Genghis Khan also encouraged philosophers, mathematicians, scientists and artists from all over the empire to meet and work together.

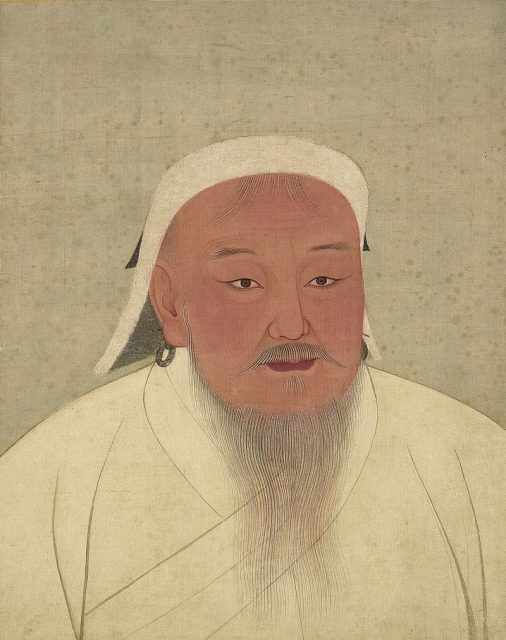

Genghis Khan is one of the most recognized figures in history, and is either portrayed as a bloodthirsty, all-conquering tyrant, or a visionary leader whose progressive ideas were far ahead of their time.

Opinions on Genghis Khan (birth name Temujin) can obviously be quite polarized, but the truth of the matter is that, like most people, he was a complex individual with both flaws and strengths. What cannot be denied about him is the sheer scale of what he achieved, which is virtually unequaled in human history: the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever seen.

Genghis Khan was born around 1162, and was the second son of the Kiyad chief (the Kiyads were one of the tribes of the Mongol confederation). He endured a difficult childhood, in which his father was killed by the rival Tatar clan and his family was expelled by his clan. He, his mother and his siblings were forced to survive in the wild by scavenging and hunting.

He was captured by the Tayichi’ud tribe and made a slave for a time, and his wife Börte – he got married in his late teens – was kidnapped for a time by the Merkit tribe. He got her back, though, and began to establish himself as a formidable warrior and shrewd leader by his early twenties.

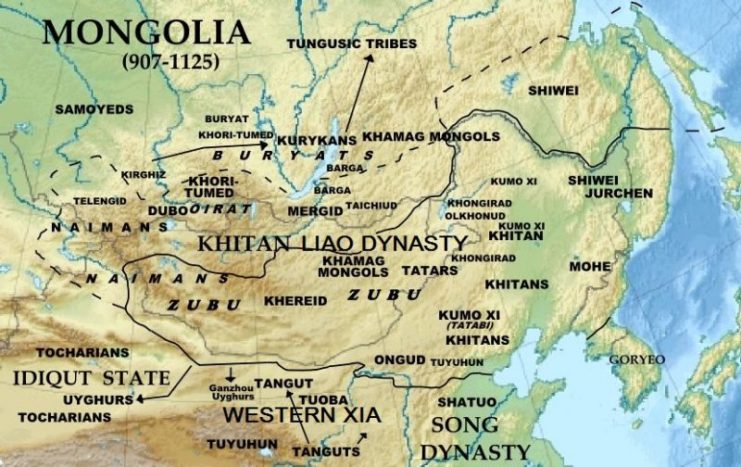

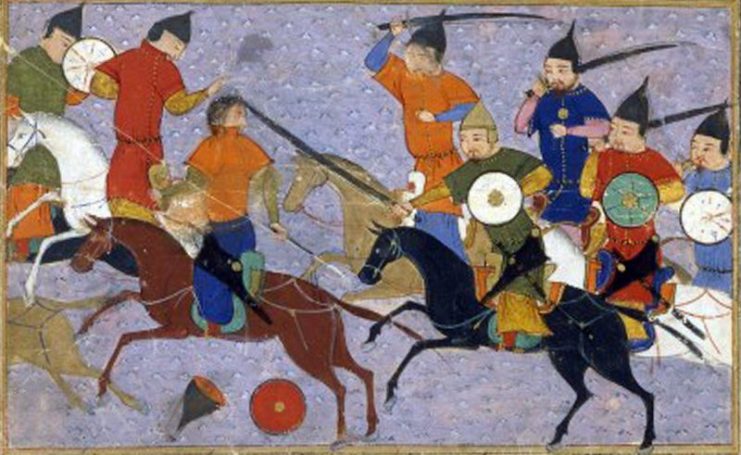

Through both conquests and the forging of strategic alliances, he had united the tribes under the Mongol banner by 1206, and after this began to expand his sphere of influence outward. What had been a confederation soon became an empire, and continued to spread outward in all directions for many decades, both up to and well after Genghis Khan’s death in 1227.

