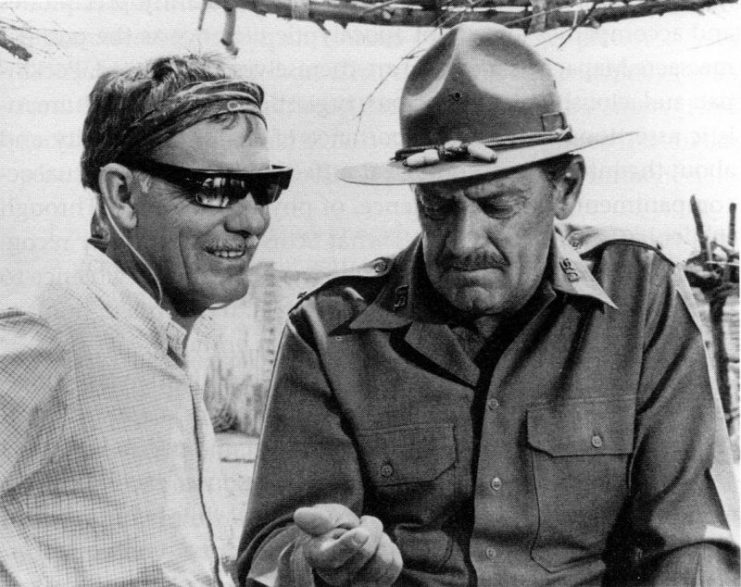

Sam Peckinpah and the making of The Wild Bunch

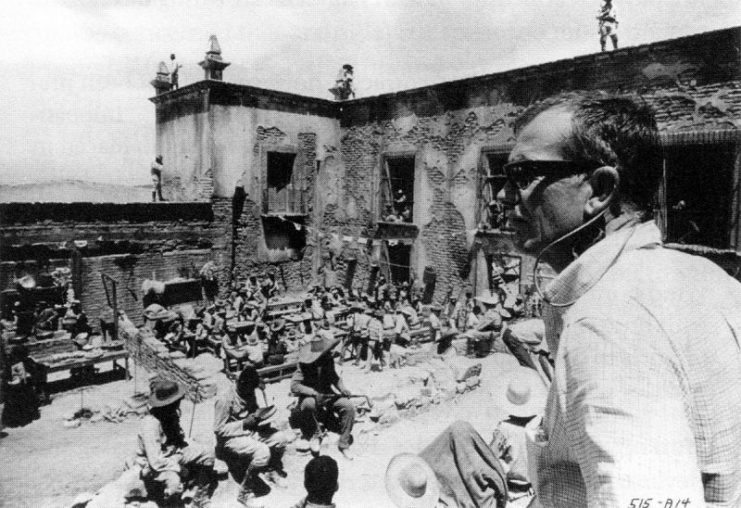

A little more than 50 years ago, director Sam Peckinpah was looking forward to making a western, The Diamond Story, with Lee Marvin who was a huge box office star at the time.

Then, Marvin abruptly changed his mind and went off to make the musical western Paint Your Wagon with Clint Eastwood instead.

Peckinpah was left without a project, and that’s when he heard about a script written not by a professional screenwriter but by a movie stuntman, Roy Sickner.

Peckinpah read the script, liked it and set out to make what has been called “one of the great masterpieces of modern cinema.” It also happens to be among the best action movies you’re ever likely to see.

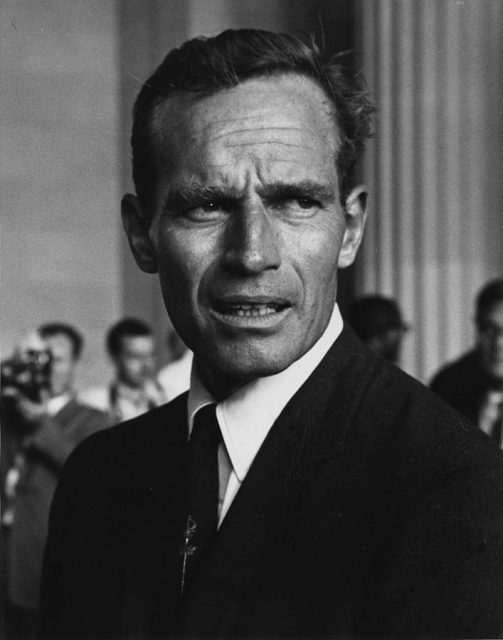

Professionally, Peckinpah wasn’t in a good place in the late 1960s. In 1965, he had completed what he believed was his best film to date, Major Dundee, a story set in Mexico about an obsessed, driven cavalry commander, wonderfully played by Charlton Heston.

