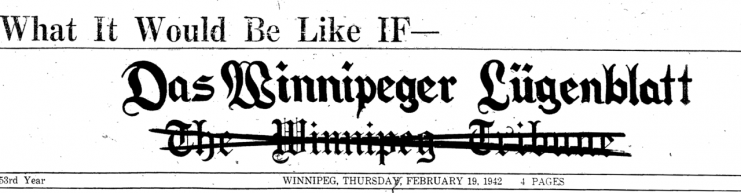

There was a day when the Germans invaded Winnipeg. That day was February 19, 1942, and it was a training scenario called “If Day.”

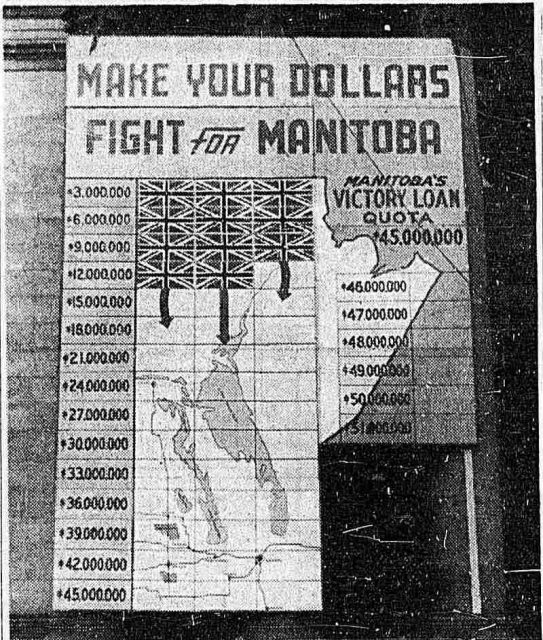

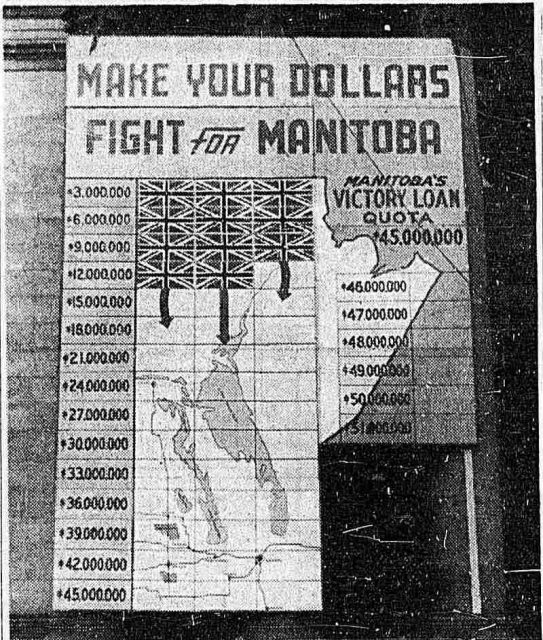

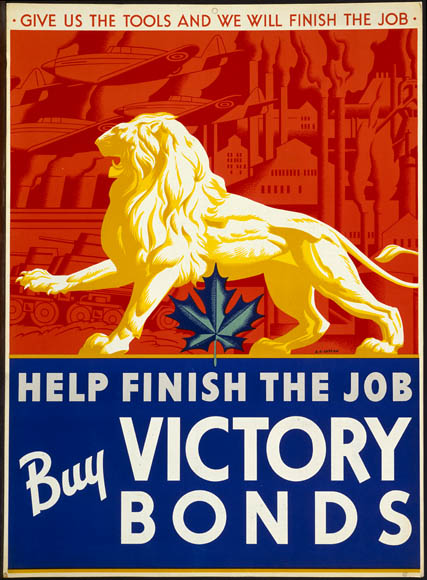

The event was designed as part of a bond-selling effort. City officials thought that if the population could feel the effects of a faraway war it would help them selling 45 million Canadian dollars’ worth of bonds in the Manitoba area.

To prevent mass hysteria similar to the fictional War of the Worlds broadcast a few years earlier, officials advertised the “invasion” on the radio and in print media in the days leading up to the event. They even included ads in nearby Minnesota to prevent panic across the border.