While there is no getting around the fact that this empire was forged by violent conquest, and the fact that tens of millions of people would ultimately end up dead as a result of the Mongol conquests over the course of the 13th century, Genghis Khan did do some good during the establishment and expansion of his empire, and many of his ideas were undoubtedly progressive for the medieval era.

Firstly, in terms of good, Genghis Khan allowed freedom of religion throughout his empire. Unlike most empire-forgers before him (and many after him), he was not fanatically devoted to any one religion.

While he followed Tengrism, an old religion native to Central Asia that was characterized by shamanism, animism and belief in the spirits of nature, he allowed complete freedom of religion for all citizens of his empire.

He consulted Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Taoist and other missionaries and religious leaders, expressing an interest in the philosophies of their various faiths, particularly in his older years.

He also established what we would now call an international courier or postal service, which he named the Yam. Under the Yam system, a great number of post houses were established across the length and breadth of the empire, at which a rider could change his tired mount for a fresh one.

In this way messages and goods could cover distances of up to two hundred miles in a single day. This also proved extremely useful for gathering intelligence and planning military campaigns.

Genghis Khan’s empire also created a period of stability and safety that had not existed before. Travelers from Europe were free to take their caravans across central Asia as far as China via the Silk Road, and vice versa, creating a period of economic prosperity and forging links of international trade.

This not only fostered economic prosperity, but it also developed many trades, crafts, and arts by diversifying markets and exposing various craftsmen, artisans, and artists across the empire, from Europe to China, to styles, materials, and methods they would not otherwise have seen.

Genghis Khan also encouraged philosophers, mathematicians, scientists and artists from all over the empire to meet and work together. The academies and institutes of art, philosophy, and science that formed throughout the thirteenth century enriched the cultural and intellectual landscape of his successors’ khanates.

Genghis Khan was also a proponent of another very progressive idea for the time: that of meritocracy. Almost every other minor and major regional power at the time passed on titles and power via hereditary means. They did everything they could to ensure that “high-born” men inherited power, land, titles, and leadership roles, and that “low-born” commoners could never hope to attain such things.

Photo by Classical Numismatic Group CC BY SA 2.5

Genghis Khan, however, took the opposite approach, one that was quite revolutionary for its time. Anyone who proved his worth by virtue of his talent, bravery, military skills, and loyalty could rise to the very upper echelons of leadership, regardless of his birth and background.

This even extended to former enemies. Genghis Khan preferred to offer conquered soldiers the chance to join his army and fight for him, with the promise of rewards for loyalty, rather than simply imprisoning, enslaving or executing them, as was common practice for the time.

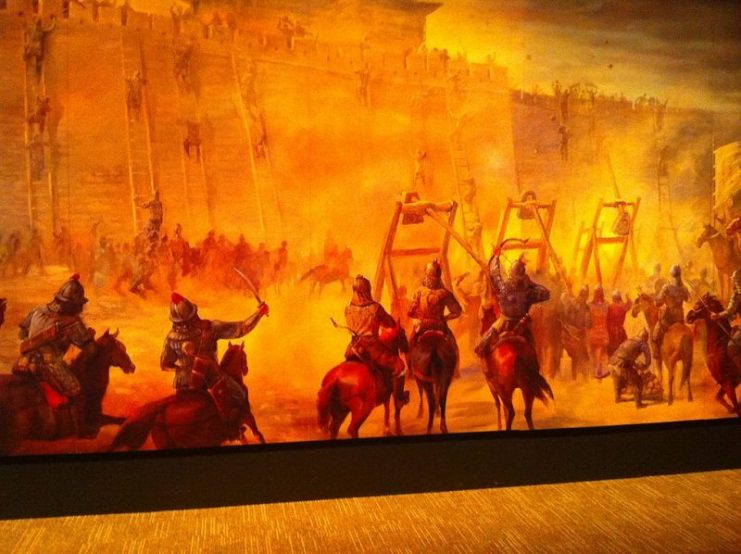

Also, Genghis Khan usually offered those he was intent on conquering the chance to submit peacefully, generally without any majorly negative consequences, before attacking them. If they agreed to submit, their cities and towns would be spared and nobody would be harmed – but if they refused this offer he would crush them without mercy.

Despite all these good things he may have done, and regardless of the widespread peace and international trade routes that were established due to the expansion of the Mongol empire, there is still no getting around the fact that Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes were incredibly violent and brutal.

The final tally of human deaths as a result of the Mongol conquests is estimated at around forty to one hundred million – which was close to eleven percent of the entire world population at the time. Entire towns and cities were razed to the ground, and every living thing in them put to the sword.

Read another story from us: The Stirrup: Genghis Khan’s Deadliest Weapon

Overall, while it is easy to remember Genghis Khan only as a bloodthirsty warlord and brutal conqueror, it is also necessary to remember that he did not only kill, sack, loot and plunder – he managed, during his extraordinary rise to power and his reign, to do some rather good things too.