The studio took a look at the 160-minute long final cut and disagreed. They didn’t even bother with previews – instead they brutally cut the film before release, removing most of the violence which Peckinpah believed was intrinsic to the story. Peckinpah was actually barred from the editing room during this process and then abruptly fired.

After that, Peckinpah was effectively blacklisted in Hollywood, and he worked in television for a time before Warner studios relented and offered him the opportunity to direct the Lee Marvin western. When that fell through, Peckinpah persuaded them to back a new project based on the screenplay by Roy Sickner. The movie was to be called The Wild Bunch.

Like many movies that had gone before, The Wild Bunch was about a group of outlaws. But that was where the similarities ended.

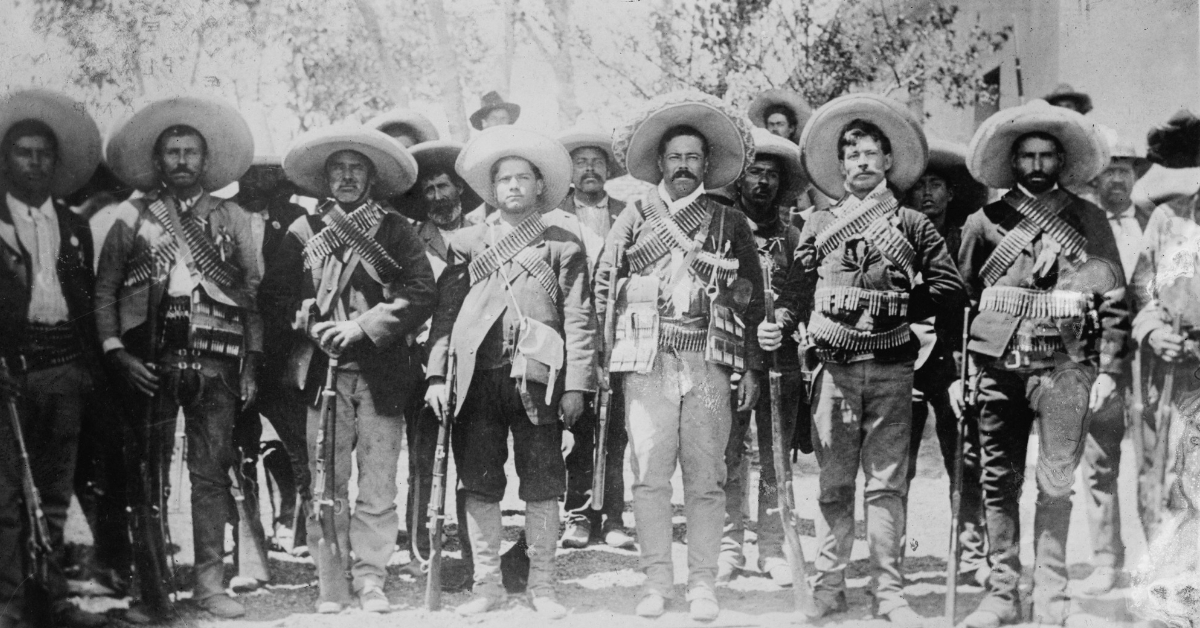

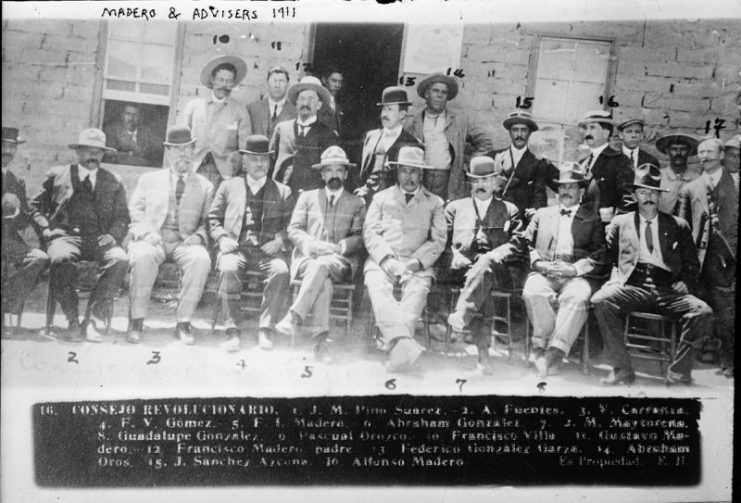

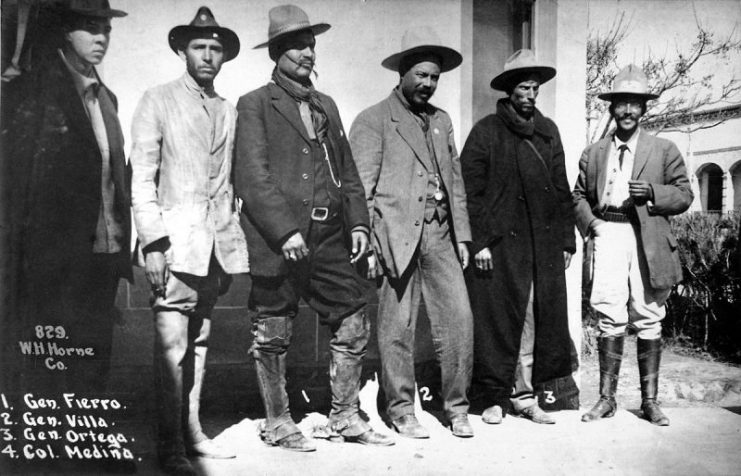

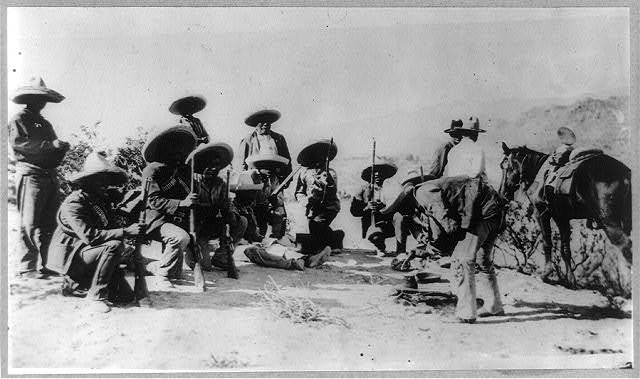

The film was set during the Mexican Revolution, and Peckinpah was determined that it should be as authentic as possible. It was to be filmed on location in Mexico and should reflect the casual brutality of the revolution.

The script included lots of Mexican characters and Peckinpah insisted that these should be played by Mexican actors. That may not seem strange now, but in 1969 it was a radical approach for a Hollywood movie.

When Orson Wells had made A Touch Of Evil just ten years earlier, no-one would countenance the main character, a Mexican policeman, being played by a Mexican actor. So the role was given to Charlton Heston who was provided with laughable “blackface“ make-up.

The other thing that Peckinpah was concerned about was guns. He was a keen shooter and an ex-Marine, so he knew his way around firearms. He was disgusted with the way that guns and shooting were portrayed in the films of the mid-sixties.

Whether it was war films or westerns, all the guns sounded the same, and when someone got shot, they generally just collapsed bloodlessly to the ground or tied a handkerchief round the afflicted part and carried on. Peckinpah wanted the guns and the effects of being shot to look real in this movie. He said:

“We wanted to show violence in real terms. Dying is not fun and games. Movies make it look so detached.”

