Desperate times call for desperate measures – a truth that has been repeatedly confirmed in the pages of world history.

During the Second World War, the UK found itself in difficulties due to the lack of steel for the production of aircraft carriers.

Geoffrey Pyke was a British journalist and inventor who worked as an adviser to Lord Mountbatten, the head of the Combined Operational Headquarters (COHQ). He proposed a solution to this problem which was simultaneously fantastic and insane.

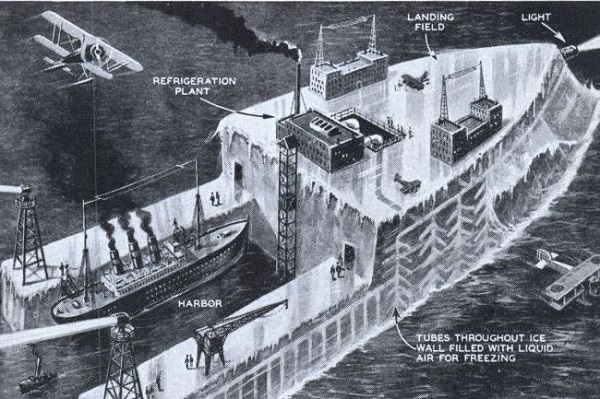

Pyke gained fame thanks to his penchant for original and outrageous ideas. He proposed to separate a large piece of iceberg, tow it into the ocean, then level the surface, and build the necessary structures for the aircraft and the crew.

This thought occurred to him while the British and Americans were talking about conducting special operations on the north coast of Europe. Knowing about the strength of Arctic ice, Pyke decided that the idea was worthy of consideration.

While in New York, Pyke sent his proposal through a diplomatic bag at COHQ with a note stating that no one except Mountbatten was allowed to open the package.

After reading the proposal, Mountbatten handed it to Churchill, who appreciated and approved the idea.

The project was named Habakkuk, which is probably a reference to one of the biblical books of the prophet Habakkuk (Old Testament).

It is worth noting that Pyke was not the first person who proposed the creation of a floating ice island in the ocean. In 1940, the idea of an ice island had been considered the Admiralty, but not taken seriously.

The German scientist, Dr. Gerke von Waldenburg, previously proposed this idea. In 1930, he had conducted some experiments on Lake Zurich.

According to the original idea of Pyke, the aircraft carrier was supposed to be about 600 meters long, almost 100 meters wide with a weight of more than 2,000,000 tons.

The runway of the Habakkuk was supposed to hold up to 150 fighters and bombers. All of it had to be protected by a multitude of anti-aircraft guns.

The ice-ship might be cheap to manufacture, but using ice had a significant drawback: it melts.

