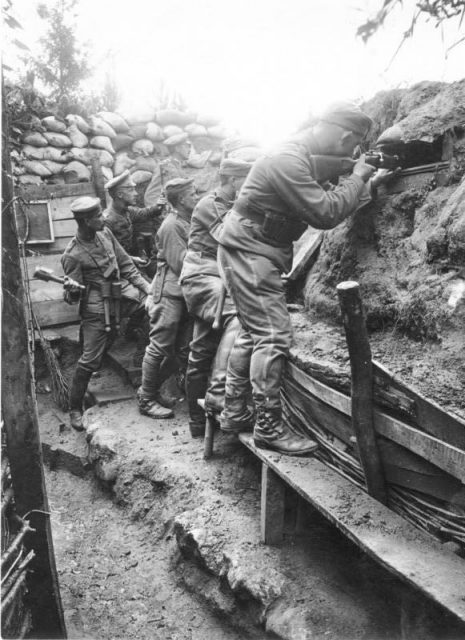

Stormtroops would be equipped with satchels full of grenades, making virtually every man a walking arsenal.

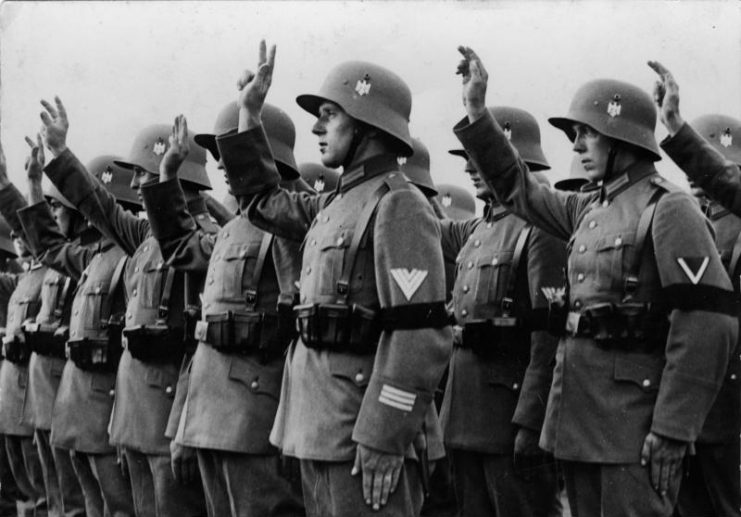

In recent years, the term “stormtrooper” has come to mean something out of the science fiction world of Star Wars. It wasn’t an accident that George Lucas used the term. Before his movies, the word was used to describe the men of the SS, Hitler’s fanatical bodyguards.

But it was also no accident that Hitler and others used the word to describe his elite unit. In the front lines of WWI in 1918, where Hitler was a runner in the trenches, the new and innovative German infantry units dubbed “Sturmtruppen” led the last great German offensive of the war.

In the Romantic Era of the late 19th century that saw Germany become a united nation, the word “storm” was popular. It denoted power and impending doom. Nothing could have described the German troops of 1918 better, but the truth is, these specially trained German soldiers were not the only “stormtroops” of the war.

Italy had its “Arditi” – “the Ardent Ones,” and elements of the British Lancashires actually referred to themselves as “stormtroops” and underwent specialized small-unit training towards the end of the war, as a way to (hopefully) break the log-jam of trench warfare, which was not only costly but also kept each side from its larger objectives. Other nations such as Canada and Austria experimented with similar ideas.

The impetus in developing new infantry tactics came from the bloody stalemate of trench warfare and the new weapons of war which made it necessary, primarily the machine-gun. It is an axiom of warfare that armies tend to fight their next war the way they fought their last.

Though infantry weapons had become much more deadly in the late 18th century, men still organized themselves on the battlefield as if they were on the parade ground. This was primarily to increase firepower and casualties on the enemy, but also was because many of their officers were not capable of maneuvering troops freely outside of formation.

The result? The hundreds of thousands of men cut down in rows by machine guns.

German Military Innovation

This went on for years, but behind the scenes, even in 1915, the Germans were working on training specialized units in new tactics and weapons. In this, the Germans had a significant advantage and head start over their rivals: their command structure.

Though the stereotype of the German soldier is one that rigidly obeyed orders like an automaton, this in many ways was far from the truth. Long before other nations developed the modern infantry tactics of today and the type of command and control necessary to coordinate them, the Germans were innovating them.

Basically speaking, years before most of the other great powers, the German army trained each man, from the bottom to the very top, in the job of the man one rung higher than him on the ladder.

For example, should a sergeant fall on the field, the corporal under him would have not only trained as a corporal but would have known the sergeant’s job as well, and thus could fill his role. The sergeant would have known the lieutenant’s job, etc., up to the top.

This sounds completely mundane today, but in 1914-1918 this was pretty unheard of – you didn’t learn the job of the man above you until you had earned it.

The Germans’ departure from that mindset meant that in the chaos of battle, the death of one man might not stop an attack in its tracks. Of course, this is an oversimplification, but the German Army showed a great deal more flexibility in this regard than any of its foes.

Another factor that contributed to the development of stormtroop tactics in 1918 was another idea that seems to run counter to the image of the German/Prussian military man as a mindless military machine.

From the top down, officers and men were given objectives, and perhaps a framework to work within, but within each planning stage, all the way down to squad level, officers and men were (generally) responsible for working out a plan at their level for achieving their objective.