The Wild Bunch was accused of many things, but never detachment. Stunt arrangers showed Peckinpah “squibs,” small capsules of blood which could be exploded to simulate the effect of a gunshot wound to the human body. They detonated several of these on card cut-outs propped against a fence.

Peckinpah wasn’t impressed. He produced a large-caliber handgun and blasted holes in the targets. “That’s what I want!” he told those nervously watching.

The special effects crew went off and designed bigger squibs, loaded with fake blood and meat and coupled these to a larger explosive charge. They tried that. It was better, but Peckinpah still wasn’t entirely satisfied – the blood, he said, was too red and unrealistic.

The blood was darkened, but the director still wasn’t happy – the guns didn’t sound right because they were firing blanks loaded with small charges. The amount of powder in the blanks was increased until Peckinpah finally seemed to be content.

Then the crew prepared the blank ammunition for the actual filming. It amounted to 90,000 rounds in all, which is more ammunition than was expended during the actual Mexican Revolution.

The guns used in this movie were carefully chosen by Peckinpah to be in keeping with the period. It’s set in around 1912/13 and the outlaws, who spend some time disguised as US soldiers, carry the new (at the time) Colt M1911 in addition to revolvers.

However, in some shots it’s obvious that they are using Astra Star Model B pistols, a later Spanish copy of the Colt 1911 which is recognizable by its external extractor and apparently works better with blanks.

There are also Colt Single Action revolvers, Winchester Model 1892s, Springfield M1903A3 rifles, and even a couple of Lugers. All were completely in keeping with the time in which the movie is set.

In fact, there is only one real firearm anachronism in the whole film, and that’s the water-cooled, tripod-mounted machine gun which appears in the final shootout. It’s clearly a Browning M1917 which wasn’t around until several years later.

The outcome of all this care and attention was a film which scandalized and horrified many people when it was released in 1969 – “pure wasted insanity” was the comment of one viewer at an early screening. Cinema-goers just weren’t prepared for this level of violence. The final shootout alone involves more than 100 screen deaths in a little over four minutes.

But audiences also weren’t prepared for protagonists who were really, deeply unpleasant. The members of the outlaw gang in this film have a Samurai-like code of personal honor, but this applies only to themselves.

Near the beginning of the story, the gang takes hostages, including a woman, during a bank robbery. William Holden tells one of the gang, who is covering the hostages with a shotgun, “If they move, kill ’em!” They move. They are brutally executed.

To audiences of the time, this just wasn’t how cowboys were supposed to behave.

The film isn’t just about violence. There are long stretches when the main characters do little but talk to one another, mainly ruminating on the fact that growing old means that they find themselves in a world in which they have no place, a world in which honor and self-respect seem to have been abandoned.

However, it is the violence which remains in the memory long after the final credits have rolled.

The real Mexican Revolution was a bloody affair. It wasn’t so much a single revolution as a series of coups and counter-coups which ravaged Mexico from 1910-1920 and left up to 2,000,000 people dead.

Real violent death is seldom pretty or bloodless, and Peckinpah’s insistence on realism means that The Wild Bunch portrays this as accurately as 1960s special effects allow. We feel for the protagonists, despite some of the evil things that they do, partly because the potential violent death they face looks so painful and unpleasant. Just as it really is.

It wasn’t just moviegoers who were horrified by this film. In 1969, 20th Century Fox were also planning to release a big-budget movie, but something very different to the gritty realism of The Wild Bunch.

