Our story begins about midnight at Old Buckenham Airfield, England, in the spring of 1944. Despite the propensity and value of nearly boundless technology and information at our fingertips, solving life’s most pressing problems sometimes requires decisively bold action right now.

The author is retired USAF test pilot, Colonel Bill Norris, who began his flying career as a 22-year old second lieutenant in WWII. The context for this vignette is that his ten-man crew is flying as lead B-24 for a squadron on a 11+ hour combat mission. Confronted with a problem for which there was no conventional solution, the crew had to think (and work) outside the box to make it through in one piece.

In his own words:

“We were alerted for a mission and the usual procedure was for the crew to pre-flight the B‑24 and munitions load prior to mission preparation and briefing. As Squadron lead, our Navigator and Bombardier prepared the route & target folders while I worked with Operations on the departure, formation and in‑flight procedures.

Our Group of 26 B-24s — each loaded with (4) 2000lb bombs — was to join hundreds of other bombers and fighters from the Eight Air Force on the mission. Our aircraft’s load included a couple of 100 lb smoke bombs because — as lead — our formation dropped on our release and the smoke bombs acted as a marker.

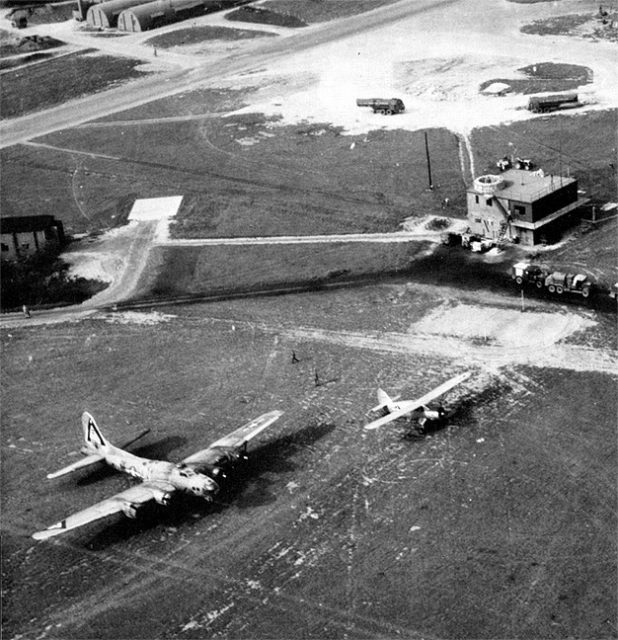

All was well until our crew chief found an engine problem that couldn’t be fixed in time for take‑off. Therefore, we had to use a backup aircraft. Time was moving rapidly toward mission take‑off time and we had a new bird to preflight. We immediately encountered a problem in that the spare’s bomb load wasn’t correct and had to be downloaded and replaced in the dark and rain well before sunrise.

Adding even more to the degree of difficulty was the fact that the spare B‑24 had several major differences from our “H” model including the cockpit layout, flight controls. defensive weaponry and the bomb sight. But there was one particular difference between it and our normal aircraft that was about to bite us in the keester: the two birds had different locations for the pitot-static system which provide the pilots with airspeed, altitude and rate of climb/descent.

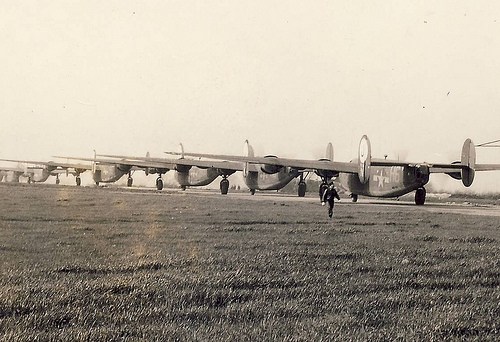

The download/upload of bombs took darn near every bit of the time remaining and we were pressed to man-up, crank up the four engines and get to the runway to lead the takeoff sequence. As usual, the weather was lousy. A ragged 600 foot ceiling, moderate rain and solid clouds from 18oo to 20,000 feet.

