Eugene Bullard was the first Black American military pilot, flying combat missions for France during the First World War. He left the United States with hopes of a better life without racial segregation and found what he was looking for overseas. Life later saw him return to the US, where he found his exploits in France were largely unknown.

Early life and journey to Paris

Eugene Bullard was born on October 9, 1895, in Columbus, Georgia. During his youth, he witnessed a White mob attempt to lynch his father. While the elder Bullard expressed a belief that African-Americans needed to maintain their dignity in the face of White prejudice, his son dreamed of moving to France, where slavery had been abolished and Black citizens were treated better.

At the age of 11, Bullard ran away from home, with the aim of somehow making it to France. After stopping in Atlanta, he joined a group of English gypsies traveling across Georgia, for whom he began tending horses. It was through this group he learned England, too, no longer had a racial color line, and switched his sights there.

After learning the gypsies didn’t intend to return to England, Bullard went to work for a family in Dawson, Georgia. In 1912, he traveled to Norfolk, Virginia, and stowed away on the German freighter Marta Russ, which brought him to Aberdeen, Scotland. He then made his way to Glasgow, before settling in London.

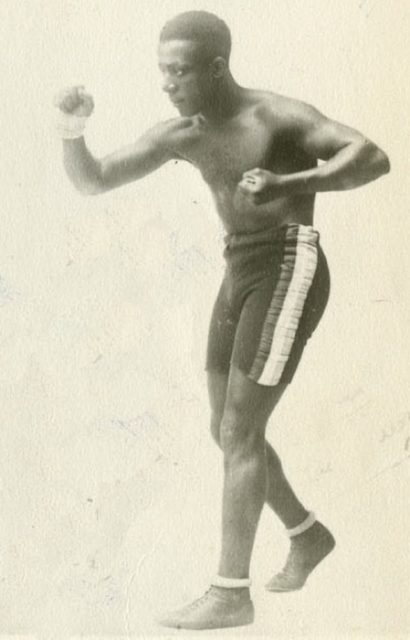

While in England, Bullard joined the Freedman Pickaninnies, an African-American slapstick troupe. He was also employed as a dock worker and as a target for an amusement park attraction. He began boxing, training under famed boxer Dixie Kid, who arranged for him to fight in Paris. He became enamored with the city, saying, “It seemed to me that French democracy influenced the minds of both black and white Americans there and helped us all act like brothers.”

He continued to box in Paris until the start of World War I.

Military service and aviation during World War I

On October 14, 1914, Bullard enlisted in the French military and was assigned to the 3rd Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion. In 1915, he served as a machine gunner and saw combat during the Battle of the Somme. He was also at Artois, and fought during the second Champagne offensive along the Meuse River.

While fighting during the Battle of Verdun as part of the 170th French Infantry Regiment, he was seriously injured by an exploding artillery shell, which ripped through his left thigh, narrowly missing his femoral artery.

While recuperating from his wounds, a friend bet him $2,000 to learn how to fly. In October 1916, he volunteered for the French Air Service as an air gunner and was sent to Aerial Gunnery School in Cazaux, Gironde. He then underwent flight training at Avord and Châteauroux and received his pilot’s license from the Aéro-Club de France on May 17, 1917.

Following his training in Avord, he joined the Lafayette Flying Corps with other American-born aviators serving with the French Air Service. Those with the corps flew alongside French pilots in squadrons across the Western Front. In June 1917, Bullard was promoted to corporal, and two months later was assigned to Escadrille Spa.93.

During this time, he took part in 20 combat missions. He was also a unique flier, bringing with him a monkey named Jimmy, and was nicknamed the “Black Swallow of Death” due to his race and the fact the 170th French Infantry Regiment were referred to as the “Swallows of Death.”

When the US entered the war, the US Army Air Service convened a medical board to recruit Americans serving with the Lafayette Flying Corps for the American Expeditionary Forces. Bullard was not chosen. While told it was because he wasn’t a first lieutenant or an officer, he later learned it was because of his race.

Bullard was transferred to the service battalion of the 170th Infantry Regiment in January 1918, after getting into an argument with a French commissioned officer, and continued to serve after the Armistice.

Success during the interwar years

Following his discharge from the French military, Bullard returned to Paris, where he worked as a jazz drummer at Zelli’s. He secured a club license for the establishment, which allowed it to stay open past midnight. Before long, it was the most celebrated nightclub in Montmartre.

He also visited Egypt for a time, where he fought two prize fights and performed as part of a jazz ensemble at Hotel Claridge.

Upon his return to Paris, he managed Le Grand Duc nightclub, purchasing the establishment in 1928. He hired musicians to perform at private parties and gained a host of famous friends, including poet Langston Hughes, French resistance member Josephine Baker, air ace Charles Nungesser, and musician Louis Armstrong. Eventually, he became the owner of a second nightclub, L’Escadrille.

His fame in Paris was so notable that author Ernest Hemingway based a character on him in his 1926 novel, The Sun Also Rises.

Bullard also opened an athletic club, which offered boxing, ping pong, hydrotherapy, and massage. He also worked as a trainer for boxers Victor “Young” Perez and Panama Al Brown. In 1923, he married Marcelle Straumann. The pair separated in 1935 and Bullard gained custody of their children.

Espionage and service during World War II

When the Second World War began, the French government asked Bullard to spy on the Germans who frequented his nightclub.

Following the German invasion of France, he volunteered for and served with the 51st Infantry Regiment, defending Orléans during the Battle of France. He was wounded by an artillery shell and fled to Spain, before returning to the US in July 1940. He spent time recuperating in a New York hospital, but never fully recovered from his injury.

For his service, he received 14 medals and decorations, including the Croix de Guerre, the médaille Militaire, and the Croix du combattant volontaire 1914-1918.

Little recognition in the United States

Bullard’s notoriety didn’t follow him across the Atlantic. He was unable to regain his Paris nightclub, as it had been destroyed during the war. He purchased an apartment in Harlem with a financial settlement he received from the French government. During this period, he worked as a security guard, a perfume salesman, a longshoreman, and as an interpreter for Louis Armstrong.

In 1949, Bullard was beaten by a mob during the Peekskill Riots in August 1949. The attack was prompted by a concert held by entertainer and activist Paul Robeson to benefit the Civil Rights Congress. Before Robeson arrived, a mob containing local law enforcement and members of the state attacked the audience. A total of 13 people were injured, including Bullard.

The concert was postponed until September 4, 1949, and occurred without incident. However, as concertgoers were leaving the venue, rocks were thrown at their windshields by a crowd of hostile residents.

In 1954, Bullard was invited by the French government to rekindle the everlasting flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier under the Arc de Triomphe. Five years later, General Charles de Gaulle made him a knight of the Légion d’honneur, calling him a “true French hero.”

His last job was as an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center. On October 12, 1961, he died of stomach cancer at the age of 66 and was buried with military honors in the French War Veterans’ section of Flushing Cemetery in Queens.

Following his death, Bullard received many posthumous honors, including being inducted into the inaugural class of the Georgia Aviation Hall of Fame in 1989 and being named a second lieutenant in the US Air Force in 1994. The Museum of Aviation in Warner Robins, Georgia also erected a statue in his honor.