More than forty years have passed since the end of the Vietnam War, easily the most controversial war the United States was ever involved in. Even after all of this time, the debates around US involvement in the war are still heated. Opinions vary about why the US got involved, whether successive administrations knew the war could not be won, whether the armed forces of the US could have won the war if “Only the politicians had let us,” and so on.

All things being equal, if you were a visitor from another planet who was familiar with Earth’s history up until 1969-72, and were presented with an in-depth military report on the hard facts, figures, and data surrounding the US involvement in Vietnam, and were then presented with the question “Which side do you think won the war?,” it would be easy to understand why you might pick the American side.

Far more casualties were inflicted by the Americans on the Vietnamese than vice-versa. The United States had command of the air, the sea, and–where it chose to–the ground. Its troops were better equipped and better armed.

Not a single hostile Vietnamese ever invaded the United States, nor can one be proved to have caused an American casualty outside the Southeast Asian theater of war. Based only on those few facts, any person (or alien) in their right mind would assume that the United States easily won the Vietnam War.

What are the reasons that the US lost the war?

The first two reasons are the converse of each other: the Vietnamese, in this case meaning the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), were highly motivated to win the war. The Americans were not nearly motivated enough.

By the latter half of the 20th century, many in the West were exhausted by wars. In contrast, the Vietnamese were fighting a perceived foreign invader – the latest in a long line of them. With the uniting ideologies of communism and nationalism, the Vietnamese felt they were on the brink of having a unified nation for the first time since before the arrival of the French in the 1800’s.

American involvement peaked in 1968 when over half a million US troops were “in-country,” but most of those troops were draftees, sent for one year to “do their bit.” Their main goal was to get out of Vietnam alive, which leads us to the next problem American forces experienced.

No one ever effectively articulated to the American public or military the reasons for US involvement in Vietnam. Firstly, when the US became more heavily involved in 1965, most Americans couldn’t find Vietnam on a map. When told that Vietnam, a relatively, small, poor and backward nation thousands of miles away posed an existential threat to the US as part of a chain of domino nations that would each fall in turn to Communism, most Americans couldn’t see it, including their troops.

American forces were hampered by rules of engagement. Of that there is no doubt. There were to be no American troops north of the DMZ (“de-militarized zone”) of the 17th Parallel that separated South from North Vietnam. Violating that “rule” ran the risk of bringing Communist China into the war, as had happened in Korea. To heighten that threat, by 1965 China was armed with nuclear weapons and was led by the increasingly erratic Mao Zedong.

Vietnamese troops used supply routes in Laos and Cambodia to funnel the necessities of war to South Vietnam. While American special forces teams operated in Laos in the early-mid 1960’s, by the late 1960’s that was a lost cause, despite an additional massive bombing campaign.

Another roadblock in the rules of engagement occurred when US troops were exposed as having operated in Cambodia contrary to what the Nixon Administration promised. After Congress, which was already concerned with the length of the war, dissent in the US, costs, etc., found out about the incursion, it threatened to stop much of the military funding for the war. The only thing the US military could do after that was bomb the so-called “Ho Chi Minh Trail,” the supply route leading from North Vietnam into the South, on its western borders.

Within South Vietnam itself, America was faced with an ineffective and corrupt allied government that was hated by its people. Many South Vietnamese felt the US propped up people worse than the Viet Cong. Despite the cruelty often showed by the Viet Cong, when push came to shove many South Vietnamese chose, however reluctantly, the side that was perceived as not corrupt and not working alongside “Western colonialists.”

Within the United States itself, the war engendered increasing opposition in the United States. The reasons above, plus the lies of successive administrations dating back to the JFK era about the war, were too much for many people. By 1973, when the US pulled almost all of its ground troops out of Vietnam, it was not just “the hippies” that wanted American involvement to end. Increasingly, the taxpaying middle classes were against the war too – and Nixon knew if he had lost them, the war was over.

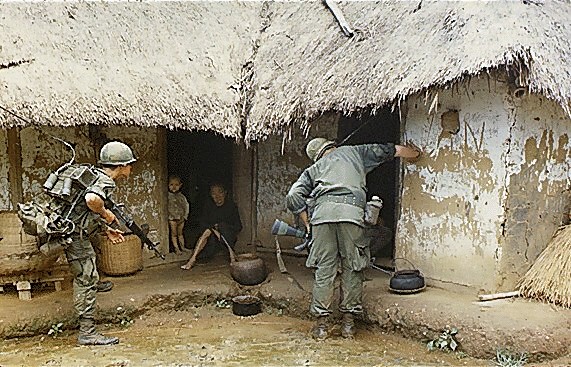

According to Gallup, in 1965 most Americans supported the war. Gallup took the same poll in 1968 – most Americans were against it. This was due to a number of factors, not least of which were images of dead and wounded Americans, civilians, and war crimes committed by US troops.

Read another story from us: How Vietnam Changed U.S. Perceptions of War at Home

Most people knew that the VC and NVA committed atrocities, but until the Vietnam War, Americans were imagined as being above that. The reality of those images was shocking at the time.

Vietnam defied almost everything America knew about war – or perhaps, the conflict showed Americans how much they had forgotten, since just under two hundred years before, a smaller guerrilla force in the Colonies had defeated the world’s largest power.