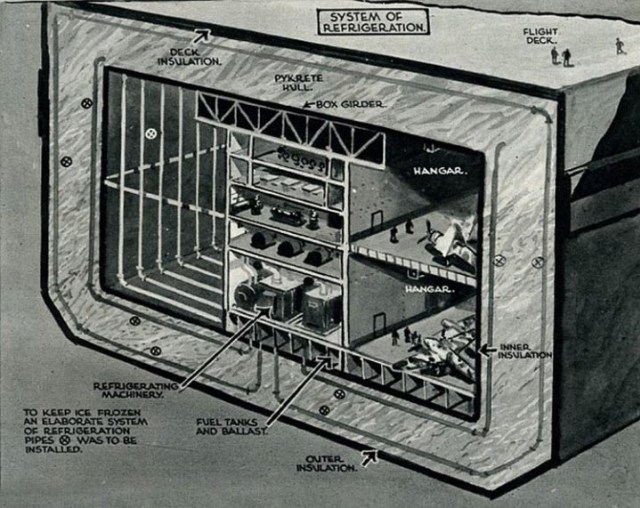

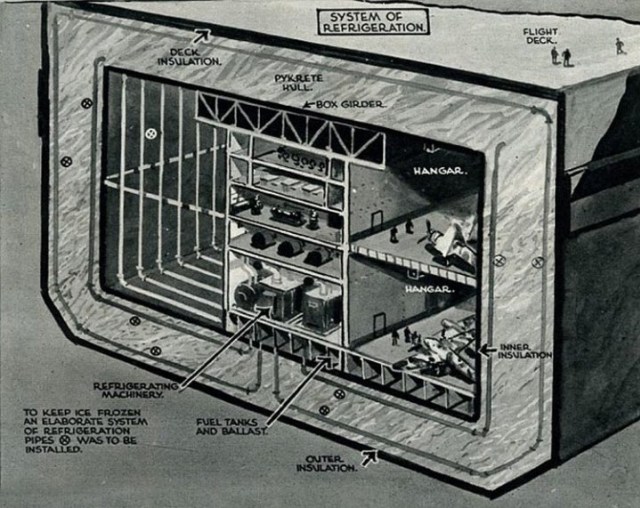

The problem with the melting of the glacier was solved by laying a network of ducts containing a refrigerant that was supposed to cool the iceberg.

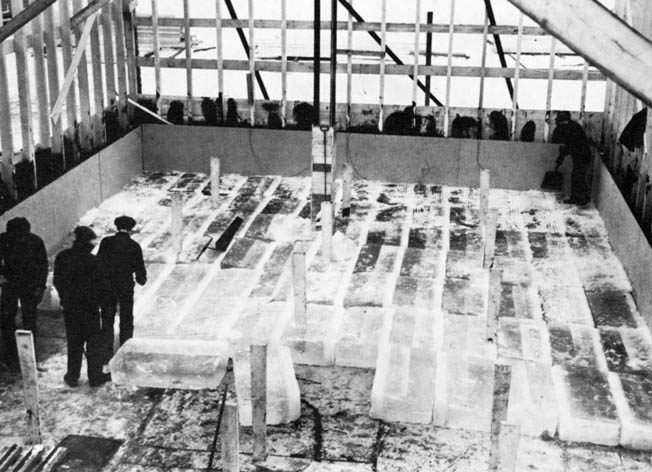

A prototype almost 18 meters long and weighing about 1000 tons was built in the Rocky Mountains of Canada, on the shore of Patricia Island. The cooling system was effective and maintained the prototype throughout the summer period.

However, other difficulties arose during the tests. Although ice is a solid material, it is extremely fragile. Put under the pressure of a strong weight, it can become deformed.

In addition, natural icebergs are not sufficiently stable. They can suddenly roll over. They also have too little surface above the water for a runway.

Given all these drawbacks, work on the project was temporarily suspended.

By chance, the scientists at the Polytechnic Institute of New York University made an interesting discovery.

They created a mixture of about 14 percent of sawdust and 86 percent of water then froze it. The resulting material turned out to be 14 times stronger than ordinary ice. The sawdust in this mixture prevented severe melting.

Furthermore, this mixture had a high resistance to compression and chipping. It was comparable in strength to concrete.

This composite material was developed by a government group and was named Pykrete (in honor of Geoffrey Pyke).

According to one legend, in 1942, Lord Mountbatten came to Churchill’s house and decided to hold a pykrete demonstration.

Using the bathroom, a piece of the material was placed in warm water. The two men stood for some time and observed how the ice refused to melt.

Another story has it that at the 1943 Quebec Conference, Lord Mountbatten brought in two blocks: one made of pykrete, and the other ice. He pulled out his pistol and fired once into each block.

The ice block shattered into pieces. But when Mountbatten fired into the block of pykrete, the bullet ricocheted, hitting the trouser leg of Admiral Ernest King before hitting the wall.

After successful testing of pykrete, work on the Habakkuk project was resumed.

According to the calculations, the construction of the ship would have required 300,000 tons of pulp, 35,000 tons of lumber, and about 10,000 tons of steel.

The cost of this project started out around £700,000, but over time increased to £2,500,000 because more steel was needed for more efficient insulation. There were also problems with handling and speed.

However, the biggest problem was the raw materials. Wood was a scarce material, and complex cooling installations were expensive. None of the Allies could afford such high spending.

In the end, the Habakkuk project was revised and then finally abandoned.

This decision was facilitated by the fact that the war was gradually turning in favor of the Allies through more traditional methods.

Read more articles from us – Could German Aircraft Carriers Won the Battle of the Atlantic?

British General Ismay described the project in his memoirs:

”The whole thing seemed completely fantastic, but the idea was not abandoned without a great deal of investigation. Various alternative methods of construction were then considered by the United States naval authorities, but in the end there was general agreement that carriers and auxiliary carriers would serve the same purpose more effectively.”