Missouri veteran James Rackers may have received his draft notice after World War II officially concluded, but his subsequent military experiences would still carry him to both a historic Missouri military training site and to an overseas city that was decimated less than two years earlier by an atomic bomb that brought an end to the war in the Pacific.

Raised near the community of Taos, Missouri, Rackers finished an eighth-grade education at nearby St. Francis Xavier School and spent the next few years helping his parents work their farm. The war came and went during this period, but the draft finally caught the young man and pulled him from his country surroundings.

“I had gotten a six-month deferment because of the farm work, but they finally got me,” he recalled. “I was inducted into the U.S. Army in December 1945 at Fort Leavenworth [Kansas] and then they sent me to Camp Crowder for training,” he added.

Located near Neosho, Missouri, Camp Crowder is now a Missouri National Guard training site comprising more than 4,300 acres. During WWII, it became a major Signal Corps training site that grew to encompass nearly 43,000 acres and, by some estimates, was home to more than 40,000 troops during the height of the war.

After completing basic training at the southwest Missouri post, Rackers began his Signal Corps training as a lineman, learning to scale poles to hang communications wires. But as his training progressed, he was assigned as a truck driver with the 3247th Signal Base Maintenance Company.

“We were only at [Camp] Crowder for a few months before they said they were going to shut down the camp since the war was over,” said Rackers. “A lot of the barracks there were already sitting empty.”

His company soon transferred to Camp Polk, Louisiana where, Rackers explained, they were told they would be guarding prisoners of war. Instead, they received orders a couple of weeks later that sent them to Fort Dix, New Jersey.

“We weren’t there very long…just long enough to do some machine-gun training, if I remember correctly,” Rackers said. “Then we got orders for Japan and they sent us by bus to Grand Central Station in New York. From there,” he continued, “we took a troop train all the way to Camp Stoneman in California.”

A week after their arrival on the West Coast, Rackers and his fellow soldiers boarded troop ships, then spent the next two weeks en route to Yokohama, Japan, where they were to serve as part of the occupational forces. While aboard the ship, the young soldier recalls becoming “so seasick I thought I was going to die.”

Following his arrival in Japan in November 1946, Rackers was assigned to a U.S. Army camp situated near the base of Camp Fuji. He served as a truck driver and hauled many items, including 50-gallon barrels of heating oil, and lumber used for a specific purpose.

“There was a Japanese man living there who had actually been raised in the United States,” said Rackers. “He owned a sawmill and I would take a team of Japanese workers—many of them former Japanese soldiers—to pick up lumber at the sawmill and to bring it back to the camp.”

The lumber, he went on to explain, was used to crate military equipment for shipment back to the United States. Once the packing was completed, Rackers and his crew would then haul the crates to locations where they would be loaded on waiting ships for final shipment overseas.

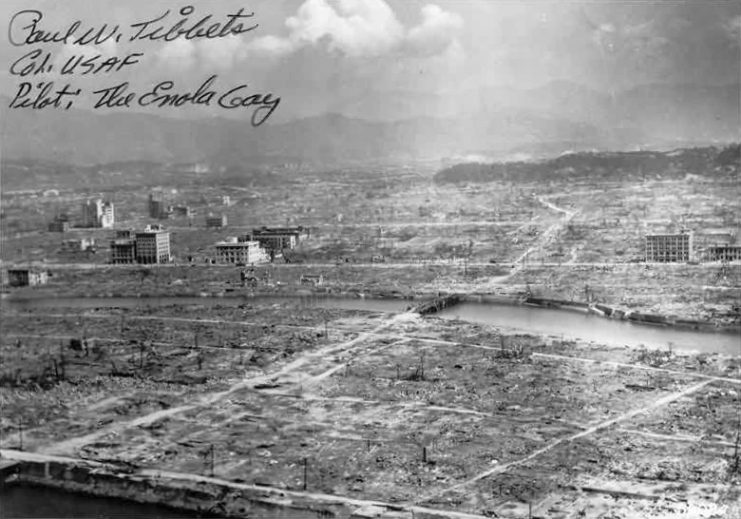

“Our camp was about 20 miles or so from Hiroshima and we were able to visit the area and take photographs,” he said. Little did he realize, the exposure would have lasting effects on his health and that of many of the soldiers with whom he served.

During the summer of 1947, the U.S. Army continued to trim down its force structure since the world was no longer at war. Rackers soon received notice that he would be returning home. In June 1947, he boarded a troop ship bound for Fort Lawton, Washington, and received his discharge from the military on August 6, 1947.

He returned to the farm to help his father and was able to “save enough money to buy a tractor.” In 1951, he married his fiancée, Mardell, and the couple went on to raise four children. Through hard work and perseverance, he and his wife “made a decent living” by running their own farming operations.

Years have passed since his service in the U.S. Army ended, but the consequences of his overseas service emerged as he developed respiratory problems, which are attributed to his exposure to ionizing radiation. Many of his fellow veterans, sadly, have passed away from cancers and other related ailments from service near areas such as Hiroshima.

The veteran is a Life member of the VFW, and served two terms as commander of his local post. When reflecting on his extensive past, Rackers affirms that moments from his brief time in the U.S. Army have never faded and are sculpted into his permanent memories.

“For a farm kid, I got to see a lot of the world and learned a lot of things that I didn’t know when I left home for the Army,” Rackers said. Pausing, he added with a grin, “The one thing I sure do remember quite clearly is they didn’t pay us a whole heck of a lot back then.

Jeremy P. Ämick is a military historian and author of several military history books available at MissouriAtWar.

“I made a dollar a day, that’s all I got. But it was all a valuable experience.”