Today we are familiar with the differences between dress uniforms, fatigues, and combat gear, but military uniforms are a relatively recent invention in the Western World. What we know as a dress uniform today was what soldiers from previous centuries were expected to wear during combat.

Cromwell’s New Model Army dressed its foot soldiers in red coats. The coats were purchased from the lowest bidder, and Venetian red dye was the competitive choice in the mid-1600’s. The result was impressive and terrifying, and served the British military well for more than two hundred years.

Even so, one problem the British had was that no dye was colorfast enough to maintain the uniform in its original red state. Too much sunlight faded it to pink, and excessive rain turned it purple.

Despite this, the uniform became part of a global military mythology associated with the success of overseas campaigns during the European Imperial era.

However, times change. As firearms became more precise in targeting and range, and as battles evolved into long-range firestorms, the advantages of the red coat diminished. No soldier wants to be an easy target for sniper fire, and no general needs to lose valuable fighting assets.

The white cross bands on a Victorian soldier’s chest may have looked distinctive, but probably served to shorten the life of many men before the British adopted khaki in 1902.

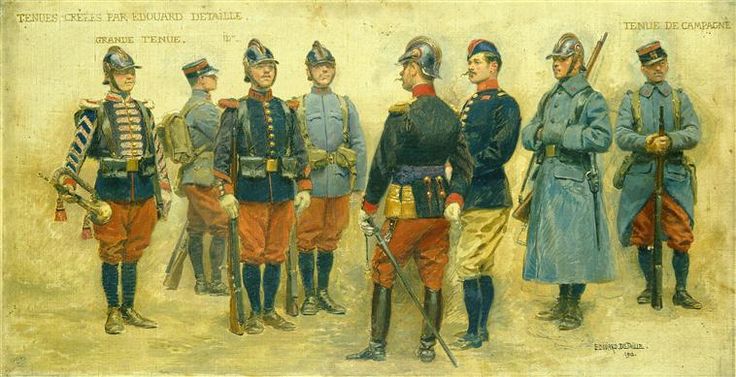

Other European armies were slower to change. To his great credit, the French Minister for War, Adolphe Messimy, realized that the red trousers and blue coats of his infantry made them vulnerable while fighting in the Balkans War of 1912-13.

However, he found it impossible at the time to implement changes. One of his successors would bring in a ‘horizon blue’ uniform a few years later, when France was some months into the First World War.

France led the way in changing headgear for everyone: it was the first country to introduce steel helmets, in response to the perils of trench warfare in WWI.

By December 1915 more than three million M15 ‘Casque Adrian’ helmets had been produced. Eventually, production of the helmet ran to more than twenty million.

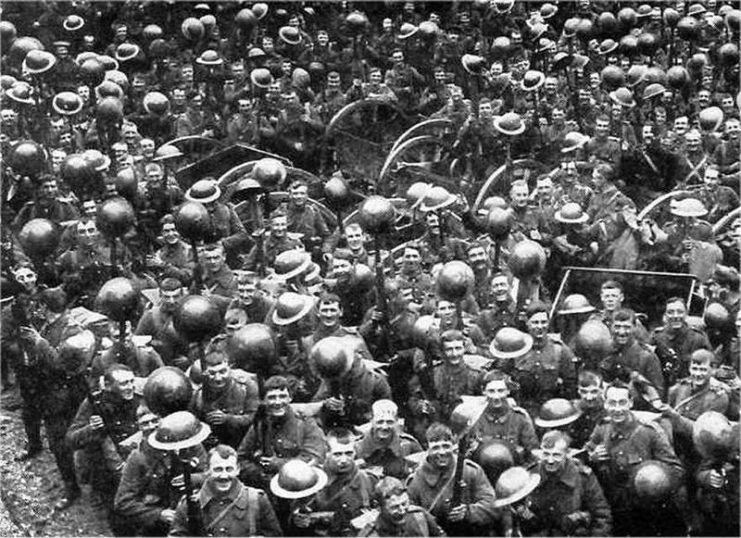

The British were not too far behind, but the war was eating up the production of steel for weaponry, and so there were only fifty helmets issued per battalion at first. It was April 1916 before enough of their so-called ‘Brodie’ helmets had been produced for all ranks to be able to wear one.

The U.S. Army also used the basic ‘Brodie’ pattern up until 1942, when it was superseded by the M1. The M1 Combat Helmet saw action over forty years for the U.S. military from World War II through the Vietnam War.

It was later replaced by the PASGT Helmet, with its nineteen layers of Kevlar and ballistic aramid fabric.

Read another story from us: Weapons That Turned Deadly On Their Own Users

As weaponry becomes more sophisticated, protection for the troops who must manage situational combat also becomes more complex. Perhaps modern body armor deployed in an eighteenth-century battle situation would stand up to the rigors of musket and cannon?

Military planners can better predict today what the needs will be for tomorrow’s soldier. Meanwhile, red coats and livery of all regimental colors have been retained by the military as ceremonial items and as good recruiting tools.