Arguably the most successful espionage ring working in Germany against the Nazis during WWII was code-named “Rote Kapelle” by the Gestapo. This term translates to “Red Orchestra.”

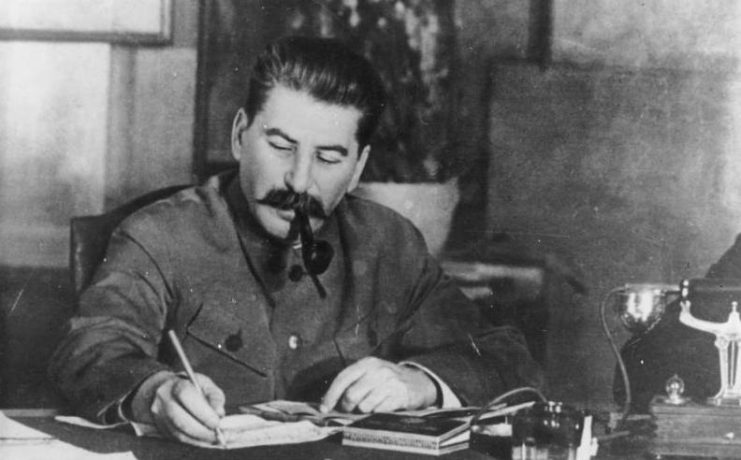

It was such a compelling title that, after the war, Stalin co-opted the name and allowed the Western Allies to build up the Red Orchestra’s deeds to a great extent, knowing they would credit him with its accomplishments.

The Red Orchestra did include communists. Some of them had been involved with the party in the street fighting days before Hitler.

Other members were Social Democrats, members or adherents of the tenets of the former liberal ruling party of Weimar Germany. The rest were somewhere in between.

The members of the Rote Kapelle may have come from intensely different backgrounds, but one thing united them: opposition to Hitler.

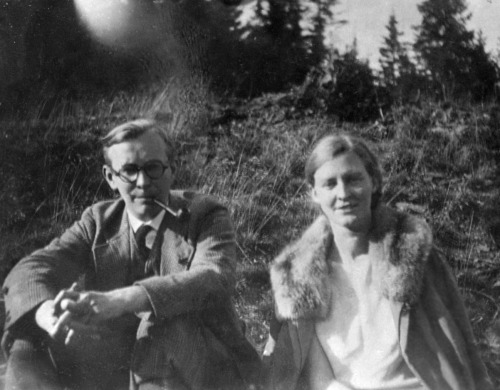

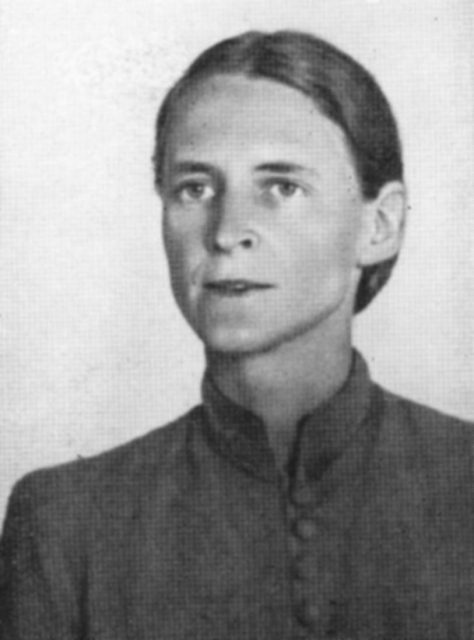

One member of the Red Orchestra was Mildred Harnack (neé Fish). Born in Wisconsin to German immigrants, Mildred became a doctoral student and lecturer on German literature at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

It was there that she met German legal scholar and economist, Arvid Harnack. They soon married. Mildred taught for a year in a college in Baltimore before moving to Germany with her husband in 1929.

Arvid Harnack was from a respected family of teachers, lawyers, and economists. He moved in some elite circles in the Berlin of the early 1930s.

One of his cousins, Hans von Dohnanyi, was a member of the military group that later attempted to kill Hitler.

Arvid was, like many during the Depression, fascinated with the Soviet economic model, which seemed to have avoided a similar catastrophe. Like many others who also sympathized with Soviet communism during that time, he would not live to see what Stalin’s “utopia” was really like.

Arvid gained his doctorate with a thesis which examined American workers’ movements and their migration towards communism. By all accounts, Mildred was like-minded politically.

They joined with about 50 other economists and teachers in forming a study group (like the modern American “think-tank”) on the possibilities of the Soviet planned economy.

