It did not take long for other armies to adopt camouflage, and each nation did theirs differently.

The Great War changed the world forever. A modern war of unparalleled destruction, the conflict destroyed empires, crumbled regimes and redrew the map of Europe. Through the carnage, mankind created the brutality and ingenuity of modern warfare.

One innovation of the war was camouflage. In the first months of the war, garishly uniformed soldiers marched into battle to be cut down by machine guns and artillery shells. As the Entente and Central Powers dug in for a long war, armies learned the need to conceal themselves against enemy fire.

Eventually all the belligerent powers adopted camouflage, but the French were the first to institute a dedicated unit whose sole purpose was camouflaging. The word itself is of French origin, based on a verb referring to stage painters. The camouflaging men themselves during the war were called camofleurs.

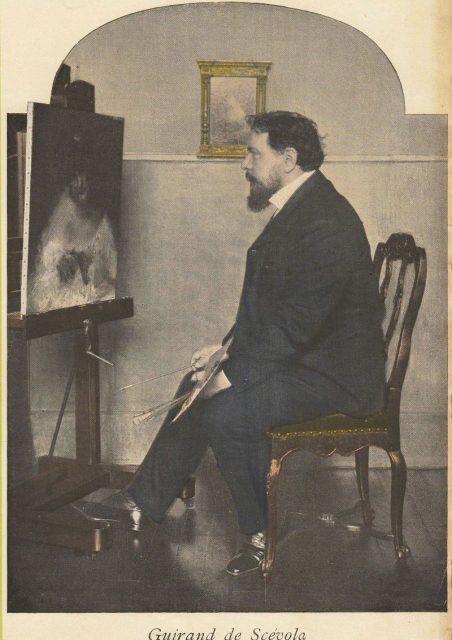

The first to come up with the idea of camouflage as we know it were two painters drafted into the 6th Artillery Regiment, Lucien Victor Guirand de Scévola and Louis Guingot. By August of 1914 the two artists used canvas cloths painted in natural colors to obscure their guns from enemy spotters.

Though wearing less conspicuous uniforms than the infantry, French artillery still wore a needlessly garish blue. The two pioneering artists also created cloaks in natural colors to make them harder to spot against the muddy backdrop of the Western Front.

These initial camouflage efforts proved so successful the Minister of War took personal interest in its use. On August 14, 1915, the French created a dedicated Camouflage Section, establishing workshops to create the concealing equipment first envisioned by the artillery artists-turned-soldiers.

Though artists of all types were recruited, those with a cubist’s eye for vision-disrupting patterns, as well as set painters and stage directors, received ample representation.

The main workshop for camofleurs in Paris trained over 200 experts in artistic concealment. Other workshops worked with specific army groups to cater to the camouflage needs in their respective combat zones. Along with the artists themselves, tradesmen such as steel workers, carpenters, and plasterers were in high demand in the shops to support the camofleurs.

Operating similarly to scouts, camofleurs first investigated a combat zone to get an idea of the terrain layout and coloration. They then produced appropriate camouflage.

https://youtu.be/MZJ4Smpn5jA

One of their more daring efforts were replica trees placed in the middle of the night. No Man’s Land left no shortage of ruined tree trunks, and the camofleurs replaced some of the destroyed trees with fake ones to serve as observation posts.

More mundane efforts included netting for artillery, and canvases and bushes for roads, train tracks, buildings, and sometimes entire villages. Camofleurs also built decoy buildings and even moved buildings to throw off enemy observation.

It did not take long for other armies to adopt camouflage, and each nation did theirs differently. The Germans used mainly browns and greens in a pattern later adopted by the United States when they entered the war. Both the Entente and Central Powers developed their own camouflage workshops and learned how to use irregular patterns and decoy buildings to disorient the enemy.

Regardless of the colors, camouflage changed warfare in a way unlike the deadly machines of the Great War. Rather than developing new ways to kill others, the French camofleurs developed ways to keep their own soldiers alive.

From garish uniforms easily spotted by the enemy to more muted uniforms and patterns, warfare was changed forever. The lessons learned in the Western and Eastern Fronts would be further adopted – or ignored – in the next war, when new, ever more creative camouflage entered the warzone.