In the latter half of the 15th century, there was a superpower in Europe. It wasn’t France, and it wasn’t England. Spain would not rise to world prominence until the voyages of Columbus in 1492. By that time, this kingdom was already in decline, involved in wars of succession since the death of the king that had held his domain together for thirty-two years.

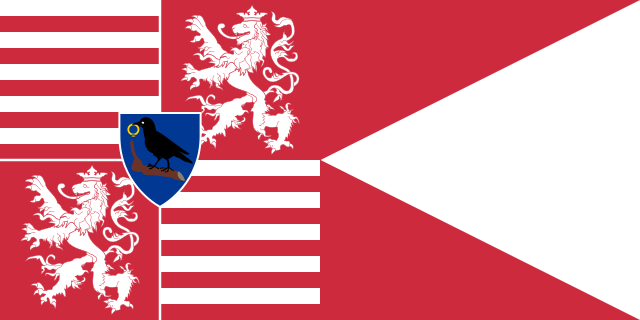

The kingdom was Hungary, and its king was Hunyadi Matyas, or Matthias Hunyadi, Matthias I, or as he is most commonly known – as Matthias Corvinus, the Raven King. Corvus is the genus of the raven, and the Corvinii an ancient Roman family.

Matthias’ ancestor and founder of the Hunyadi dynasty, John/Istvan supposedly traced his family back to this clan of the Roman aristocracy. A raven with a golden ring in its mouth was the symbol of the dynasty and was present in its many coats of arms and other emblems.

This article is about one part of Matthias’ powerful army, but before we get to that, here are a couple of things that you should know about the Raven King. Firstly, he came to the throne at age fifteen. Officially his kingdom was to be administered by a regent/guardian, his uncle Michael, but within two weeks, Matthias has asserted both his power and his ability and it was he who ruled from that moment forward.

Second, Matthias was both extremely well-read and intelligent, and over the course of his life, he built the greatest library in Europe outside of Italy, the Biblioteca Corviniana, which at its height included anywhere between four and five thousand works, many of them ancient Greek and Roman classics.

Matthias was an adherent of the spirit of the Renaissance of Italy, and can be said to be the first “Renaissance” king outside of the Italian peninsula. Unfortunately for the world many of these works were destroyed by the Ottomans after Matthias’ death.

Third, the Raven King faced enemies on all sides, and most of the time defeated them. Through military strength, guile, personal bravery (Matthias fought and was wounded on at least two occasions during his reign), and his shrewd judge of military ability which allowed him to place skilled men at the head of his armies in the field – Matthias faced the Holy Roman Emperor, the Ottomans, Poles, Romanians, Saxons, Czechs, Serbs…the list goes on.

Even more amazing is that the nature of both the time, politics, geography and demographics made it so that many of these groups that fought against him also at times fought with Matthias, sometimes against their own countrymen, sometimes with them. When Matthias died in 1490, the Kingdom of Hungary included parts of Poland, Saxony, Austria, Romania, Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, and Italy.

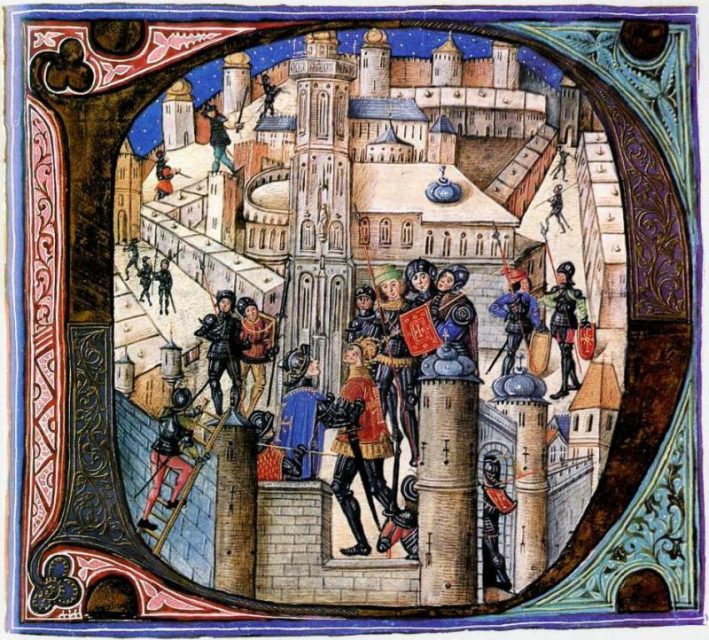

The backbone of Matthias’ military was called the “Black Army”. No one is entirely sure where the name came from. Some sources say it is likely from the black armor worn by its men. Others say that is nonsense, and that the name comes from a reference of the time – that “black” was another way of saying “tough” “hard” or “ruthless”.

