In May 1940, Nazi Germany invaded France. The resulting campaign was a disaster for the Allies. The Germans tore through north-east France, completely outmaneuvered their opponents, and knocked one Europe’s great powers out of the war in just over a month.

How did it go so wrong?

The Defensive Plan

The forces defending France were impressive. At the start of the war in September 1939, the country had 800,000 men under arms. More were quickly raised, so that by May 1940, 94 French and 10 British divisions stood ready to repel the Germans.

When the Germans invaded Belgium on the way to France, 22 Belgian divisions joined them. The French alone had more tanks than the Germans: 3,254 against 2,574.

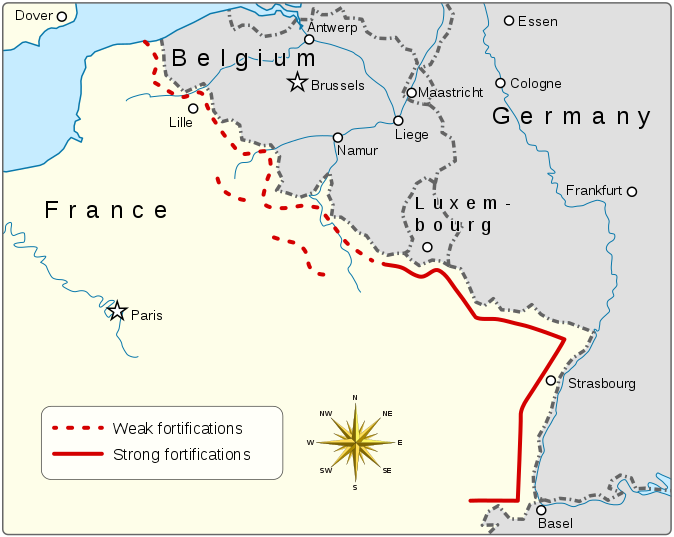

The defensive plan relied on the Maginot Line, an impressive string of fortifications along the Franco-German border. The French believed that, by holding the Germans there, they could prevent their country’s fall.

The Plan of Attack

Developed by Erich von Manstein, chief of staff for Army Group A, the German invasion plan was a bold one.

Army Group B would invade the Netherlands and from there move into central Belgium. A substantial attack in its own right, this would act as a distraction, drawing away French and British forces.

Meanwhile, Army Group A would launch a swift assault through the Ardennes forest. Allied defenses there were minimal, as they did not believe that an army could effectively advance through the forest.

By doing so, Army Group A would outflank the Maginot line, avoiding an attack on its hardened defenses, before sweeping north to reach the Channel coast and split the Allied armies. France would be left vulnerable and so have to surrender.

Breakthrough

The German plan went like clockwork.

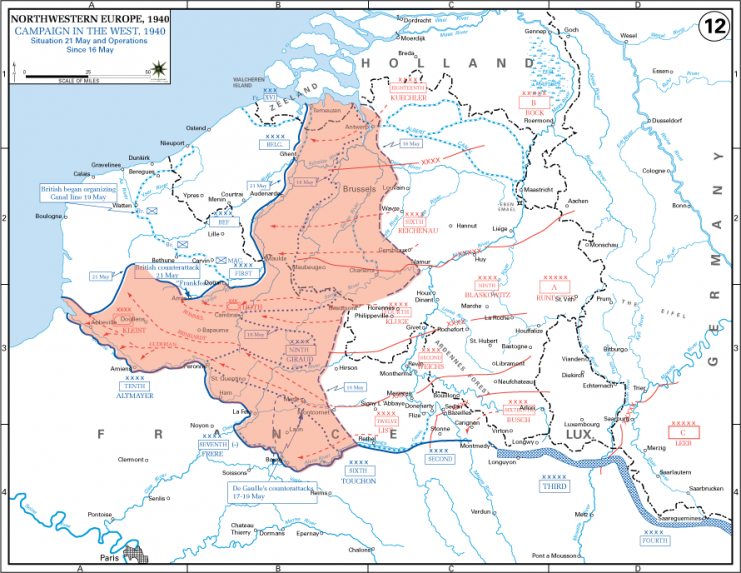

On the 10th of May, as Army Group B began its invasion of Holland, Army Group A raced through the Ardennes. They caught the Allies completely by surprise and within two days had reached the River Meuse, two days sooner than the Allies had thought possible.

Under the dynamic command of Heinz Guderian and Erwin Rommel, German divisions attacked across the Meuse on the 13th, creating a bridgehead on the far side despite stiff resistance.

Failure to Counter-Attack

If the Allies could have counter-attacked while the Germans were establishing their first bridgeheads, then they might have stopped the advance. But the Germans had deliberately hit the point where two French armies met, making it harder for the defenders to coordinate.

Rather than counter-attack, General Corap of the French Ninth Army ordered a retreat that turned into a rout, while the Second Army was driven back. British and French bombers took heavy casualties attacking bridges at Sedan without success.

