The Victoria Cross (VC) is Britain’s highest award for military valor. Before 1911, Indian soldiers were not eligible to receive it; although many deserved to.

Fazal Din was born on July 1, 1921, in Hoshiarpur, East Punjab, British India. He was a member of the Jaat people who are traditionally low-caste farmers. The sub-caste Din belonged to were Muslim, not Hindu. They are allowed to fight; as many have with history-changing results.

At the outbreak of WWII in 1939, Din joined the British Indian Army as a rifleman and became a section gunner in the 10th Baluch Regiment (now part of the Pakistan Army).

In January 1942, Japan invaded Burma, but they did not do it alone. They had help from Thailand, the Burmese Independence Army, and the Indian National Army (INA). The last two were anti-British forces who hoped that Japan would liberate their countries from British rule. The Burmese got their wish, but not in the way they expected.

The invasion was successful; driving the British out of Burma and back into British India. By 1944, the Japanese felt secure in their grip as they had widespread support from the Burmese. They prepared for the next phase of their empire building by following the British.

They called it Operation U-Go; the invasion of British India. Due to the INA, Japan’s leadership were convinced that most Indians would prefer a “partnership” with Japan instead of continued British rule. On their part, the INA believed Japan would give India its independence. Both were wrong.

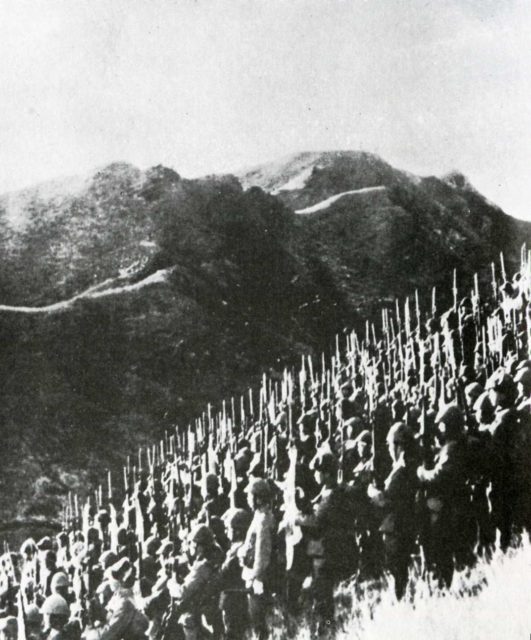

U-Go failed spectacularly. British, American, and Chinese forces drove the invaders back then followed them into Burma in November 1944. To make matters worse, the Burmese realized the Japanese were not the saviors they had hoped for. It resulted in a surge of anti-Japanese sentiment and resistance movements.

Outnumbered, besieged on all sides, low on supplies, and with poorly-equipped, hastily-trained recruits from Japan, the tide began to turn. By January 1945 the Japanese were fighting a defensive war. Anticipating a major Allied assault on their stronghold in Mandalay, they dug in.

The British were expecting just that, however, so they made their way to Meiktila, instead. That city was a major stopover for supplies of food and ammo destined for Japanese forces in central and northern Burma. If they could take it, they would choke off most of the country, thereby securing an Allied victory. Or so they hoped.

To fool the Japanese, the Indian 33rd Corps were dispatched to Mandalay. The Japanese fell for it and began nightly attacks on the 33rd. While they did so, several British Indian Army divisions headed toward Meiktila.

The attack commenced on February 29, led by the Indian 17th Division. They took the airfield at Thabutkon (some 20 miles west of the city), thus keeping the Japanese out of the skies. The city itself was defended mostly by members of the 168th Regiment of the Japanese 49th Division; about 4,000 men.

Not all of them were in Meiktila. Many were heavily entrenched in bunkers, machine-gun and sniper’s nests, as well as anti-tank positions around the city. Most of them were ready to die for their emperor. If the Allies failed to kill them, they would kill themselves. What they had not counted on was someone like Din.

Din, by then, was a Naik (the equivalent of a corporal) in charge of the 7th Battalion of the 10th Baluch Regiment. The attack on the city began on March 1 and did not go well for the Japanese.

Although well-positioned, many lacked heavy equipment, especially anti-tank weapons. To compensate, some Japanese soldiers strapped bombs on themselves then ran toward the oncoming tanks. Most did not make it as they were shot before they got anywhere near.

The following day, Din led an attack on a bunker position. It had repelled an earlier assault, killing many of his friends. To provide support, a tank went ahead of them, but it continued moving forward, leaving his unit exposed.

To one side of their group was a set of three bunkers. On the other was yet another bunker beside a house. They were trapped. Gunfire cut his men down like wheat.

Rushing toward the three bunkers, Din attacked the one nearest him; destroying it with grenades. The other two lay silent because they were empty. He wheeled toward the last bunker as bullets mowed more men down, but not Din.

Then the shooting stopped; the Japanese had run out of ammo.

Furious, eight soldiers burst out of the house, wielding swords. The two in front were officers, screaming as they made a beeline toward the Indians.

A Bren light machine gun killed one of the officers and a soldier but in doing so he, too, ran out of bullets.

He was immediately killed by the second Japanese officer’s katana. Din ran to help, but the sword whooshed again – skewering him through the chest. Its tip kept going until it poked out through his back. It took the other Indian soldiers a while to realize what they were seeing.

Satisfied, the Japanese officer withdrew his sword to launch another attack. Before he could do so, Din snatched the sword from his hand and slashed at him; killing the second officer.

He then rushed to help another soldier who was desperately trying to fend off a sword attack. Another slash, another dead Japanese. Waving the sword, he ordered his men to keep fighting until they had finished off everyone else in the house.

He then walked 25 yards to give his report to Platoon headquarters; still with a hole through his chest. He collapsed, of course. He was taken to the Regimental Aid Post, but he did not survive.

The following day, Meiktila was in Allied hands, and on May 24 Din was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.