The Third Reich, a nation built on drugs. This title reaches all the way up to the upper echelons of the Nazi hierarchy.

We all know that the Reichsmarschall and the head of the Luftwaffe, Herman Goering, was addicted to morphine. But what about the Führer himself?

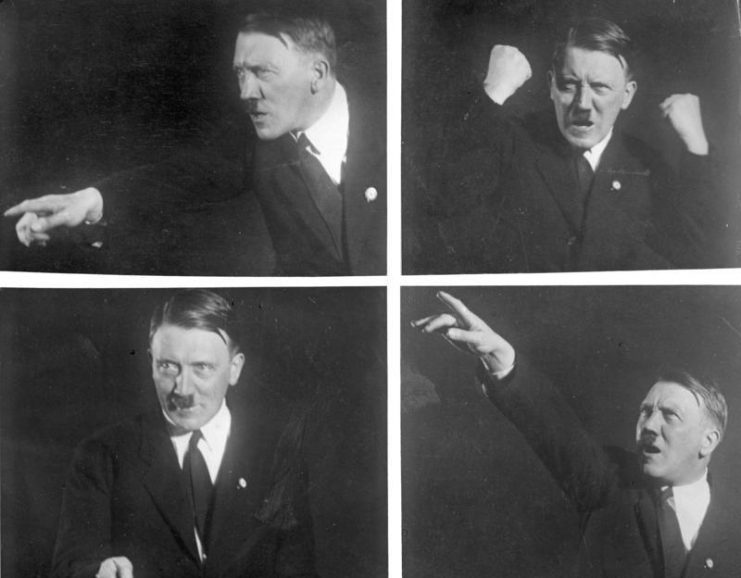

If historical sources are anything to go by, Adolf Hitler consumed large quantities of a special drug that kept him going despite fatigue.

No wonder the man could shout for hours on end. And, as always, the self-acclaimed munificent Führer shared his wisdom and bounty. What was good for Hitler was good for his troops. As a result, he invaded most of Europe with an army of junkies.

This drug abuse reached all the way down to the simple soldier of the Wehrmacht.

In retrospect, it makes sense. Have you ever asked yourself how the Germans were able to achieve quasi-superhuman feats during the invasions of France and Poland in 1939 and 1940 respectively?

It was not thanks to fitness and training alone. Not even cocaine or morphine, which were readily available in Nazi Germany at the time, were the culprits. In any event, the aforementioned drugs were considered “Jewish” by the regime.

So an alternative was needed, something suitable for the so-called superior Aryan race.

The Nazi chemist Fritz Hauschild had the solution

Hauschild developed something that was closely related to the body’s adrenaline. Furthermore, it was soon discovered that the new miracle medication worked well against asthma, promoted endurance and concentration, and enhanced a person’s mood.

The German pharmaceutical company producing the stuff was open to all kinds of pick-me-ups. They did not even shy away from products like chocolates mixed with the solution. After all, millions of German housewives also needed something to keep them going.

It did not take long for the military doctors to become aware of this alleged wonder-remedy, because fatigue was one of the most significant military medical problems.

The preparation was tested on students who could solve tasks after two days and one night without sleep. The drug proved itself to be a winner. Widespread use in the army would soon follow.

It’s a fact that the results were spectacular. The soldiers of the Wehrmacht were able to march for days without sleeping, trumping the Polish, the French, and the British Expeditionary Force on all fronts.

It answers the question of how millions of German soldiers mastered the physical strain, how they managed to march over tens of kilometers per day, and how they could defy heat, cold, and the everyday violence that would knock any ordinary man senseless.

The answer lies in one word: Pervitin. This purported wonder-drug had many names in the Third Reich: Hiter’s Speed, Stuka-Pills, Goering-Pills, or Panzerschokolade (Tank-Chocolate).

It’s the same synthetic drug that is also known today by the more colloquial names of “Crystal Meth” or “Ice.” Nazi pharmaceutical factories produced the stuff on an industrial scale.

Pervitin, manufactured in the Temmler plants, was significantly purer than anything some drugs circulating today. Nazi methamphetamines came in the purest form.

The uppermost stratum of the Wehrmacht considered the drug a miracle weapon

For example, Walther von Brauchitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the Wehrmacht and one of the four highest-ranking commanders in the Third Reich, stated: “The experience of the Polish campaign has shown that in certain situations military success is decisively influenced by overcoming the fatigue of a heavily challenged force.”

At the same time, it was abundantly clear to Walther von Brauchitisch, who personally leaned toward the usual more common intoxicants such as wine and cognac, that Pervitin consumption had consequences.

“Overcoming sleep is more important in special situations than any consideration for the soldier’s health. Especially if sleep endangers military success, the security of the troops or the transportation thereof.”

The general was right to a certain extent because soldiers who were injured or killed by enemy fire as a result of fatigue certainly suffered more than if had they consumed Pertvitin.