The British launched one substantial counter-attack, against Rommel’s forces at Arras on the 21st. But while this caused a brief moment of hesitation, it was not enough to seriously impinge upon the advancing armies. By the 23rd, it had been swept aside.

Reaching the Sea

By the time of the attack at Arras, the Allied armies had already been split in two. Guderian, a master of armored warfare, reached the Channel coast at Abbeville on the 20th.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), remaining Belgian troops, and a portion of the French Army were cut off from the main French force, squeezed between the advancing Germans and the sea.

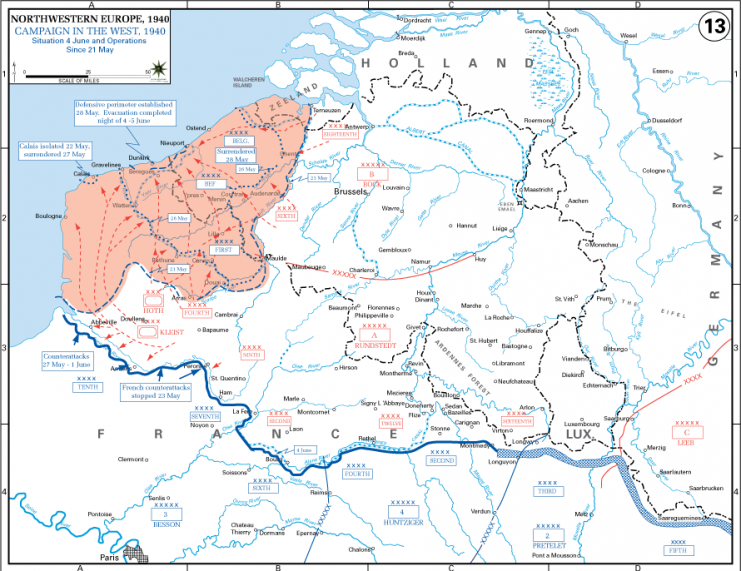

The Pause at Dunkirk

Believing that the British were now doomed, Hitler ordered a pause on the advance in that sector, which lasted from the 24th to the 27th. He had several reasons for this, including resting the armored divisions and giving the Luftwaffe a chance for glory by bombing the British into submission.

The pause proved to be a mistake. Over 300,000 British, French, and other Allied troops were evacuated from the port of Dunkirk, providing Britain with the troops it would need to continue the war.

This mistake could do nothing to save France.

Operation Fall Rot

With the British gone and the Low Countries defeated, the Germans could turn their focus towards the heart of France.

On the 5th of June, they began Operation Fall Rot (Case Red), the second stage of the invasion. German troops pushed south from the positions they held along the Somme.

The French had had time to reorganize and now better understood their opponents. For two days, they held up the German attacks. Then Rommel broke through the French lines and headed south-west, crossing the Seine on the 9th.

Other German forces broke through to the south-east and headed for the border with Switzerland, encircling French troops still on the Maginot line.

The Politics of Surrender

The army was in disarray. Refugees were streaming west. Germans were advancing on Paris.

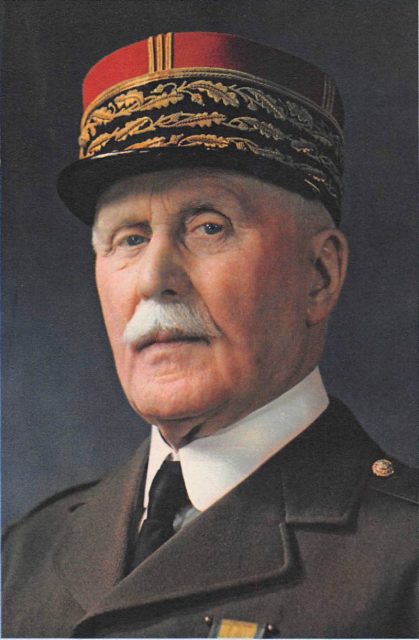

Even before the Dunkirk evacuation, some members of the French cabinet had been urging an armistice. Prime Minister Paul Reynaud found his political support falling away in favor of his deputy, Philippe Pétain, a right-winger and military veteran who urged immediate peace to save France from further losses.

On the 16th, Reynaud resigned and Pétain took over. Six days later, France surrendered. The country was divided, half occupied by the Germans, the other half a satellite state led by Pétain.

What Went Wrong?

How did things go so wrong for one of Europe’s great powers?

Low morale was a factor in French defeats. Superior German equipment played a part. Even the Allied command structure, which was complex and cumbersome, contributed to the outcome.

But the biggest problem was a flawed strategy. The Allies failed to foresee Germany ignoring the Maginot Line in favor of an attack through neutral countries. They ignored the possibility of an advance through the Ardennes.

They were outmaneuvered by an army whose commanders had more imagination and flexibility than they did.