For example, a captain commanding a company might be given the assignment of capturing a small town. How he did this was up to him – given the equipment allotted to him, timetable, etc. Typically, he would assign each platoon commander an objective and they would work out with their sergeants (and they with their corporals, and so on) how they would go about the attack.

In many of the other armies of 1914, generals and colonels with no knowledge of the objective would plan out the assault for company commanders and very little deviation was allowed. Today the German idea does not sound revolutionary at all, but back then it was, and it laid the foundation for modern infantry tactics.

Evolution of the “Sturmtruppen”

In the spring of 1915, a German unit was developed under the name “Sturmabteilung” (“Assault Section”). Yes, this was the same name given to Hitler’s early “Brownshirts” or “SA,” many of whom had served in these type of units during the war. Later, as the unit grew, it was referred to as a “Sturmbataillon” and the men within it as “Sturmtruppen.”

In charge of training this group of men was Captain Willi Rohr, who had been in the army since he was 14 years old. He had come up through the ranks and had also served in a specialized “Jäger,” or “Hunter,” division.

The Jäger were specialized troops that operated in forests and woods, and many of the men within them had been gamekeepers, hunters, and even poachers. They had different and camouflaged uniforms before most of the rest of the German Army did, and had a strong esprit de corps.

They were also given a much greater degree of autonomy than many other troops since they would be out of the reach of communications for days or weeks at a time. The wooded areas in which they drilled and were deployed also called for a more flexible formation strategy. All of this evolved into the first stormtrooper units.

Among the first changes that Rohr made were to the units’ field artillery. Many German units had organic artillery within them, both of relatively small caliber: 37mm and a heavier 3-inch (7.5 cm) support gun. Rohr and his men reduced the weight of both of these weapons, making them much more portable.

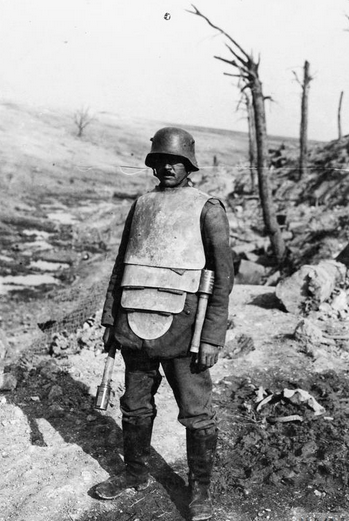

Rohr also changed the footwear of the men – instead of the traditional jackboot we’re all familiar with, he equipped them with more resilient and flexible Austrian mountain boots, which were lighter and quieter as well. Different camouflage patterns were developed and the uniform itself was equipped with elbow and knee patches made of cloth and leather to help with crawling and to prevent injury.

The most obvious changes came in the form of weaponry. First and foremost, Rohr reached back into the past, using the old grenadiers of the Prussian Army as a model. Like these men, his stormtroops would be equipped with satchels full of grenades, making virtually every man a walking arsenal.

The standard German infantry rifle, the famous Mauser 98k, was made lighter and shorter for easy movement and firing. Later in the war, the stormtroops were the first to receive sub-machine guns, those weapons whose development was owed to the need to clear trenches. Shotguns were also deployed.

Rohr initially developed body-armor, but the materials of the time were too heavy and impeded movement, and fast movement combined with overwhelming violence was key to the stormtroops’ success. Other nations, particularly the Italians, did develop and used body armor.

One piece of equipment did stay and was eventually used by the entire German army – the coal scuttle helmet, which provided much greater protection than the spiked “Pickelhaube” helmet of the wars’ first years.

Stormtroop tactics in WWI

Rohr, and others such as future legend Erwin Rommel, developed infiltration tactics designed to surprise and overwhelm the enemy. They realized that the hours-long artillery bombardments that took place all along the line didn’t inflict the desired casualties, but did alert the enemy of a pending attack.

Accordingly, Rohr and the subsequent stormtroop units either gave up the barrage entirely, or focused a short and intense barrage on the one part of the line they were planning to assault. Sometimes this was a ruse, and the units used the noise down the line to cover their movements while attacking elsewhere.

As in WWII 20-some years later, the men of the stormtroops attempted to seize the weakest part of the enemy line, break through, and assault the rest of the enemy position from the rear. The men would be right behind the barrage, which became known as a “rolling barrage” when the British used the tactic in the last part of the war.

Before the enemy could recover their senses, the stormtroops were on them, using their grenades, shotguns, machine-guns and small field artillery under direct fire. Once in the trenches, the men of the stormtroops used their own brutal and primitive armament: clubs with nails, medieval spiked maces, trench knives with grooves and skull crackers, and of course, the sharpened shovel.

In the spring of 1918, General Ludendorff launched the last German offensive of the war. Leading the way were the stormtroops, many of whom infiltrated enemy lines before the main attacks. For the first days of the offensive, they caused shock and panic among the Allies, driving them miles from the starting point.

Read another story from us: Brandenburgers – The Nazi Menace Behind Enemy Lines

However, as the offensive continued, attrition and exhaustion took their toll on the men of Sturmtruppen and many of them simply collapsed. In more than one case, deprived German troops, overrunning French supply depots, filled themselves with bread, cheese, and gallons of wine. The result? A lot of German POW’s.

The German Offensive of 1918 failed for a number of reasons, but the tactics of the stormtroops live on today on almost every battlefield in the world.