During the Second World War, hundreds of thousands of Allied combatants spent time as captives of the Germans. From Polish soldiers captured on the first day of the war to airmen shot down during the last bombing campaigns, they experienced the dubious welcome of prisoner of war (POW) camps.

Cold and Hungry

The overall experience of life in a prison camp was low level, persistent discomfort. This went well beyond the loss of freedom.

Germany’s resources were limited and prisoners of war weren’t high priority recipients of such scarce resources. Though prison camps provided some shelter, they didn’t offer great protection against the weather, particularly the cold of winter.

Food became a huge preoccupation for prisoners. They were meant to receive 1,900 calories each day, the same as a non-working German civilian, but got something closer to 1,500 calories. Most PoWs lost at least 40 pounds (18 kilograms) in weight. Dreams of food became a major topic of conversation around the camps.

Staying Entertained

Men sought to take their minds off their situation. Some took the opportunity to study. They could gain qualifications through correspondence courses, preparing them for civilian life upon release.

Others put on theatrical productions. At Stalag Luft III, theater seats were made from Red Cross boxes and footlight reflectors from biscuit tins.

Female impersonators played a prominent part in these productions as well as in improvised tea dances. For a moment, men could pretend that they were back home and that there were still women in their lives.

Out and About

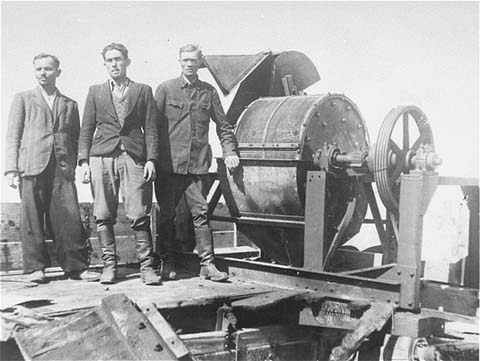

Some men met local women when they went out of the camps on work parties. Sent out under guard for up to a week at a time, they cleared the damage caused by Allied bombing raids.

Using coffee and cigarettes from their aid packages, these workers were often able to bribe their guards to let them get away at night. Those same treasures, as well as American chocolate, won them the favor of local women in a country suffering from the economic blockade. Some men fell in love and deserted the work parties, an action which could bring dire punishment from the authorities.

National Differences

Those sent out on work parties were mostly Americans, Britons, and Canadians. Russian captives had a far harder time.

German racism against Slavs and political hatred of Communism led to appalling cruelty. Guards treated Russian prisoners as less than human, beating and half-starving them. Even when they were in the same camps as other nationalities, they were treated differently.

With characteristic determination, the Russians struggled to survive and to show their own strength. On several occasions, they captured and killed guard dogs at night, ate the meat, and left the pelts spread out – a sign of defiance against their oppressors.

American and British troops received similar treatment to each other but often responded in different ways. The British national obsession with the stoic “stiff upper lip” led many to knuckle down, resist complaining, and try to survive through shared discipline.

The Americans, coming from a wealthier nation geographically distant from the war, were more likely to complain about their conditions and how they had come to be there. Their officers faced a tougher job trying to assert discipline.

How Long?

Discipline and structure were vital to keep the men emotionally healthy.

Until the late stages of the war, captives faced great uncertainty over how long they would be held. Their lives were out of their control. They could be trapped like this for a decade or more.

Discipline helped to provide a sense of purpose and something familiar. By reasserting the hierarchies and habits of military life, officers kept themselves and their men active and sane, preventing a descent into despair and depression.

Changing Sides

Some men found purpose in a very different way: by changing sides.

For a few, this was a natural step. Any followers of the anti-communist movements back home now found themselves in a country more sympathetic to their beliefs. Such men were easily signed up to international units within the Waffen SS, turning against their countries in favor of their beliefs.

Many more were drawn into these units following encounters with women on work details. Promised sexual favors for changing sides or threatened with punishment from the authorities for the favors they had received, they reluctantly signed up to fight for their enemies.

Facing the Holocaust

POWs seldom found themselves on the sharp end of Germany’s worst prison camps, those used in the Holocaust. But some saw them in action and a brave few even helped victims to escape.

Captured during the retreat to Dunkirk in 1940, Charles Coward became Red Cross liaison at Stalag 8B, near Auschwitz. There, he used his position to rescue over 400 Jews.

He obtained the identity papers of non-Jewish prisoners who had died in captivity, then swapped their bodies for living Jews during the march to the gas chambers. The people he rescued lived on using the stolen papers.

Another group of British POWs from Stalag 20B found a fugitive Jew while on a work detail in January 1945. They hid her, fed her, clothed her, and kept her alive until the war swept past and she safely moved on.

Escape

Many prisoners spent their time trying to escape. Even if they didn’t make it home, they hoped to keep the Germans occupied with their efforts, draining enemy resources.

Escape operations were usually coordinated by a single officer in each camp, to make sure that escapees didn’t get in the way of each other’s plans. Ingenious efforts were made to fake documents, German uniforms, and civilian clothes for escapees, as well as to equip them with escape tools.

The British escape organization MI9 and its American counterpart MIS-X helped them, smuggling in tools, information, and components for radios to keep them in contact with home.

Read another story from us: War Crime? Utah Camp Guard Opened Fire on German POWs After War was Over

Though many POWs spent years suffering from hunger and maltreatment in the prison camps, few were broken by the experience. Their strength was shown in their efforts to help themselves as well as others to thrive and to escape against the odds.