Using insects – primarily maggots – to treat burns and wounds is a recognized, valid therapy. It is still used today to “debride” (clean) everything from necrotic tissue to severe burns.

This method may have a repellent “yuck factor” working against it, but using critters to clean and heal wounds has been part of legitimate medicine for centuries.

Even when doctors didn’t know that they were helping patients, like during the years of the American Civil War (1861 – 1865), bugs have been doing their bit to increase survival rates of soldiers left wounded in the field.

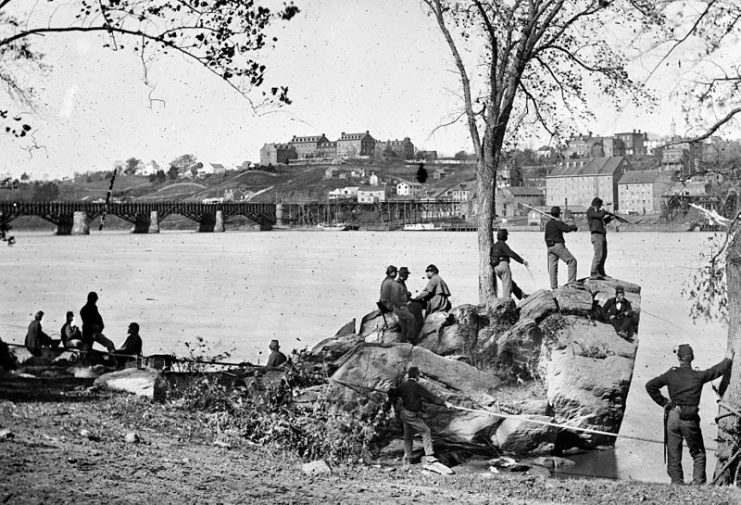

Civil War soldiers fell prey to much more than enemy fire. Inadequate medical care at the time meant that many soldiers’ wounds went untreated for days. They were often left in mud and swamps waiting for a medic to retrieve them and treat their injuries.

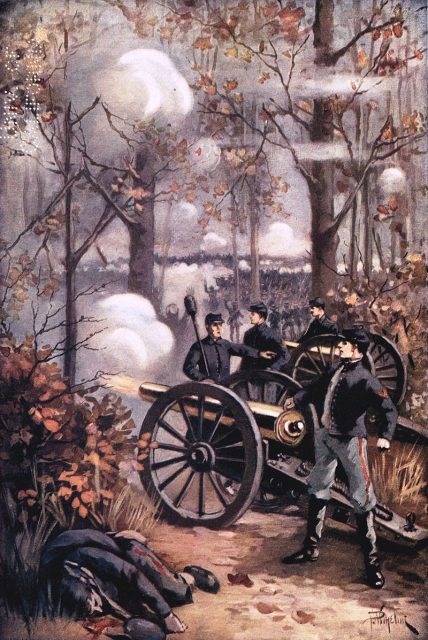

One battle in particular, near Shiloh, Tennessee, was spectacularly gruesome. General Ulysses S. Grant and his Union soldiers outnumbered Confederate troops by more than 10,000 men, so the Rebels were soon retreating to Corinth, Mississippi.

It was a horrifically bloody battle that saw 3,000 men die in combat. Another 16,000 from both sides were left critically injured and stranded on the field.

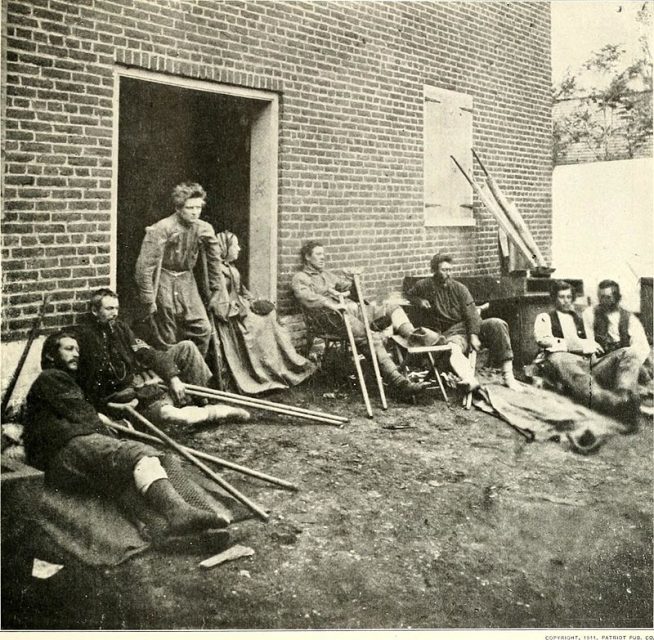

Not surprisingly, soldiers weren’t just dying from gunshot wounds but were dying slow, painful deaths from infections like gangrene. Antibiotics were not yet a part of medicine, so most doctors simply amputated a man’s limbs to stop infection from spreading.

But at the Battle of Shiloh, where many men lay in mud and moist earth for days before getting treatment, something very odd was occurring.

Those suffering from gaping wounds began noticing that their wounds looked unusually bright, almost glowing. This feature was so striking that the men named it “Angel’s Glow.” They also noticed that those wounds blessed with Angel’s Glow seemed to heal much more quickly than others.

One hundred and forty years later, a young man, Bill Martin, read about this phenomenon when he and his family visited the Shiloh battlefield. His mother was a microbiologist so he asked her what could account for Angel’s Glow.

She reacted as any good mother and scientist would: she told him to conduct an experiment to find out.

Martin and a friend began to study the environment and weather patterns around Shiloh. They soon discovered that the bacteria, called “P luminescens,” which had been found in soldiers’ wounds came from the intestines of Nematodes, or ringworms.

Initially, the bacteria dig deep into the insect’s larvae and stay in its blood vessels. However, the Nematodes eventually regurgitate the bacteria inside them, and the bacteria give off a soft glow. The biological purpose of the light is not yet understood by modern science.

From his experiments, Martin realized that the soil and weather conditions at Shiloh were ripe for the bacteria to thrive. Usually, the bacteria can’t survive a human’s normal body temperature which is too warm. But in the case of the Civil War soldiers, the men were often left lying in chilly, damp conditions, so their body temperatures dropped just enough to keep this helpful bacteria from dying.

Read another story from us: Youngest Combat Casualty in the Civil War Fell at Antietam

It’s not all good news, however. A consequence of the nematodes infiltrating the men’s wounds was that it often caused persistent ulcers and other gastrointestinal side effects.

Still, those with Angel’s Glow lived to tell the tale of their bright, shining wounds, even if they didn’t understand the true link between that bioluminescence and their survival.