Throughout human history men have gone to war. Naval transport has created and broken empires, but the harshness of nature means sometimes those traveling by sea do not make it to their intended port. This was as true during the height of the Roman Empire as it was during the fall of the Third Reich.

In 1943 the war started to turn against the Axis Powers. The Soviets rallied and prepared to swarm the Reich by the hundreds of thousands. In the West the British, Commonwealth nations, and Americans prepared to launch an invasion of Nazi-held Europe.

In the south, Fascist Italy had fallen, and the rebuilt Italian government was now an ally against the Reich. Hitler’s Nazi regime still held parts of Italy and large swaths of Greece.

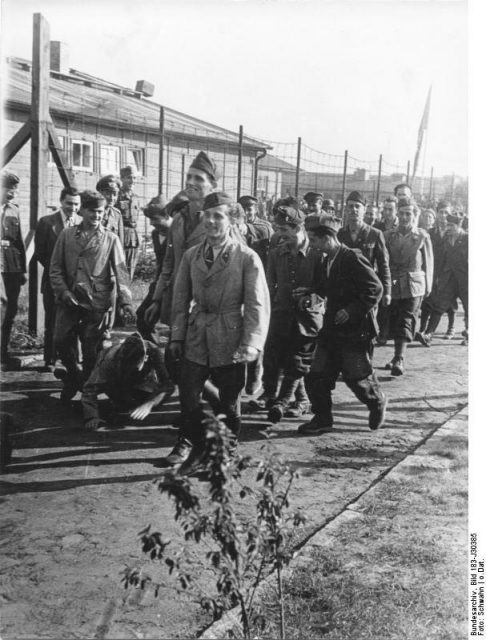

Along with those lands came thousands of prisoners of war (POWs). With the Reich on the defensive, many in the regime questioned what to do with them.

The Italian prisoners were given a choice to join the Reich or remain prisoners. The Italians, disillusioned with fascism, refused to fight for the Reich.

Concerned that if the numerous prisoners rebelled they would present a threat, the Nazi commander in what remained of Fascist Italy and Greece readied the relocation of the POW’s to where they would not pose a threat. After being held on several Greek islands in the Mediterranean, the prisoners were boarded onto merchant ships for eventual transport to Germany.

All told, roughly ten thousand Italian prisoners of war were packed like sardines into appropriated merchant vessels. Less than 500 of the POWs made it to Germany.

Most succumbed to Allied fire during the Battle of Rhodes, in which British naval forces fought what remained of the Italian Fascist regime’s maritime fleet in the Mediterranean. As most of that fleet were merchant vessels, the British came out ahead in the conflict.

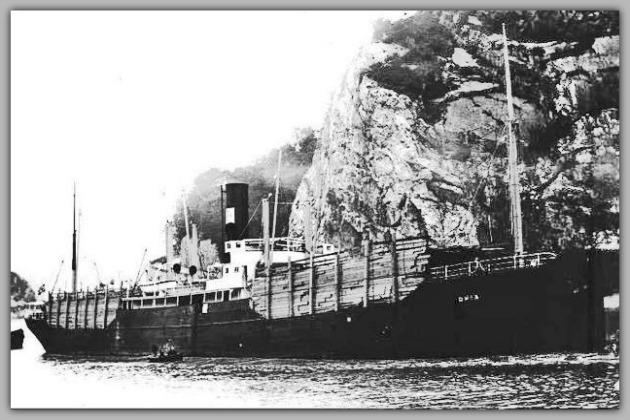

The merchant vessel Oria, loaded with over 4,000 prisoners in June 1944, suffered a different fate.

En route from the Dodecanese Islands to Piraeus, Greece, the vessel ran aground. A navigational error during a storm caused Oria to hit the island of Gaidouronissi. The ship promptly sank. Of the over 4,000 prisoners on board, only 27 survived.

One of the survivors remarked that he managed to live because “After the impact of the Oria against the rock I was thrown to the ground and when I could get up a strong wave pushed me into a little room in the bow of the ship, on the same floor of the deck.”

Eventually finding a rent in the hull, the handful of survivors reached the exposed prow of the ship. From there, they managed to signal an Italian tugboat for help.

Although the Nazis in charge of the Italian prisoners were tried and convicted for the mistreatment of the POWs, the wreck lay forgotten on the bottom of the Mediterranean. It would lay undisturbed for nearly sixty years.

The wreck’s discoverer, a Greek diver and historian by the name of Aristotelis Zervoudis, found it in 1999 thanks to advice from local fishermen. It took several dives to confirm that the wreck was indeed the downed merchant vessel. In 2002, the wreck pointed out by locals was confirmed as SS Oria.

Read another story from us: The Invasion of Cos: The Killing of 103 Royal Italian Army Officers

Further research through Red Cross records revealed the list of POWs aboard the vessel. Thanks to Zervoudis’ research, the families of the Italians who died in the ship’s sinking finally received the closure long denied them by Nazi brutality and post-war recovery.

The wreck serves as a monument to those who rejected Nazi control of their homelands and paid for their defiance.