At the time, only one other nation/kingdom had a standing professional army – France. The Black Army was perhaps twice the size or more of Louis XI’s force. At its height (historians use its passage through Vienna during a staged show of force in a parade) the Black Army numbered between 25,000 and 30,000 men.

Another thing that made the Black Army unique was who it was made up of. The army was a mercenary force. In one way, this was a good thing. For the price he was paying, Matthias ensured he was getting skilled men at arms, not peasant levies, as was much (but not all) of the rest of his army and those of his enemies.

Also a positive – many of these men had been in independent mercenary armies which raided and ravaged the borderlands of Matthias’ kingdom. By buying them, the king was killing two birds (probably ravens) with one stone: he gained men and stopped the raids.

On the negative side, mercenaries need to be paid and timely. And they are likely to switch loyalties if a better price is offered, which sometimes was. For the most part, Matthias overcame this problem in three main ways. First, he paid more, but to do this he had to tax more, which caused him serious problems throughout his reign.

Second, he treated his men and commanders well and gave them large shares of the spoils of war. Third, he was in many cases utterly ruthless and cruel when needed. There were occasions where men who rebelled against Matthias were forgiven and re-entered his service, but many did not – because they had been beheaded, tortured or torn apart.

You know Vlad Tepes, better known as “Vlad the Impaler” or “Vlad Dracula”? He was Matthias’ off again/on again vassal and Matthias had him locked up once and eventually was the instigator of his death. Matthias was tougher than Dracula. Now you have an idea.

It is recorded that in 1487, the Black Army consisted of 20,000 horsemen (heavy and light) and 8,000 infantry. One of the unique things about the army, and Matthias’ forces in general, was that they were some of the first Europeans equipped with firearms.

Twenty-five percent of the infantry in the Black Army had firearms. That’s 2,000 men, far more than any other army of the time.

By Matthias’ own account, his infantry and heavy cavalry worked together, the cavalry helping to prevent enemies from closing with the men on foot, and the infantry fighting behind walls of pavises, tall and broad semi-rectangular shields which were set up edge to edge to make a sort of movable fortress.

Both heavy cavalry and infantry required more men to carry their equipment, so during battle, these men/pages were able to secure the pavises and help to reload firearms.

Additionally, Matthias’ armies brought with them large numbers of wagons, not to carry supply (though they could if needed), but to form an early version of the “laager” – wagons used as defensive mobile barriers. Matthias’ army was a very early fore-runner of mobile armored warfare.

Matthias was a voracious reader, and a great admirer of Julius Caesar, and he used his light cavalry in much the same way as the Roman leader did – to harass the enemy, to scout, to raid and outflank.

While the heavy cavalry and infantry were engaged, his light infantry would harass the enemies flanks, lines of supply and any reinforcements entering the battlefield.

Matthias and the Black Army fought countless battles. Most, but not all, victories. The Black Army’s most famous victory came at the Battle of Breadfield in Transylvania (1479) where it was part of a multi-ethnic army of Europeans fighting a multi-ethnic army of the Ottoman Empire.

The battle seemed to be going the Ottomans’ way until the leader of the Black Army contingent, Pál Kinizsi, led his heavy cavalry and nine hundred Serb infantry on a fanatic charge into the Turkish center, which broke the Ottoman army.

It is estimated that Matthias’ army lost three thousand men that day. Turkish losses were much higher, and the battle dissuaded the Turks from attacking Matthias’ kingdom for some years.

At Matthias’ death in 1490, he made plain his desire that his illegitimate son John take the throne, but John was a drinker and a pleasure seeker with no talent for ruling, and in the wake of Matthias’ death, Hungary began a swift decline in power and prestige.

_______________________________________________________________________

Matthew Gaskill holds an MA in European History, and writes on a variety of topics from the Medieval World to WWII to genealogy and more. A former educator, he values curiosity and diligent research. He is the author of many best-selling Kindle works on Amazon and is currently working on a new book.