However, even if Pertvitin had other side effects compared to modern day crystal-meth, the substance was just as addictive. This was demonstrated during the mass deployment of units for over several weeks during the Western campaign in 1940.

Temmler Werke produced 35 million Pertvitin tablets as an initial supply for the Western Army in preparation for the attack on France. In mathematical terms, that resulted in an average of 10 pills per man based on a total invasion force of 3.35 million troops.

In reality, however, the soldiers of the combat units, and especially of the storm units, received considerably more, since the supply units were not equipped with the drug.

Furthermore, Pervitin was still widely available in Germany at this time. The drug came in various forms: low-dosage contained in liqueurs and “housewife chocolate” or as tablets, which were only obtainable in pharmacies.

The “medication” had become so widespread that soldiers, who had come to know the benefits of Pervitin during the Polish campaign, often asked their relatives at home to send them parcels containing the stuff.

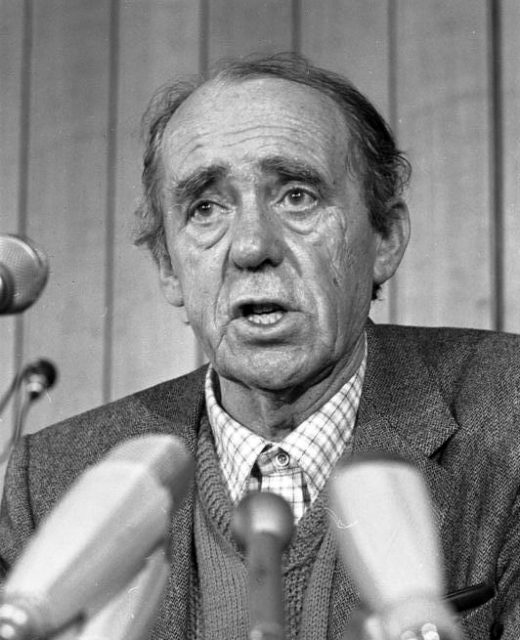

The best-known addict was probably Heinrich Böll, a young Wehrmacht soldier stationed in Poland. Several times in his letters from 1939/40, he petitioned his family with the following words: “If at all possible, please send me some more Pervitin” or “Perhaps you could get me some more Pervitin so that I can have a backup supply?”

On occasion, he even sounded like he was begging: “It’s tough out here, and I hope you’ll understand if I’m only able to write you once every two to four days soon. Today I’m writing [to] you mainly to ask for some Pervitin.”

But even before the beginning of the campaigns against Scandinavia, as well as France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, the leadership of the Third Reich knew about the dangers of the drug.

Ironically, Leonardo Conti, the Reichsärzteführer or Head Doctor of the Reich, stated in a lecture on March 19, 1940: “Whoever wants to eliminate fatigue with Pervitin can be certain that the eventual collapse in performance must one day come.”

He added, “The medication can be used against fatigue for high-performance pilots, flying for two hours or more. However, it should not be used to counter any state of fatigue, which in reality can only be compensated by sleep. This must be clear to us as doctors without further ado.”

Ultimately, Conti prevailed, and Pervitin was placed under a prescription requirement.

But there was also a countermovement. For example, at the end of 1940, a practicing neurologist recommended the prescription of the drug for a variety of indications, including psychophysical states of exhaustion of all kinds, depression, both acute and chronic migraine attacks, as well as the consequences of narcotic withdrawal therapy, anxiety neurosis, and sea and mountain sickness.

With such a broad spectrum, most Pervitin addicts would have easily found a doctor who would prescribe the drug.

For this reason, Conti commissioned a counter study in which he correctly pointed out the highly addictive potential of the drug. As of 1941, Pervitin was classified as a part of the Opium Law, so it could henceforth only be prescribed if there was a significant reason.

In spite of this, many Wehrmacht and Waffen SS units continued to fight high, as the tablets were distributed right before an offensive.

This was the case before the Battle of Kharkov in early 1943. Pervitin was also distributed in the last large-scale attack of the Luftwaffe on January 1, 1945, against air bases belonging to the Western Allies.

As the Second World War came to an end, the “Hitlerjugend,” charged with stopping the advance of the Soviet army as part of the “Volkssturm,” were given pills in addition to a bazooka. Presumably, it was Pervitin.

The fortunate few who swallowed the drug too early managed to sleep through the attack and did not die. In any case, these children, using their simple weapons, had no chance of survival against the Soviet T-34 tanks.

After the war, many addicted former Wehrmacht soldiers continued to obtain methamphetamines on the black market. Even students, who needed a quick pick-me-up to aid in their studies, resorted to the stuff.

Read another story from us: Wars in Which Drugs Fuelled the Fighting

“It will soon be back in pharmacies and socially fully accepted,” was the slogan after the war.

After the construction of the Wall, Temmler Werke in East and West Germany supplied both the German armies with methamphetamines. The German Bundeswehr continued issuing the drug well into the early 1970s.