On August 10, 1512, French and English fleets clashed off the coast of Brittany. It was a battle that destroyed the most powerful ships on both sides. Five centuries later, historians are still hunting for their remains.

The Battle of Saint-Mathieu

The War of the League of Cambrai was mostly fought in the Italian Peninsula. But when England joined the fray in April 1512, it brought the fighting to the Channel. A fleet commanded by Edward Howard transported an English army to attack France, then set to raiding along the coast and harassing enemy shipping.

France and Brittany assembled a fleet to stop Howard. The two countries had recently been united through a dynastic marriage, and this would be the first time since then that they fought together against a common foe. The last time they fought, it had been on opposing sides, so this was a powerful, symbolic moment.

The English caught their opponents assembling off the coast at Brest and attacked them. In a panic, the French and Bretons cut their mooring ropes and set sail for the shelter of the port. Their two largest ships, the Marie la Cordelière and Petite Louise, covered the retreat of the rest.

The Cordelière, under Breton captain Hervé de Portzmoguer, sailed straight towards the largest English ship, the Regent. The surrounding English ships damaged the Petite Louise, forcing her to retreat. The Cordelière was left alone.

The crew of the Cordelière caught the Regent with grappling lines and began boarding. Fierce fighting raged, with other English ships sending their crews to the Regent as reinforcements. The decks were soon painted red with blood.

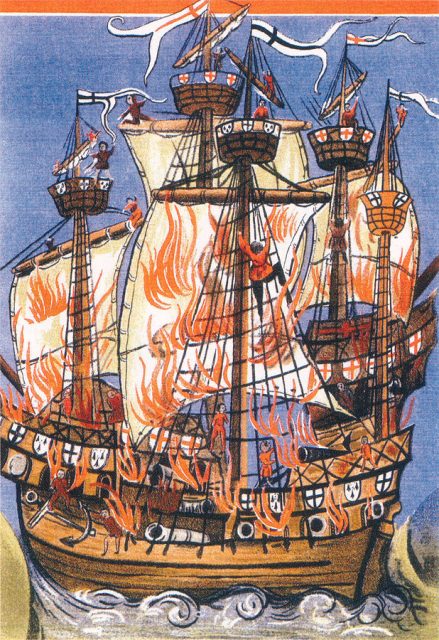

Suddenly, there was a roar and a burst of flames. The powder magazine of the Cordelière had caught fire and exploded. Flames engulfed both ships, killing many of the furiously battling sailors. Still bound together, the two ships sank beneath the waves, taking their crews with them. Of the 1,710 crew across the two ships, only 80 survived.

The Battle of Saint-Mathieu became an iconic moment for the people of Brittany. Poems were written about it, depicting Hervé de Portzmoguer’s death as a heroic act of sacrifice and the battle as a moment of unity between Brittany and France.

The remains of the ships were lost to the deep.

Re-examining the Evidence

Five centuries later, French scientists and explorers are searching for the remains of the lost warships. A team led by Michel L’Hour are using the André Malraux, a surveillance ship from the French culture ministry, on a mission to find and retrieve what was lost on that tumultuous day.

L’Hour is a grey-bearded marine archaeologist with decades of experience unearthing France’s past. He has long been fascinated by the ships lost at Saint Mathieu. Now, he has gathered a team of specialists from different disciplines to join him on his quest.

It’s a fascinating challenge they face. As with many battles of that era, there are few accounts and a shortage of details about what happened. This makes it challenging to find the spot where the ships went down in flames.

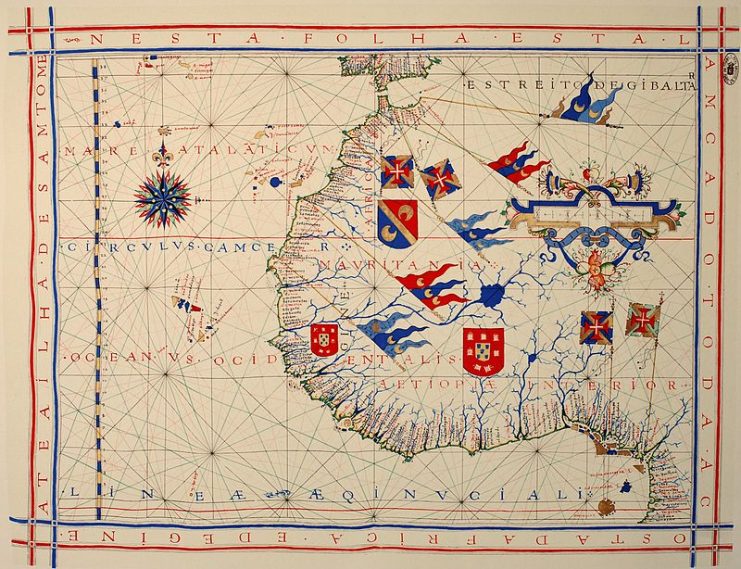

Tides and currents from that year have been calculated and compared with reports of the action. During previous attempts to find the site, archaeologists failed to factor in a calendar change from 1582, which threw out their calculations. L’Hour’s team hope that, having taken this change into account, they can more accurately represent the flow of the sea that August.

Such data is being combined with naval charts of the sea floor as well as a surprising source: diplomatic correspondence. In the aftermath of the battle, the bodies of Englishmen lost on the Regent were washed up along the Breton coast. These included many noblemen whose families sought to have the bodies repatriated.

As a result, there are records of where some of these bodies washed up. By following the currents back from these locations, the archaeologists can build a better picture of where the battle was fought.

Into the Depths

Using the accumulated evidence, L’Hour has narrowed his search down to a section of sea north of the village of Camaret-sur-Mer. Having relied on ancient documents to reach this point, he is now using the latest technology to complete the mission.

Criss-crossing the waters of the bay, the André Malraux drags an array of detection equipment behind it, including magnetic sensors and radar. A remotely controlled robot is used to examine what the sensors find, sending back video footage for the team to examine aboard the boat. If they find something with potential, then divers can be sent down to take a closer look.

So far, they’ve had one very promising find. Early in the survey, they discovered the wreck of a ship whose overlapping planks, known as a clinker build, showed that it was made in the 15th or 16th century – exactly the right time for the Battle of Saint Mathieu. Hopes rose that their research had already paid off.

Sadly, the wreck was missing one vital feature: cannons, which were definitely carried by the two lost ships. The battle may even have been the first in which both sides had cannons firing through purpose-made ports in their hulls. Without such weapons, it became clear that this was neither the Regent nor the Marie la Cordelière.

Read another story from us: The Battle of Hastings: The Last Successful Invasion of England

The search continues. With the backing of the French government and local Breton authorities, L’Hour still hopes to retrieve the Cordelière from the depths, to be preserved and displayed in the region where it was so celebrated. Like its sister ship, the Mary Rose, the Regent too may one day return to the light.

Until then, the explorers continue. With ancient documents and modern technology, they seek out a site of local legend.

Someday soon, the sea may give up its dead.