In the years that followed, Antony was busy – he defeated the assassins who had despatched Caesar and later struck up a romance with the queen of Egypt, Cleopatra.

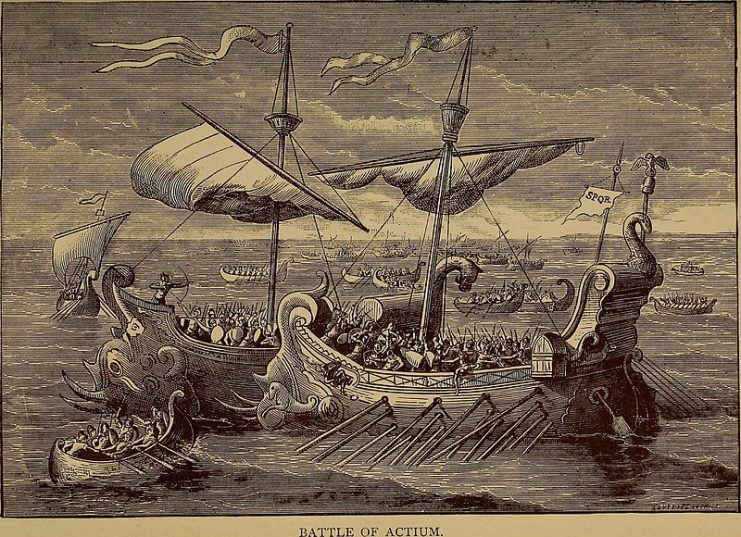

The battle of Actium, which took place off of the west coast of Greece on September 2, 31 BCE, is widely regarded as the decisive moment at which the Roman Republic fell and the Roman Empire rose in its place following the assassination of Julius Caesar.

Octavian, the adopted son and great-nephew of Caesar, faced off against the combined forces of Egypt, led by Cleopatra and Mark Antony who had been a close friend of the late Caesar.

Antony had once been second in command to the emperor. When he discovered a plot against his friend, he was unable to warn Caesar in time and had no choice but to flee Rome. He returned after the coup to try and preserve his friend’s legacy from posthumous attacks by the very men who had conspired to end his life.

Upon learning that Caesar had bequeathed the throne to Octavian, however, Antony contested the younger man’s inheritance. What followed was a decade of ill-fated military campaigns designed to unseat the rightful heir of the deceased dictator.

The forces of Antony and Octavian first clashed the year after Caesar’s passing. Although Antony was soundly beaten, Octavian nevertheless included him and another rival in a power-sharing agreement that divided the Roman empire among them.

In the years that followed, Antony was busy. He defeated the assassins who had despatched Caesar and later struck up a romance with Cleopatra, the queen of Egypt, who had also been Caesar’s lover.

Despite unease among the Romans about Antony and Cleopatra provocatively flaunting their children as royal heirs, the triumvirate ruled steadily for a decade before a series of events led Antony and Octavian to war once again.

Owing to a failed rebellion some time earlier, Antony had been forced to marry Octavian’s sister. When he divorced her in 32 BC, Octavian declared war on Cleopatra – a wise political move which allowed him to cast his war as one fought against foreigners, rather than his fellow Romans.

A year later, having driven Antony’s forces from the Greek mainland, Octavian’s fleet of 500 ships and 70,000 infantry faced off against Antony and Cleopatra’s combined 400 ships and 80,000 infantry.

At first, the battle was uncertain, but upon Cleopatra’s unexpected retreat, Octavian captured much of the opposing fleet and pursued his enemy through the gates of Alexandria.

Naval historians have studied the battle extensively, curious about the effect that Octavian’s smaller ships might have played in ensuring their decisive victory over the comparatively larger ships which made up Antony and Cleopatra’s fleet.

Now, a recent archaeological discovery has helped to shed light on exactly how much of an advantage this gave the Roman commander.

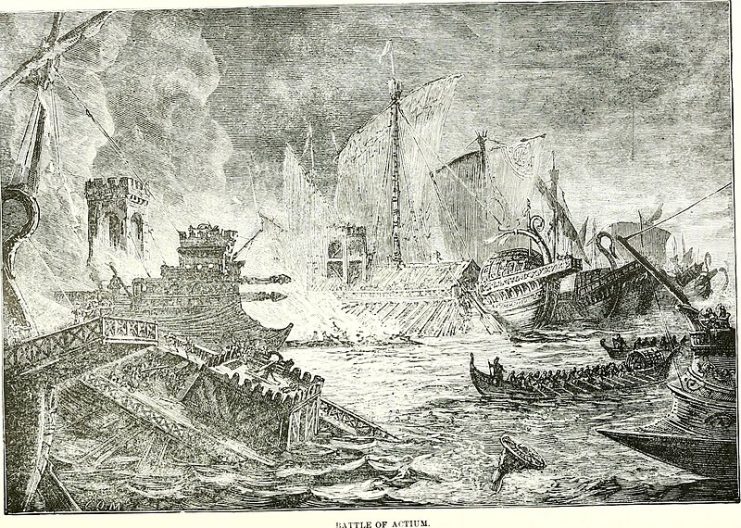

Upon the excavation of Octavian’s monument to the Roman victory (built alongside an entire city devoted to Rome’s success), it was discovered that Octavian took a large number of trophies from the enemy fleet.

The assertion of historians that the larger, less maneuverable fleet was at a significant disadvantage gained some credibility with the discovery that Octavian took as trophies 35 bronze rams from the captured fleet of 350 ships.

The underwater battering rams, designed to break down harbor defenses, were considerably larger than any that had been previously found.

Although only remnants of the rams themselves were discovered in the excavated ruin (it is assumed that later generations or invading forces stole them and melted them down for bronze), the size of the niches they were placed in led historians to estimate that Antony and Cleopatra sailed in ships as large as 40 metres long.

The rams themselves were estimated to be huge, requiring significantly larger supporting timber than was customarily seen in that period.

The greatest among them is said to have been 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) wide, 1.6 meters (5.2 feet) high, and 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) long – dimensions that were previously unthinkable given historians’ knowledge of shipbuilding and naval warfare at the time.

Read another story from us: Ancient Monument Reveals Secrets of History-Changing Battle

Peter Murray, an expert on the subject, acknowledged that “the emerging evidence is likely to revolutionize our understanding of what really powerful marine rams were capable of and help give us a much greater appreciation of the forces behind the resulting collisions.”

Roman engineers were famed for their ingenuity. It is to be hoped that as the excavation continues, more secrets about the battle that spawned the Roman Empire will be revealed to us.