For many years after World War II, the French government and many historians, reeling from the experience of war and occupation, put forward a narrative of what had occurred in France during WWII.

The narrative ran along these lines: Though there were some who joined the Nazis and supported the collaborationist Vichy government of Marshal Petain, most of France’s citizens were loyal to the “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity!” ideals of the French Revolution.

They fought as best they could against the occupiers and their traitorous henchmen, whether that meant actually fighting in the Resistance, or acting against the occupation in other ways.

The truth, as many people knew, was far different. This view did not get much attention until Marcel Ophul’s classic documentary The Sorrow and the Pity (1969) examined the war years in the area around the central French city of Clermont-Ferrand. It became clear to all who watched that film that the war years in France were not so clear-cut.

A sizable minority joined the Resistance and fought the Nazis and their collaborationist partners. However, another large minority were collaborators, which the governments of post-war France wanted downplayed to the utmost.

Most French people tried to get along the best they could under very trying circumstances. Some even worked both sides, such as Francois Mitterrand, who dominated French politics in the 1980’s.

Life under Nazi occupation was examined again in the 1980’s because it came out that the Mitterrand had in fact worked for Vichy in the early years of the occupation and then joined the Resistance in 1943 – when perhaps the tide was turning. The Mitterrand story caused a great deal of self-examination in France.

Now, in 2018, comes a new book and companion film by historian Laurent Joly and film-maker David Korn Brzoza, which shine a light on the extent of French police involvement in the deportation of French Jews to the Nazi death camps.

The book, entitled L’Etat contre les Juifs (The State against the Jews), and film The Vichy Police show the extent of police involvement which ran deep.

Even before the war, the French police, particularly those in Paris, kept an amazingly detailed catalog of the refugees coming into the country from Germany, Austria and other areas falling under Nazi control. Like most police forces in the world, the French police was a conservative branch of government.

In the world of French politics in the inter-war years, this meant that there was significant anti-Semitic sentiment. Not only did the French police have dossiers on many of the refugees coming into France, but already, many French police departments also had files on France’s Jews, whom they considered to be a leftist and foreign influence.

Therefore, when the Nazis marched in, they had very little work to do in finding and classifying France’s aliens and Jews. The most notorious round-up of Jews in France took place on July 16-17, 1942.

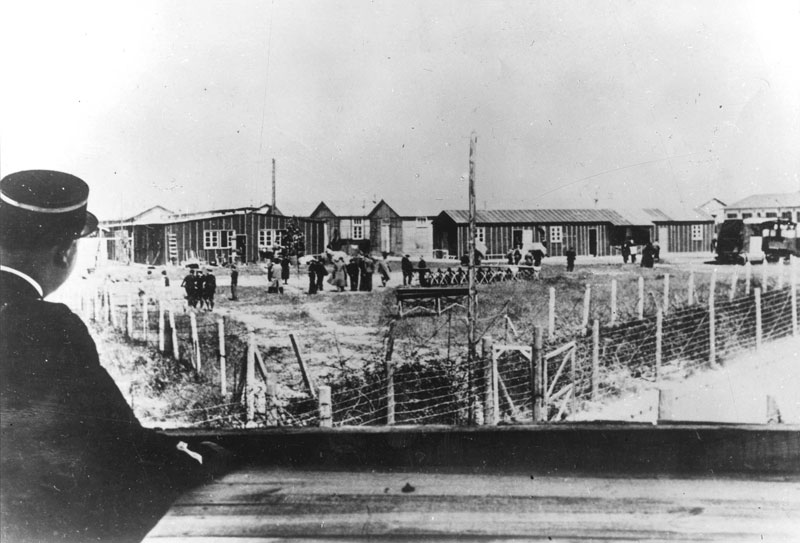

In what is known as the “Vel’ d’Hiv” round-up (for “Velodrome d’Hiver”, an indoor bicycle racing venue), the Nazis herded 13,000 foreign-born Jews into the small stadium prior to deportation to the death camps. The conditions at the velodrome were abysmal, and the French police saw it with their own eyes. Nothing good was in store for these people.

To do all this, the Nazis needed the help of the French police. Many of these men told themselves that the foreign Jews “weren’t French” so they were really doing France a favor by removing a potentially dangerous population.

Obviously, the infants, children and elderly that were rounded up were not dangerous, but when people do something against their better nature, they need justification.

In their research, Joly and Brzoza found previously overlooked and unknown documents in the archives, along with the only known extant picture of the Vel d’Hiver roundup, which shows police vans and officers standing around outside the stadium on the day of the deportations.

On November 10, 1942, the Germans marched into previously unoccupied Vichy France, but even before that, Joly and Brzoza show, the Vichy police were already supplying the Nazis with information on Jews in the territory.

When the Germans moved in, the French collaborators moved against the Jews. They sometimes did this without prodding from the Germans, actually taking the Germans by surprise.

The author and film-maker state that “Vichy was always trying to demonstrate its goodwill towards the Germans…. There were ways in which they could have resisted their pressure. But the policy of collaboration was a deliberate choice.”

Sometimes that choice was made due to anti-Semitic feeling. Sometimes it was to show the Germans that the authorities were going to “toe the line” and hopefully get the Germans to allow the French the semi-independence they had enjoyed until then.

Throughout the book and the film, Vichy officials are shown to have acted prior to being given any instructions by the Germans. They even went so far as to give a Gestapo official an office in French government buildings, even though that was not part of the armistice, nor was it requested by the Germans.

Joly and Brzoza also elaborate on various different cases which show the depth of French police collaboration, from handing over to the Nazis two German refugees who had Vichy passes to leave for the United States, to rounding up 40,000 Jews in 1942 alone, mostly by the French.

Read another story from us: After Dunkirk – The French Fallout

After the war, many Vichy officials used one or both of two excuses for what they did. Either they saved as many Jews as they could given the extreme circumstances, or that they were police, and the job of the police is to “follow and uphold the law – not write it.”

They should have been exposed to the saying of the American journalist and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who said about slavery “That which is not just is not law.”