The slums of New York City were notorious in their time for producing some of the most desperate, bloodthirsty, and depraved gangs and gangsters in American history.

Before organized crime took root in the Republic, the gangs of New York carved out their fiefdoms in blood and liquor. Backed by political machines desperate for votes and with the police paid off or hampered by their bosses, the gangs, especially those of the infamous Five Points, became legends unto themselves.

Even into the twentieth century, the gangs made their presence known. Their leaders entered the lexicon of the great gangsters of the world.

Some managed to make names beyond their fiefdoms, others grew to national prominence, and some managed to redeem themselves. Such was the case of one early nineteenth-century gangster known by the name of Monk Eastman.

Born Edward Osterman, Monk Eastman led the appropriately named Eastman Gang. In an era of colorful gangs and gang leaders, Eastman stood out thanks to his leadership skills and appearance during the end of the gang era as the nineteenth century understood it.

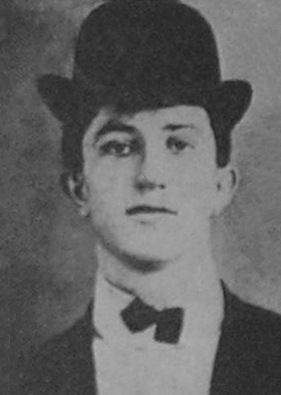

Eastman’s appearance epitomized the stereotypical gangster. Early underworld historian Herbert Asbury described him as having “a bullet-shaped head, and during his turbulent career acquired a broken nose and a pair of cauliflower ears…” He also had striking veins, saggy jowls, a short, thick neck, and messy hair — all topped off by a bowler hat several sizes too small.

The man looked so much like a gangster he could have filled in for a Dick Tracy or Bugs Bunny villain.

Despite (or perhaps partly because of) his appearance, Eastman rose through the common thugs of the East Side to command a force all of his own. At one point, as many as 1,200 thugs looked to Eastman for leadership.

He and his men controlled the area near the Bowery and 14th Street, constantly fighting with other notorious gangs such as the Five Pointers.

Extremely fond of birds and cats, the gangster was also fond of black-jack, clubs, and brass knuckles. With these and his army of thugs, Eastman carved out a domain in New York. His gang used ruthlessness to make a brutal, dishonest living however they could.

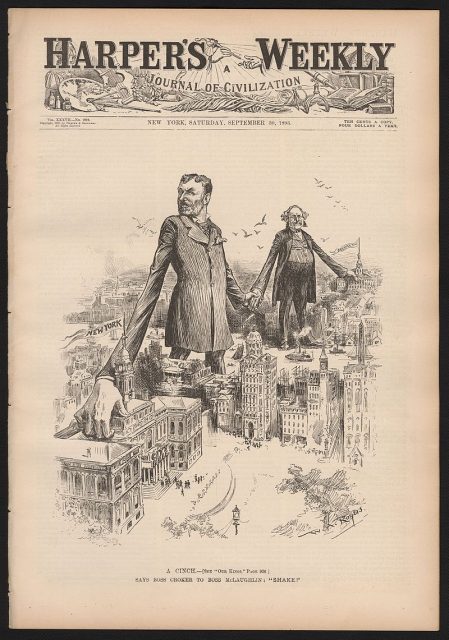

Such effective brutality gained the attention of Tammany Hall, the notorious Democratic Party machine in New York. With their patronage, the Eastman Gang went to work helping to rig elections.

Tammany’s protection made it almost impossible to arrest Eastman. Whenever one of the honest policemen collared him, the politicians saw to his release. Even Tammany, though, had its limits. That limit was reached in 1903 when the Eastman gang got into a fight with their old rivals the Five Pointers.

Taking place under a bridge, the Battle of Rivington Street saw widespread use of firearms. Rather than beat each other with clubs and bricks, the thugs took potshots at each other from behind bridge pillars. For several hours, a hundred gangsters filled the area with flying bullets.

Though few died, the sheer terror of such massive gun violence in the city frightened the populace and roused the politicians to action. When Eastman was arrested the next year in 1904, Tammany failed to provide support. Eastman spent ten years in Sing Sing.

When Eastman finished his time, the gang was gone, splintered by his lieutenants and weakened by gang fighting and reformers. Still looking for a fight, in 1917 Eastman signed on with the National Guard.

Covered in scars together with a broken nose and what remained of his ears, the examination doctors couldn’t help but wonder aloud what the last war was in which Eastman participated.

The former gang leader, now known as William Delaney, merely replied, “Oh, just a lot of little private wars around New York.” The doctors, not one to turn down a man who knew how to hold his own, let him pass.

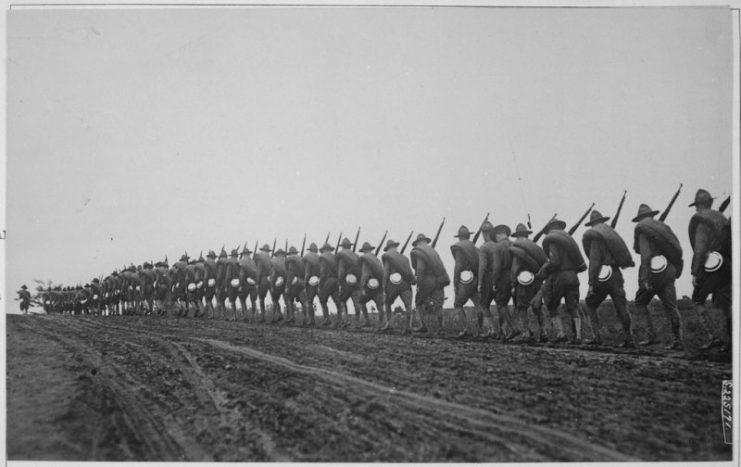

When the United States entered the Great War, the New York National Guard went to Europe as the 106th Infantry, 27th Division. They were known as O’Ryan’s Roughnecks. With them, the 44-year-old gangster found himself transformed from convicted felon into war hero.

Monk served with distinction throughout his tour. Heedless of danger, fatigue, or his old wounds, Monk routinely recovered wounded soldiers from No Man’s Land, even rescuing his wounded sergeant on one occasion.

He had no qualms about ducking from shell crater to crater to take out machine gun nests. When he was wounded or his unit sent to the rear to rest, he routinely insisted on staying at the front.

After surviving a gas attack, he snuck away from the hospital, filched a uniform, and went back to the war.

When he was later asked what he thought of the war, he would shrug and say, “There were lots of dance halls in the Bowery tougher than that so-called ‘Great War’ of theirs.”

Though Monk earned no medals for his valor, he obtained something just as valuable. Having returned to New York and been lauded for his deeds, Eastman received back his citizenship.

Unfortunately, Monk still had enemies in the streets. Near the end of December 1920, Monk was shot dead. He received a full military funeral followed by thousands of mourners.

Though some whispered that, near the end, he had gone back to his old ways, to his buddies from the trenches he was not the ruthless gangster Monk Eastman but the hero William Delaney.