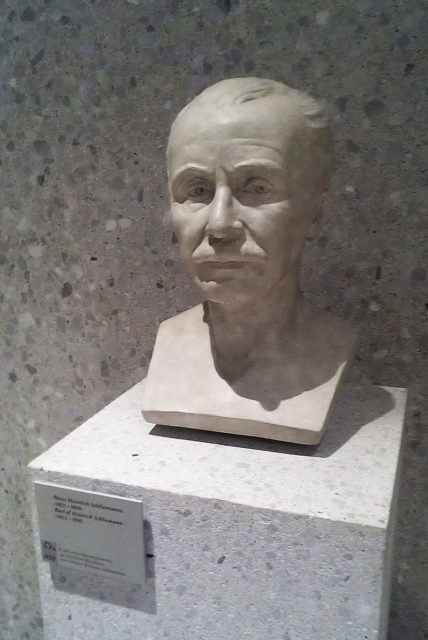

It’s difficult to mention either the early days of archaeology, Troy or even the history of ancient Greece without mentioning Heinrich Schliemann.

The German archaeologist, born 1822, also helped to further the idea that perhaps Homer’s works were really based on actual historical events that occurred, rather than being just fiction.

The Beginning

Schliemann was obsessed with finding the location of Troy, with his interested peaked early in his life by Homer’s works. In fact, he even went so far as to say that, as an eight-year-old, he claimed he would find the city of Troy. Of course, who’s to say if this actually occurred, as it could have been a mere way for Schliemann to draw the public eye to his story.

It also conflicts with another tale Schliemann told regarding his past, saying his first interest in the Homeric works didn’t even come about until he was in his teen years, and he overheard an intoxicated man recite some Homeric verse in the grocery store where he worked.

Schliemann had a bad habit of spinning tall tales regarding his life, and told stories about witnessing the San Francisco Fire and dining with President Millard Fillmore in Washington, D.C. However, it’s highly doubtful that either of these things happened.

From Rags To Riches

Regardless of what the true stories might be, Schliemann’s lack of a formal college education actually helped steer his life onto the path that would eventually lead him to Troy. Because of a lack of funds, his father could not afford to give the young Schliemann a formal education. Because of this, he was forced to take odd jobs here and there around Europe.

He eventually landed on a job with an importing and exporting firm that allowed him to travel quite a bit. During his travels, he showed a remarkable aptitude for learning languages, and could eventually speak not only German, but also English, French, Italian, Swedish, Spanish, Polish, Portuguese, Dutch, Russian, Turkish, Arabic, Greek and Latin.

His travels also allowed him to further his education in his own way. He learned quite a lot of business savvy, and ended up making a good deal of money off the California Gold Rush, which enabled him to begin a life as a gentleman. He retired at 36 and, at this point, was fully obsessed with Troy. He announced his dedication to finding the city, divorced his wife and moved to Athens.

The Right Spot

Up until this point, the location of Troy was a bit of a gamble. Some didn’t even believe the city existed at all, accounting it all to fiction. However, there was the population of believers who kept the search alive. About 40 years before Schliemann arrived on the scene, a Scottish journalist picked a spot that he thought would hold the lost city.

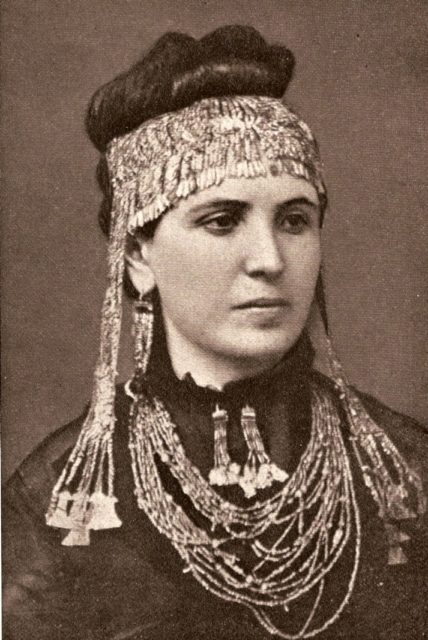

The land was later owned by an American man living in the region, and it was this man that Schliemann approached in order to conduct an extensive excavation on the area. Before beginning excavation, though, Schliemann would need a new assistant. What better way to find one than by advertising for a wife in an Athenian newspaper? He met a young woman 30 years younger thanhim,named Sophia.

The Jewels of Helen

Excavations began in 1871. Assuming that the Troy Homer refers to must be in the very lowest portion of the hill he was excavating, Schliemann immediately dug through all of the upper levels to get to the bottom, possibly missing quite a lot of artifacts. In fact, he has been criticized greatly for using dynamite for this purpose, potentially destroying important historical pieces. However, two years later in 1873, he came across what is now known as Priam’s Treasure and the Jewels of Helen.

He originally said that he and Sophia excavated the brilliant gold ornaments by themselves, alone, and carried off the gold in Sophia’s shawl. He later retracted the story, though, and said it was a lie. Sophia, did, though, wear the jewels in public at a later date.

Later, these same jewels found a home at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, but were stolen by the Soviet Army during World War II, and now reside in Moscow.

Stealing and Smuggling

Finding the gold and jewels was only the beginning of a line of drama, though. Schliemann published his findings in a paper entitled “Trojan Antiques,” which the Turkish government read and then sued him over, as he had been digging on a side of the hill that stretched over into Turkey.

However, he smuggled the gold out of the country, refusing to let government officials get their hands on his findings. Turkey, however, made sure that he did not dig in the same place again for the next two years.

The Mona Lisa of Prehistory

However, satisfied with finding what he felt was sufficient evidence of the location of Troy, Schliemann turned his attention to excavation at Mycenae, another ancient Greek location. There, he made a great discovery – royal grave shafts, along with all their treasures. He even claimed to discover the skull of Agamemnon, a Greek legend in mythology.

Whether or not the skull actually is that of Grecian leader, the golden mask adoring the skull became quite famous and is sometimes called the Mona Lisa of prehistory. You can see it at the National Archaeology Museum of Athens.

A Great Life

Despite his habit for stretching the truth and just outright lying on occasion, along with his blatant disregard for following the rules, especially when he wanted to excavate somewhere he didn’t quite have permission, Schliemann can still be admired for his utter tenacity.

His great belief in the ancient city of Troy led him on a remarkable journey that resulted in the discovery of some of the most important artifacts of his time. Schliemann died in 1890, rather ridiculously, from what started as an ear infection, then resulted in a coma. He is buried in Athens, in a mausoleum designed after ancient Grecian architecture.