With few other ports offering facilities able to cope with such massive vessels, the American Navy got creative in its solutions.

When the United States of America entered World War II, the nation faced a slew of logistical problems unique to each theater. From the sands of Vichy-occupied Africa to the hedgerows of France, American soldiers fought a largely conventional modern war as envisioned by strategists. The Pacific Theater would prove a very different campaign.

The forces mustered against the Empire of Japan in the Pacific faced a host of difficulties, the most obvious being the need for a lengthy logistical train for their forward units.

Though the modern technology of the time mitigated those problems to some extent, the sheer scale of the campaign in terms of mileage created difficulties for all parts of the American military. Troops traveled long distances even as they hopped from island to island to force back the Japanese.

In addition, airplanes needed outposts and aircraft carriers to land, refuel, and rearm. Pivotal to all this was the need to keep the Navy supplied, armed, and afloat.

Repairing and refitting the large carriers, cruisers, and battleships deployed in the Pacific required sizeable drydock installations. Though the drydocks in Pearl Harbor were repaired and useable during the war, their distance from the campaign theater meant ships requiring repairs had a long way to go.

With few other ports offering facilities able to cope with such massive vessels, the American Navy got creative in its solutions.

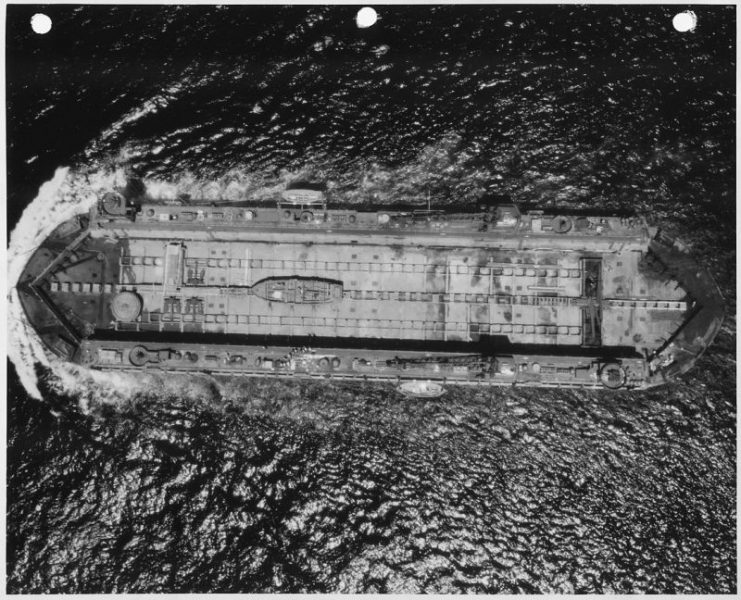

The Navy’s solution was portable floating drydocks. Officially designated Advance Base Sectional Docks (ABSD), the moveable docks consisted of large pieces welded together to allow repairs at sea or in those instances where proper repair and refit facilities didn’t exist at a nearby port.

The ABSDs came in two sizes. The smaller of the two, combined from eight sections welded together, could support a ship of up to 8,000 tons in weight, 120 feet wide, and 725 feet long. The larger docks were built from ten sections and could hold a ship up to 90,000 tons.

Despite being top heavy, the docks could be safely (though slowly) towed thanks to clever construction and foldable walls. They included cranes with a 15-ton lift limit, crew housing, and diesel generators.

By the war’s end, four small docks and three large docks were completed and in service. The first dock entered use in 1943, with the others quickly following.

The drydocks proved their worth countless times, allowing repairs and refits much closer to the campaign theater and allowing vessels too damaged to make their way eastward a chance to continue the fight. From destroyers and troops ships to battleships and aircraft carriers, the ABSDs kept the United States Navy operational and pressing forward against the Japanese.

Even with the war’s end, their service continued. ABSD-1, the first of the massive floating drydocks in use, continued intermittent service for decades after World War II. Parts of it were decommissioned, scrapped, and utilized throughout the latter half of the twentieth century.

It even continued supporting the Navy in some small way as parts of it served as a drydock during the Korean Conflict. The last piece in service was decommissioned in 1998.

The portable drydocks were an answer to the problem of a far-flung navy fighting a regional naval power without having to send its forces long distances for repairs or having to scuttle vessels too badly damaged to make the journey. Thanks to the floating drydocks, the United States Navy managed to keep pressing the advance as they forced the Japanese back island by island.

Read another story from us: Mighty MO – USS Missouri (BB-63) Video and Photos

Even after the war, they continued to aid the Navy and bridge the logistical gap between the American homeland and the far-flung theaters of the Cold War. Thanks to their use and American ingenuity, the brutality of the Pacific Theater ended all the more quickly.