Imagine being the general of a conglomerate army of 1,300 men, faced with the prospect of leading an offensive attack against a fortified position defended by 2,500 men. Sounds almost impossible, right?

This exact situation occurred along the Detroit River during the War of 1812, and the conquest of Detroit by the British and Native Americans is an amazing tale of how stellar leadership, a dose of pure good fortune, and brilliant use of psychological warfare converged to enable their much smaller army to achieve an ambitious and daunting objective–without losing a single man to enemy fire.

Background

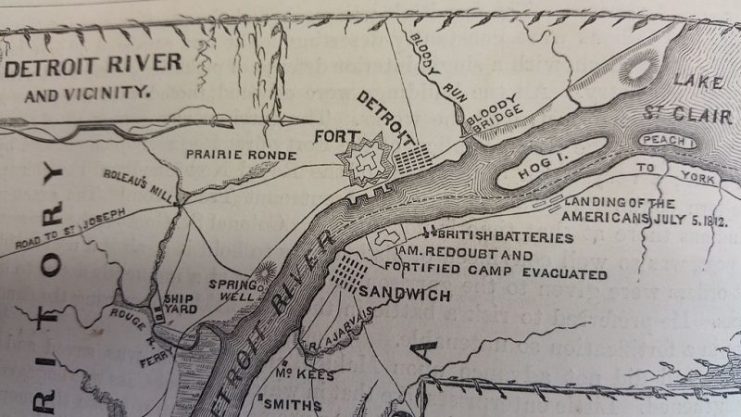

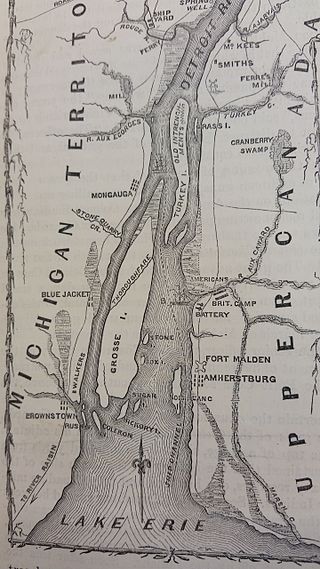

In July and August of 1812, British, Native American, and American forces all converged on the Detroit River near Lake Erie. The American army held the west side of the river, at Fort Detroit. The British and Native Americans gathered at Fort Amherstburg, on the east side of the river. Both sides had the goal of crossing the river and routing the enemy from their position.

The Americans made the first move by crossing the river, occupying a small settlement, and persuading some Canadians to join their side; but then they hastily withdrew without pressing on to attack Fort Amherstburg, even though the fort was vulnerable and the Americans knew it.

Leadership

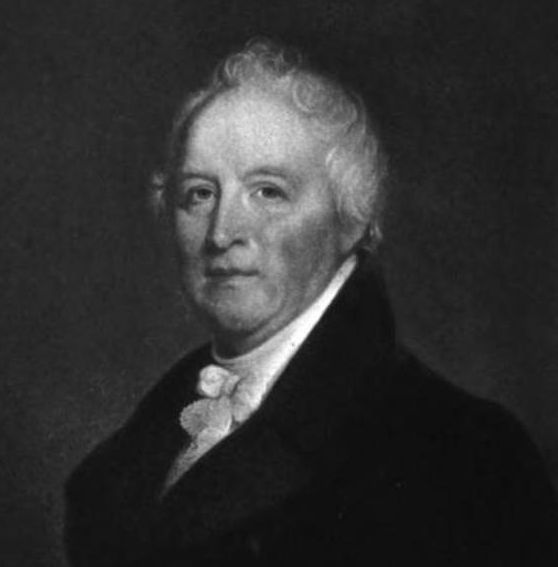

This preliminary incident illustrates the overly cautious nature of the American general, William Hull, an elderly Revolutionary War veteran who had to be persuaded to take up arms again by President James Madison. Hull may have excelled during the Revolution, but his bravery did not extend to fighting Native Americans in the wilderness.

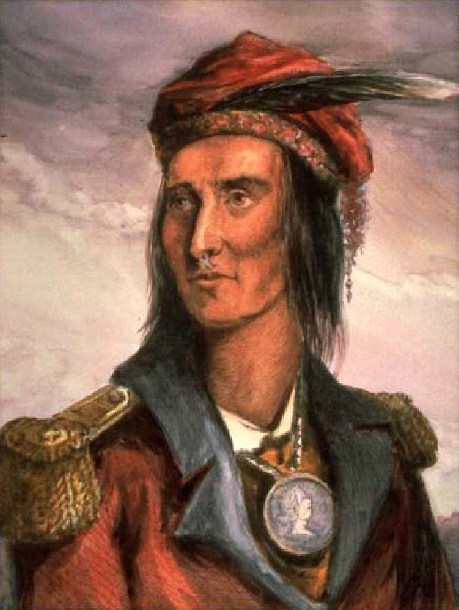

To be fair to Hull, his concerns about “Indian massacres” were not without precedence or substance, and he was unaware that the local Shawnee Nation chief, Tecumseh, was an honorable man who personally ensured his own warriors treated captured Americans humanely.