The members came from many of the different intellectual elites of Germany: writers, artists, politicians, etc. This group formed just before Hitler’s coming to power and some of the members went to the USSR for a carefully choreographed tour of the country.

When Hitler came to power, the study group necessarily disbanded. Its existence was not strictly illegal, and its members were not members of the Communist Party of Germany, so they escaped the first anti-communist purges that Hitler put into action in 1933.

As it happens, in the first part of the Hitler era, the Harnacks thrived as Arvid gained another law degree and was given a post in the Economic Ministry.

For her part, Mildred worked as a translator and assistant lecturer of the English language and English/American literature. She also became involved with American expatriate organizations. She accompanied her husband on his trip to the USSR, and back to the USA in the later 1930s.

The circles in which the Harnacks moved meant they met several influential people, many of them liberally minded, who hoped for the downfall of Hitler.

The Harnacks formed a discussion group which, among many other topics, discussed and debated the future of Germany and German politics both with and without Hitler. This was a dangerous thing to do, as some of the conversations were decidedly anti-Nazi. They could easily have been turned in.

In 1936, the Harnacks and their group came in contact with Luftwaffe officer, Harro Schulze-Boysen, and his wife, Libertas. The Schulze-Boysens were both from the titled aristocracy and had insight not only into the military but also the aristocracy and the industrial upper classes.

For a time, Libertas worked in the movie division of the Propaganda Ministry and saw first-hand how the Nazis either stretched the truth or simply lied. Harro worked in various positions within the Luftwaffe and had access to many of its secrets, including planning, supply, and development.

In the late 1930s, Harro Schulze-Boysen contacted the Soviets with an offer to send them information, which they gladly accepted. He also tried to reach out the Americans, but their anti-German suspicions prevented them from taking action.

From 1936 onward, the Harnacks were friends with the Schulze-Boysens and others in this growing group. Through Harro and others, Arvid sent the Soviets information regarding the German economy and production.

This group was never “official” in the sense that they had large meetings. That would have been too dangerous. Instead, they met at social occasions and from time to time, one on one.

They were extremely lucky since none of them knew the first thing about spy-craft, beyond a common sense approach.

From the time they began sending information to the Soviets in the late 1930’s until the end, they recruited workers, bureaucrats, and others on the basis of reference and instinct.

Harro Schulze-Boysen and the Harnacks attempted to get information through to both the Western Allies and the Soviets before the war broke out, but only the USSR would listen.

Strangely enough, the longer that the Harnacks had contact with the Soviets, the less they liked them. They still believed in socialism, but the sheen had worn off their ideas of Stalin.

However, they continued to work with him because he was the only one who would listen, even if he had blinkers on sometimes.

The group provided massive amounts of information to the Soviets about the German intention to invade, but this was ignored. When the information ultimately proved true, the German resisters finally found they were being listened to.

Throughout this time, Mildred Harnack’s primary job was to recruit members for the circle. As someone who moved through social, educational, and literary circles, she was in contact with a great many people.

This role took a huge toll on her, and soon she was suffering from extreme anxiety along with the headaches and stomach problems that go with stress.

Throughout 1941 and 1942, the group sent information to the Soviet Union. The Gestapo had been picking up the coded signals of one of the groups’ operators for some time.

In July 1942, they broke the code used by the operator who had stayed on the air far too long too many times. It was at this point that the name “Rote Kapelle” came into play.

Over the next few weeks, the Nazis closed in. In late August and early September, they began to arrest members of the group.

The Schulze-Boysens were arrested on the last day of August and the Harnacks one week later, on the northern German coast where some believe they were attempting to flee to neutral Sweden. Many other members of the group throughout Germany were caught up in the Nazi dragnet.

The Schulze-Boysens and the Harnacks were executed separately during the winter of 1942-43. They were hung at Plötzensee prison on meat-hooks, using piano wire – a most painful and agonizing death. Originally, Mildred was given a six-year sentence, as she played a comparatively lesser role, but Hitler personally intervened and ordered her death.

The bodies were left hanging for days. As the ultimate insult, the bodies were then given to a medical pathologist for experimentation and dissection. No remains or traces were ever found.

Today, the members of the Rote Kapelle are heroes of the Resistance against Hitler. Their lives and deeds are memorialized throughout Germany in statues, street names, and memorials.

Read another story from us: The Rosenbergs: Willing to Die for Communism

Sadly, American Mildred Harnack, along with the other members of the Red Orchestra, fell victim to the Cold War that followed WWII.

They were labeled hard-core communists by the American authorities, even though, by the time they were caught, the Harnacks had both fallen out of love with Soviet communism. American hero, Mildred Harnack, and the others never received the credit they rightly deserved.