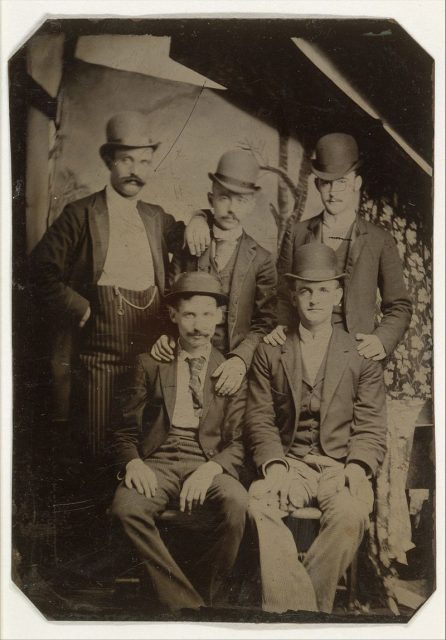

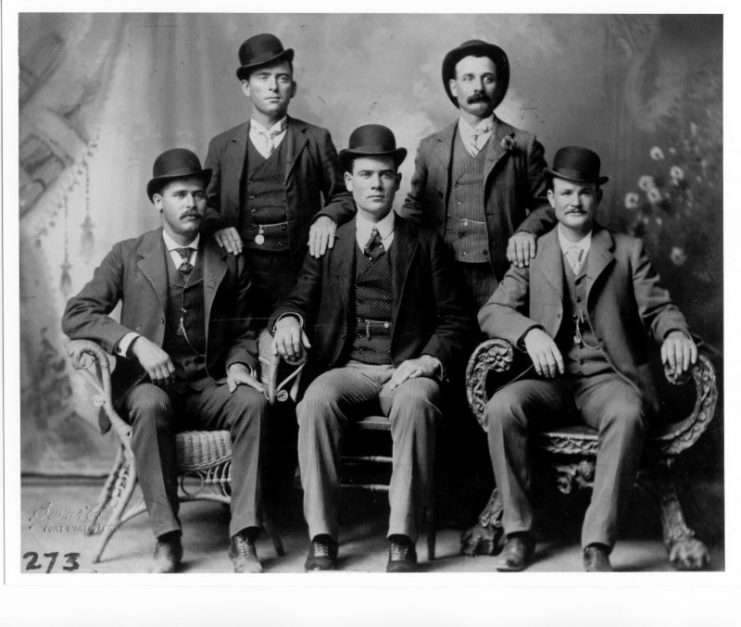

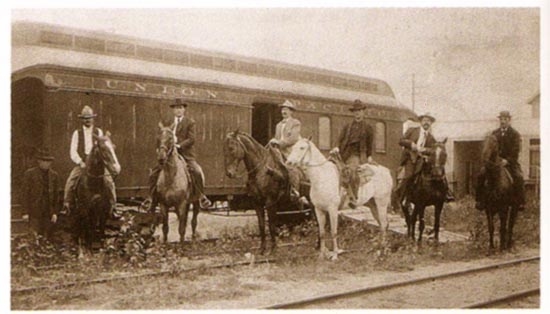

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was a feel-good western about a pair of men who were, despite being outlaws, all round nice guys.

In real life, Butch Cassidy’s outlaw band was called the Wild Bunch. But no-one at 20th Century Fox wanted to risk audiences making a connection between the wholesome family entertainment of Butch and Sundance and the nastiness of Peckinpah’s movie. So Butch’s gang was hastily re-named the Hole-in-the-Wall gang.

It’s difficult to classify The Wild Bunch. It certainly isn’t a traditional Western, but then it isn’t entirely a war film either. Calling it an action movie probably does it a disservice – it’s much, much more thoughtful, intelligent, and melancholy than the vast majority of action movies.

I suppose that it’s unique, and perhaps that what makes it so significant. The Wild Bunch certainly changed the way that audiences thought about violent on-screen death.

The sanitized deaths that had been a staple of war movies and westerns up to that point suddenly weren’t satisfying. Most movies which followed began to switch to a more realistic portrayal of violent death.

Even today, there are still arguments about whether this approach ends up glorifying violence or whether portraying it accurately prevents people from acting out violently.

The one thing The Wild Bunch is short on is laughs, but if you look carefully, the title sequence does include one shot that may make you smile.

Peckinpah famously fell out during filming with actor Robert Ryan, who demanded top billing. Ryan was certainly the most experienced actor on set and a former Hollywood leading man, but Peckinpah insisted that top billing went to William Holden and Ernest Borgnine.

In the opening sequence, as the outlaws ride into town, the screen freezes on a shot of William Holden’s face, and his name appears on the screen. Then, it does the same with Ernest Borgnine. Immediately after, the screen freezes on a shot of the rear ends of horses, and Robert Ryan’s name appears on the screen.