On the far bank were two lines of French defenses featuring trenches, barbed wire, concrete pillboxes, anti-tank guns, and machine-guns.

The fall of France was one of the most important campaigns of the Second World War. The total victory the Germans achieved was made possible by two advances – one through the low countries, the other a dramatic breakthrough around Sedan.

Through the Ardennes

The German invasion began on the 10th of May 1940. Preceded by bombardments from artillery and aircraft, German armies poured across their western borders. Rather than face the French in their concrete defenses of the Maginot Line, the advancing armies went through Holland and Belgium.

Army Group A provided the southern advance. They traveled through the Ardennes forest, which the Allies wrongly considered impassable to armored formations. A quick trip through the southern tip of Belgium brought them into France facing a weakly defended part of the line.

The Germans had several big advantages in this sector. First, surprise. Second, air superiority, including the presence of the famous Stuka dive bombers. Third, superior armored formations under the leadership of two great generals – Guderian and Rommel.

Both were men who led from the front. Guderian almost landed amid the French in his reconnaissance plane, while Rommel waded waist deep into the River Meuse to work alongside his men.

Sedan

By the evening of the 12th of May, the Germans had swept through troops the French had expected to hold them for over a week.

Guderian and his forces reached the town of Sedan, where the Germans had famously crushed the French 70 years before. Fearing another such disaster, the French retreated across the River Meuse, blowing the bridges and leaving the town in German hands.

At first glance, the next step seemed intimidating. The Meuse was 60 yards (55 meters) wide and apparently unfordable. On the far bank were two lines of French defenses featuring trenches, barbed wire, concrete pillboxes, anti-tank guns, and machine-guns.

But as sharp-eyed Germans realized, those defenses were incomplete, and the two lines were too close together to be useful against modern German tactics. An assault across the river was intimidating but far from impossible.

Crossing the Meuse

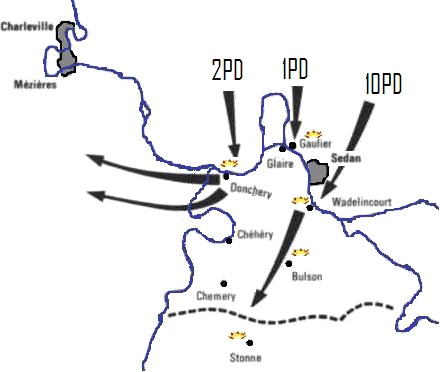

On the morning of the 13th, German armored formations poured out of the Ardennes around Sedan. The French artillery opened fire, but the crews were mostly reservists and they were short of ammunition, so the barrage was ineffective against the staggering German armor.

Late in the morning, the Luftwaffe arrived in force. While fighters fended off French aircraft, Stukas pounded the French defenses. The bombing wasn’t very accurate, but it caused terror among the amateur French soldiers, who went to ground rather than stand at their guns.

At four in the afternoon, the crossing began. Riflemen, infantry, and motorcyclists made the crossing, with Guderian in one of the leading assault boats. German artillery had taken out many of the concrete emplacements and fear of Stukas made the French far less effective.

Though some shells fell upon the troops crossing the Meuse, they didn’t slow the advance. Soon, the Germans held the far bank.

Bridgeheads

Despite some small pockets of desperate resistance, the French facing Sedan across the Meuse were soon overcome. Guderian gave the order for his lighter armored units to start crossing and reinforce the bridgehead.

German troops seized the heights above the river and pursued the retreating French. They punched clean through both lines of defenses, smashing open the formations the French had relied upon. On the left, they didn’t have artillery support and so struggled with the crossing, but still made it.

By the end of the day, Guderian held a bridgehead three miles (almost five kilometers) wide and four to six miles (six to nine kilometers) deep.

Further north, Rommel was making a similar crossing at Dinant, but stiffer French resistance slowed him down and he took a smaller bridgehead. Guderian’s was the triumph of the day.

Breakthrough

The 14th of May proved as critical as the 13th, though for quite different reasons.

Having established a bridgehead, Guderian set about reinforcing it. A pontoon bridge allowed the Panzer armored divisions to flow across the Meuse and join the forces on the French side.

The French made attempts to counter-attack with their own armor in the morning, but this thrust was delayed. By the time it got going, the Germans were ready to tackle it. The French counter-attack was caught in the flank by newly arrived German tanks and soundly destroyed.

Excessive caution characterized the French response. When the 3rd Armored Division, an impressive French force, arrived in the area, it was diverted away from a counter-attack at Sedan to form a defensive line. Guderian’s opponents were giving him the time he needed to prepare another thrust.

Exploiting the Opportunity

On the 15th, the Germans hit the French hard. Rommel and Reinhardt, who sat between him and Guderian, both made great advances heading past the Meuse and deeper into France. Rommel’s forces fought the first major tank-versus-tank battle of the campaign at Philippeville, where they fought on the move, keeping up their momentum to ensure the collapse of the French lines.

Guderian had a harder time of it. Securing his flank meant bitter fighting for the heights around Stonne. But this didn’t stop him advancing with his other troops.

By the end of the 16th of May, Guderian was 55 miles (88 kilometers) past Sedan and still moving. It was an incredible achievement in which he had secured the German left flank even as he, Rommel, and Reinhardt smashed a hole through the French lines.

Aftermath

The breakthrough at Sedan was the ruin of the Allied campaign in France. Guderian and Rommel raced for the Channel coast, with Guderian the first to arrive on the 20th of May. The Allied armies were shattered, demoralized, and split in two.

The fall of France was assured.