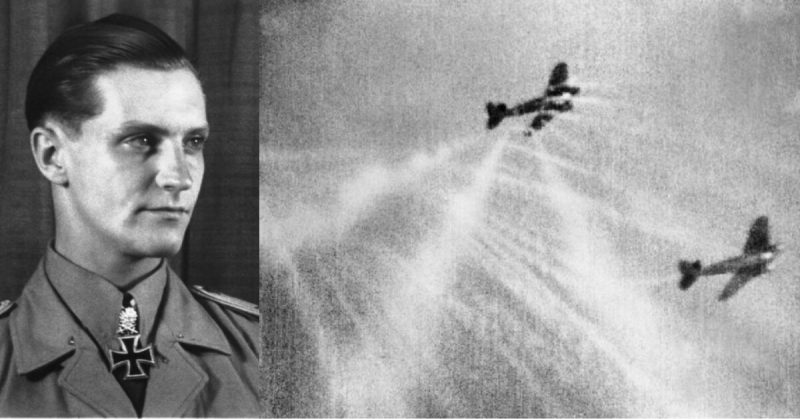

He was among Germany’s most accomplished Flying Aces during WWII – though he hated killing. His success was valuable propaganda for the Nazis – yet he was not a fan of the regime and even stood up to Hitler. Also, considering the number of planes he shot down, he had a rather unexpected death.

Hans-Joachim Marseille was born on December 13, 1919, in Berlin, Germany. His surname derived as he was descended of French Huguenots who fled France during its purge of that group.

His father, Siegfried, was an Army officer in WWI, and a General in the second world war. In 1941, he participated in the German invasion of Russia where he died. Before doing so, however, Siegfried introduced his son to a wild nightlife that was to be the younger man’s undoing.

As for Hans-Joachim Marseille, he was not expected to enter the military. As a child, he had been rather sickly and almost died from influenza. Spoiled and pampered because of that, he never learned to respect authority and developed a reputation as a lazy, rebellious, and troublesome student.

He joined the Luftwaffe (German Airforce) on November 7, 1938. During one cross-country flight, he landed in a field to relieve himself. He took off just as a group of farmers arrived, blasting them away with his slipstream. Upset, they called the authorities, causing him to be suspended.

This and many other such incidents held him back while his colleagues graduated and attained rank. On November 1, 1939, Marseille was posted to the 5th fighter pilot school. To everyone’s surprise, he graduated with an outstanding assessment on July 18, 1940.

Marseille joined the attack on Britain on August 24 and shot down his first British plane but at the cost of abandoning his wingman, for which he got in trouble. His fourth victory occurred on September 18 for which he again got in trouble. He had ditched his leader, who was killed.

There was a war on, and Germany needed every able-bodied man it had. So Marseille achieved three more victories before they kicked him out and reassigned him to the 52nd Fighter Wing (JG 52). Nothing, however, changed.

Then they transferred him to JG 27 on December 24 under Group Commander Eduard Neumann. Neumann knew that Marseille was a troublemaker but saw his potential. Which was why he transferred the new kid to North Africa – where he would earn the title, “Star of Africa.”

Marseille was a party animal who was often too hung over to fly. Based at an airfield just outside Tripoli, Libya, the lack of available women would eventually change all that. It was in North Africa that he learned to hone his skills, mastering a form of aerial combat known as deflection shooting.

This involves shooting not at the enemy per se, but at where they will be, based on their trajectory. He took it a step further, however, by coming at them from a high angle instead of the standard fly-in-from-behind-them-and-shoot.

He not only took risks that went against the rulebooks but also learned to get in close to his enemies. As a result, he used far fewer bullets than most – averaging about 15 per hit. By February 1942, he had 50 victories. By the end of June, he had scored 101.

He was sent back to Germany in June to meet Hitler. During a party hosted by Willy Messerschmitt (designer of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighter plane), he was asked to play the piano. He did so, starting with some classics before moving on to play American jazz – which was banned as Hitler considered it “degenerate.” Upset, Hitler left.

The following month, Marseille was at another party when he heard officials talking about the Jews. That visibly upset him as his family had been friends with a Jewish doctor who had delivered him at birth. The official line was that the Jews had simply been sent off to Eastern Europe.

Marseille now knew otherwise. On August 13, he was in Italy to receive an award from Benito Mussolini, after which he disappeared. The Gestapo found him, eventually, and convinced him to return to his base. He had a fiancée, at the time, and some historians suggest she was the leverage they used on him.

It must have worked; on September 1 he downed 17 planes in three sorties – bringing his total to a whopping 126. It should be noted, however, that the British deny this, claiming he shot down less.

Whatever the case, September 1942 was his most productive month with 54 kills. Eight of these were shot down in 10 minutes – the most brought down by a lone pilot in a single day. This earned him a type 82 Volkswagen Kübelwagen as a gift, as well as the rank of Hauptmann (Captain) – becoming the youngest to hold that position.

While he enjoyed the promotions, awards, and praise, the killing bothered him. To atone, he would sometimes fly over a downed plane to see if its pilot survived. He would then write a letter, fly over Allied positions, and drop it to them. Included were coordinates so they would be able to retrieve their man – something he called “penance” and done completely against orders.

As the war continued, the Axis powers became outnumbered, and Germany was running out of skilled pilots. Unlike the Allies who could rotate their men and give them a much-needed break, Germany could not.

By September 26, Marseille made his 158th claim, but it came at a price – he was so exhausted he could barely get out of his plane. His superiors wanted to send him back to Germany for a vacation and to attend a speech Hitler was giving.

Marseille refused, claiming his men needed him.

On September 30, his cockpit began filling up with smoke. Unable to return to base, he bailed out and was hit by his plane’s vertical stabilizer.

To the horror of his watching comrades, he hit the ground some 4.3 miles south of Sidi Abdel Rahman – without deploying his parachute. His death so traumatized his unit they were put on furlough for almost a month.

Marseille, who downed 158 planes (albeit in contention) with his Messerschmitt Bf 109, became its 159th victim.