The simulation used 3,500 reserve units and volunteers, making it the largest exercise in that region up to that point. The reserve units played the defenders while the volunteers used rented Hollywood costumes to portray the Nazis.

The invasion started at 5:30 am with the radio announcer being replaced on air by a Nazi information officer. The reserve units and volunteers mustered shortly thereafter. The radio played German-themed music with snippets of Hitler’s speeches throughout the rest of the day.

Mock air raid sirens sounded at 7 am, and the volunteers entered the outskirts of the city minutes later. The activated reserve soldiers formed a defensive perimeter around the industrial and downtown areas of the city.

The firefight included large scale troop movements patterned after the French mobilization of Paris during World War I. The defenders placed tanks at road and rail junctions.

Fighter planes were repainted to look like German aircraft while defenders fired blanks from several dozen anti-aircraft guns.

Coal dust exploded by dynamite was used to simulate the destruction of bridges.

The first mock casualty happened at 8 am, shortly after the defenders followed their script and fell back to a tighter position in the center of the city.

Mock dressing stations treated the fake casualties. There were also a couple of real injuries with a soldier spraining his ankle and a woman cutting her finger while cooking.

By 9:30 am, the defenders surrendered and withdrew to a predetermined position downtown. The pretend invaders drove a tank down the main street, which was renamed Hitlerstrasse.

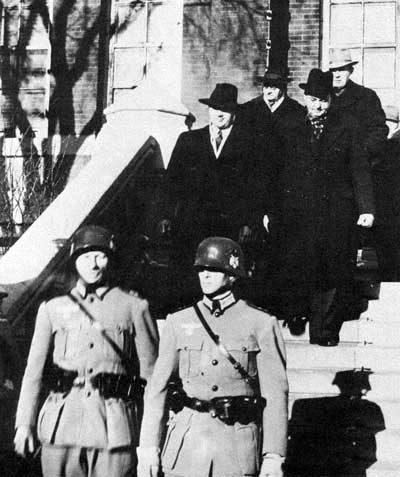

The “enemy” interned captured politicians like the Premier, John Bracken, and several members of his cabinet. They also arrested the mayor and the Lt. Governor.

The Canadian flag at the fort was lowered and replaced with one displaying a swastika.

Notices were posted around town about new rules. If priests objected to such notes being pinned on the doors of churches, they were arrested.

The newspapers ran fake articles that were mostly in German or posted jokes that the people were commanded to laugh at. The Winnipeg Free Press ran a story detailing the Nazi devastation of the area.

The high school students had to read lesson content formed by German propaganda. At least one elementary school principal was replaced by a Nazi instructor.

The fake German soldiers seized Buffalo coats from the local police station whose commander escaped arrest due to being out for lunch. They burned books outside of local libraries. (The books were pre-selected texts that were already damaged and set to be replaced.)

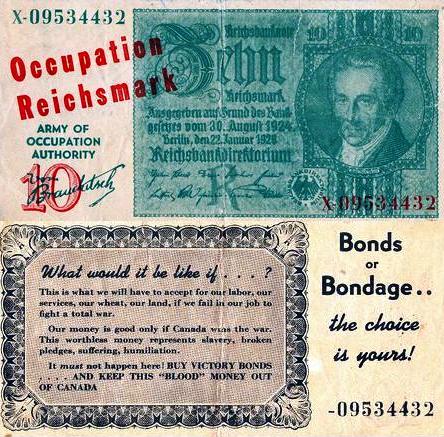

Fake German currency was also issued. Even nearby towns were involved, with citizens being confronted in the streets by “Nazi” soldiers.

The event ended at 5:30 pm that day with a symbolic release of prisoners, speeches from civic leaders, and a parade down Main Street advertising the Victory Bonds.

The event was a wild success. It received worldwide media coverage with outlets as far away as New Zealand and the BBC. Life Magazine even did a photo spread.

The organizers raised 3.2 million dollars in a single day, which was a record for the city. By the end of the month, they had blown away their goal of 45 million by raising 60 million dollars.

Overall, the event raised 2 billion dollars’ worth of bond sales across the country. After that, other cities did similar but smaller events throughout the war.

A documentary in 2006 used actual newsreel footage from the original event.

Providing a small taste of German occupation was important for those far from the front. But it’s important to remember that it was a small taste of what so many French, Nordic, and Polish people endured for many years.