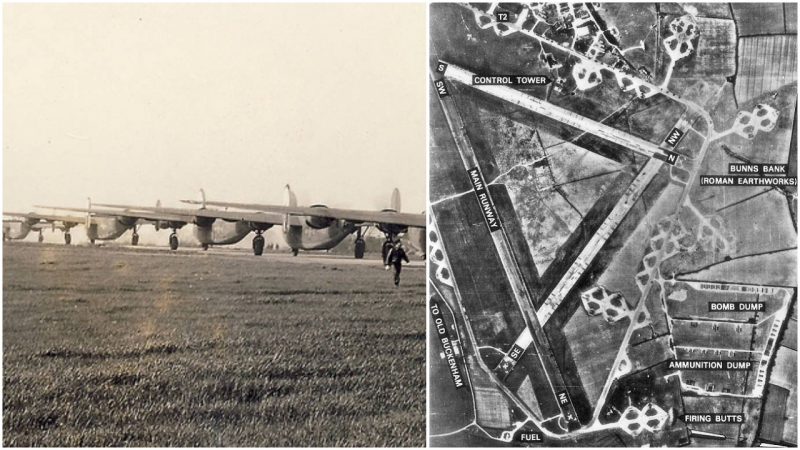

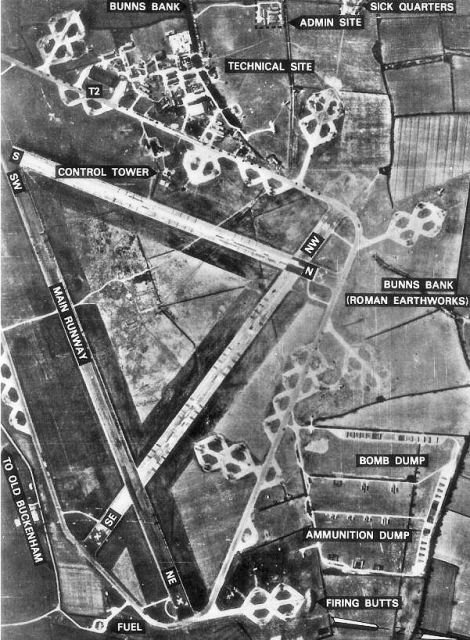

We had specified climb corridors and routes since there were several nearby bomber and fighter groups executing similar departures. The plan was for each of the 25 B-24’s following us from Old Buc to penetrate the clouds individually and — once on top — rendezvous with us via the Buncher 6 radio beacon.

We would then join with other groups to form the Division as we departed the English coast for Germany. By that time it would be daylight and we knew German flak would begin right away— prior to crossing the coast inland — from flak barges and would continue in varying intensity and accuracy until we re-crossed the Channel on the way home.

For example, one battery at Abbeville always scored hits, while others could not seem to hit anything. When not in the midst of flak, we’d be under attack by Luftwaffe fighters. The boys out of Abbeville earned a reputation for being especially deadly.

We took the runway with the deputy-lead on the right wing. I applied power and we rolled slowly down the runway, heavy with full fuel and the bomb load. I eased the B‑24 off the ground and called for the gear retraction.

Checking the instruments, I found – with some trepidation – that we had no airspeed, erratic rate of climb and questionable altitude. There was no choice but to proceed and soon we were mired in thick cloud and rain.

Fortunately, the aircraft was flying well and we were climbing at a positive — if unknown — rate. Without the gauges we rely upon in zero visibility, I had no choice but to fly the aircraft by attitude, power and the seat of my pants. We needed to unscrew this ASAP, so I called for Chris (our flight engineer) to make his way up to the cockpit and explained the situation

Given that our pitot-static system was totally defunct, we ran through the possibilities and quickly diagnosed the problem. In our hasty departure, the protective covers had to have been left on the tubes shutting off both the ram and static “air” sources needed by our gauges.

Problem was — even though we understood what went wrong— we still had to solve it because we needed both airspeed and altitude for bombing, to say nothing about normal flying and recovery, assuming we got home in one piece.

Running out of the proverbial airspeed, altitude and ideas, our solution was a bit drastic, but none other came to mind. As I kept us climbing wings level, Chris got his tool box, went up to the bombardier’s compartment and chiseled out a sizable hole in the side of the fuselage just ahead of where he knew the left-hand pitot tube to be.

He then reached out and pulled the cover off the pitot tube and — like magic — we had airspeed, altitude and rate of climb for the rest of the mission.”

One might wonder how the Air Force reacted to a major chunk missing from the aircraft upon return. When I asked, Dad laughed and said:

“Oh that? Not an issue. The hole was easily explained as battle damage since we had collected multiple holes from heavy flack and German fighters (ME‑109 20mm ammunition). But, to my knowledge, this specific bit of mission information never made it into the debriefing folder; an unintentional oversight I’m sure…”

Asked what lesson he and the crew gleaned from the experience, Dad shared this nugget:

Let’s just say, we re-learned one of the basics taught to every aviator before or since:

___________________________________________________________________________________

Robert Norris.

Author & Historian.