September 1944, Hitler received word of all the “evidence” that pointed to Rommel. At the time Rommel was recovering from serious head injuries, the result of a car crash due to a Spitfire attack.

Hitler was aware of Rommel’s almost universal popularity and status as a hero, and decided to handle the matter quietly for diplomatic purposes. His envoys gave Rommel the “option” of committing suicide to save his family from torture or death.

On 14 October 1944, accompanied by two Nazi generals, Rommel bid farewell to his wife and children. He was driven away from his home by his military escorts, and took a cyanide pill on a quiet, Blaustein country road.

Today, the majority of historians believe that Rommel had absolutely no knowledge of the plot to kill Hitler, and remained loyal – if not to Hitler, then at least to the institution of the German military – until his death.

Rommel Memorials

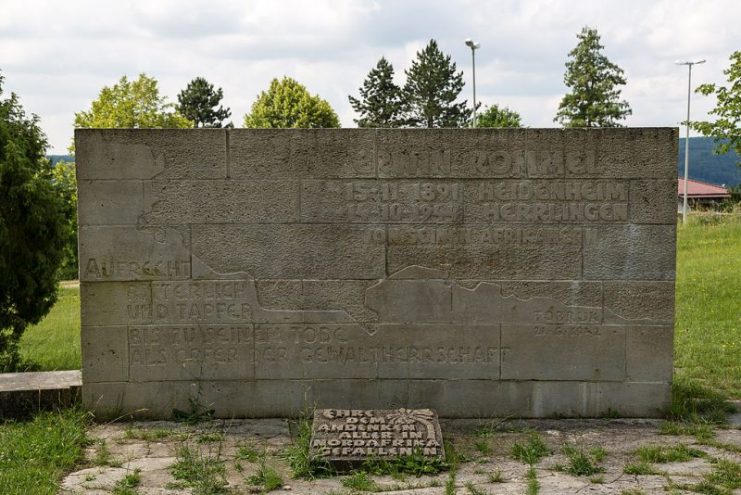

From 1961 to 2013 in the German town of Heidenheim an der Brenz, a memorial to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel stood unashamedly up on a hill, an imposing stony presence in an otherwise unobtrusive town.

The words inscribed on the monument called Rommel “Upright, chivalrous and brave until his death as a victim of tyranny.”

It was only in 2011 that protests over a memorial erected to a Nazi officer led to it being defaced. Ultimately, with consensus from the townspeople, historians and even representatives of the Afrika Korps, it was dismantled in 2013.

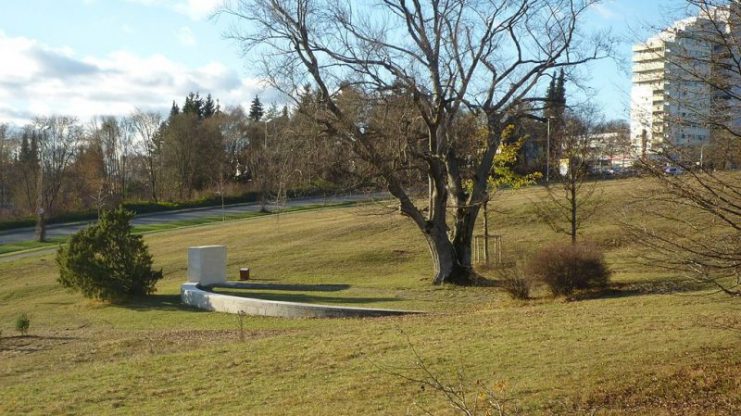

One monument to Rommel still stands today, at the site of his suicide in Blaustein. The inscription on the stone reads: “At this place, on 14 October 1944, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was forced to commit suicide. He took the poison cup and sacrificed himself to save his family’s life from Hitler’s Nazi henchmen.”

A noble epitaph for an enigmatic and ambiguous historical figure. The historical picture of the Desert Fox is a patchy tapestry of contradictory accounts and myth.

His heirs and many Rommel enthusiasts would have us believe that he was a mighty and just Desert Fox, while author and historian Wolfgang Proske, among others, claims he was a dedicated anti-Semite and even used Jewish slave labor.

There is often a double standard in historical accounts that chooses to forget faults in favor of creating lasting legends or tales to tell. Could it be that this is the case with Field Marshal Erwin Rommel? We may never know.