All Hull knew was that he was “out in nowhere,” where the roads were few and bad, the British controlled all water routes, and his lengthy and uncertain supply lines were periodically ambushed by the Natives lurking in the woods. He also had a fort full of helpless civilians to protect, including his own daughter and grandchildren. When Fort Michilimackinac fell to the British, Hull was positive that the Native tribes further north would swoop down upon Detroit next.

Hull also expected more British soldiers to show up at any moment, hence his decision to cancel the attack against Fort Amherstburg. All of these factors added up to make Hull a nervous wreck; and so it was, that the American army found itself with superior numbers and probably an easily attainable objective of pushing the British out of Fort Amherstburg, but with a general who had no heart to leave the relative safety of Fort Detroit and go after it.

In complete contrast, the British and Native American forces were commanded by younger, more ambitious men who proved to be masterminds of military strategy.

Sir Isaac Brock, governor of Upper Canada, advocated assuming the offensive against the Americans in the “Northwest Territory”, which directly aligned him with Tecumseh, who had already been fighting the Americans in the vicinity for the past two years.

Although neither the British government nor Brock’s immediate superior (Sir George Prevost, the governor of Lower Canada) shared Brock’s views, they left him plenty of leeway to pursue his aims, so he hastened to Fort Amherstburg to meet with Tecumseh.

Delighted by Brock’s bold willingness to attack Detroit, Tecumseh immediately pulled out his hunting knife to draw a map of the area on a piece of birch bark, cementing their military collaboration right then and there.

In Tecumseh, Brock found an influential ally who nearly doubled his available manpower and who was intimately familiar with the area. Even though the combined British and Native American forces were still far outnumbered by the Americans, they had a huge advantage in not one, but two leaders who possessed the desire, ability, and vision to creatively craft a plan for success.

Good luck

As fortune would have it for the British, they had seized General Hull’s baggage, including all of his private papers, before Hull even reached Detroit. Therefore they had a full and accurate picture of American strengths, weaknesses, and objectives. Brock lost no time acquainting himself with Hull’s personal apprehensions, conveniently spelled out by Hull himself in black and white.

Psychological warfare

As the British and Native Americans prepared for a direct assault on Detroit, Brock set about to exploit the information gleaned from the captured papers in order to further rattle Hull’s nerves. First, the British began bombarding Detroit from afar, using gunboats on the river and gun batteries on the opposite shore.

Then they crossed the river, to where the Americans could see some of them. Brock had 700 soldiers, 400 of whom were militia, but he had the militia also wear red coats so that from a distance, they appeared to be British “Regular” army soldiers.

Militia were not so greatly feared, as they were generally undisciplined and unreliable; all too often they outright fled once the firing got hot. Regulars, on the other hand, were a force to be reckoned with. Considering that Hull had many frontier volunteers in his own army, pitting them against a large number of Regulars was an unfavorable prospect.

That evening, Brock and Tecumseh played another psychological warfare card: Tecumseh’s 600 warriors crossed the Detroit River, and all night long Hull could hear them calling to each other, imitating wild animals, and deliberately creating the impression of a barely restrained horde of savages who were about to swoop in and massacre the helpless civilians in the fort. The image of Native Americans as wild savages is taboo today, but two hundred years ago, Brock and Tecumseh exaggerated it to very great advantage.

Not only could the Americans see all those red coats and hear the Native Americans, but to pile on to Hull’s woes, Brock also arranged for a fake courier to “stray” into American lines so that when he was captured and searched, Hull would end up with an equally fake document that mentioned the imminent arrival of 5,000 more Native American warriors.

Talk about added pressure! Hull would think that even if he fended off the attack that day, he would soon be surrounded and outnumbered by the Natives he so dreaded.

As if all of those factors weren’t enough to assault Hull from all sides and render him paralyzed with anxiety and indecision, Brock had sent over a missive that would be the cherry on top—a demand for surrender that explicitly said that should there be a battle, Brock would have no control over the actions of the natives.

Hull initially rejected Brock’s demand, but then dissolved into a state of complete demoralization, quite literally sitting on the ground and silently stuffing quid after quid of tobacco into his mouth, while the juice dribbled down his chin. As time dragged by and Hull made no effort to direct his army to do anything, some of his men became so frustrated by his inaction that they discussed mutiny—but they did not take action quickly enough.

Succumbing to the strain of Brock and Tecumseh’s trickery on top of all his other worries, Hull chose to surrender rather than even attempt to fight.

The fall of Detroit was a costly “lesson learned” for the United States of the foolishness of sending an army to war without a courageous and focused man to command it.

Read another story from us: The Pressing of American Seamen And The War of 1812

The British and Native Americans may have had poor odds regarding the numbers of their fighting forces, but the scales were tipped completely in their direction when it came to having a solid plan and accurate information on their enemy, which their more audacious leadership exploited to pull off a brilliant triumph of psychological warfare that author Harry L. Coles described as “one of the most glorious victories in British military annals” and simultaneously as “one of the most disgraceful episodes in the military history of the United States.”