A prisoner once quipped Hanns Scharff “could get a confession of infidelity from a Nun.”

His wife’s freshly baked pastries and cookies, and pleasant strolls in the picturesque German countryside, are not what anyone would associate with Nazi interrogation techniques during the Second World War.

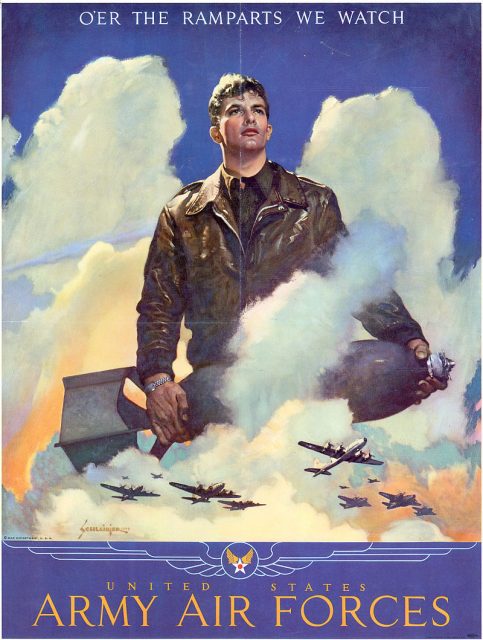

When we think of the captured Allied servicemen’s wartime questioning, we might imagine dank and dingy cellars and walls lined with horrible torture devices. The mind’s eye might even conceive a limping Gestapo officer in a leather overcoat plying his gruesome trade with malicious gusto.

It was not so for Hanns Scharff.

He used kindness and subterfuge to interrogate his charges. The “master interrogator” for the German Luftwaffe, as he was often called, created a bond with captured Allied pilots. His stratagem was subtle and calculated, and he never resorted to hurting any of the people with whom he came into contact.

Today, he is considered the father of modern interrogation practices.

He was an unlikely candidate for his role.

Scharff, who was born on December 16, 1907 in Rastenburg, East Prussia (today’s Kętrzyn, Poland) was always more of an artistic type – a fact that would very much come to light in his later life.

His father, Hans Hermann Scharff, was a hero of the First World War and his mother, Else, was the daughter of the founder of one of Germany’s largest textile mills.

Despite his older brother being the heir to his grandfather’s textile mill, Hanns Scharff also joined the family company. He learned quickly and was soon promoted as the head of the Overseas Division.

Scharff chose Johannesburg, South Africa as his base of operations, where he lived for ten years leading up to the war. It was where he met his British wife, Margret Stokes. She was the daughter of pilot Captain Claud Stokes, who served first in Rhodesia and later for the Royal Flying Corps.

When the Second World War broke out, Scharff was vacationing in Germany with his wife and three children and was unable to return to Africa due to travel bans.

Scharff’s wife saved him from the horrors of the Eastern Front.

Stranded in Germany, Scharff found work in Berlin. However, it did not take long for the war to escalate, and like so many of his fellow countrymen he was drafted into the Wehrmacht. Within months of his basic training, he received the order for his imminent departure to the Soviet Union.

Margret Scharff, his wife, would not hear of what seemed to her mind a ridiculous order. Without hesitating, she talked her way into an introduction with her husband’s commanding general. She convinced him that her husband’s talents, especially his fluency in English, would be wasted in the Soviet Union.

The general, won over, telegrammed Scharff’s direct superior and informed him that Scharff had been gazetted into the Dolmetscher Kompanie XII (Interpreters Company 12), based in Wiesbaden. It was not a moment too soon for Scharff, because he was just about to leave for the Eastern Front the morning the telegram arrived.

But Scharff was dissatisfied with producing “little round holes” – the words he used to describe his role as a clerk.

So once again, the general became convinced that Scharff’s talents would be better suited elsewhere. He ordered Scharff’s transfer to the Luftwaffe interrogation center at Oberursel, north of Frankfurt. His new posting was officially known as Auswertestelle West (Intelligence and Evaluation Center West).

It was there that Scharff first came into contact with the initial in-processing and interrogation methods for all captured Allied air force personnel, except for Soviet aircrews who were interrogated elsewhere.

Scharff quickly learned the ropes even though he never received proper interrogation training, learning only through observation. When his superiors became casualties in an airplane accident, he was promoted to head interrogator of the US Army Air Forces Fighter Section.

The Scharff interrogation technique was born.

Scharff’s method consisted of four key components:

- A friendly approach

- Never press for information

- Create the illusion of knowing everything

- The confirmation/disconfirmation tactic

In the confirmation/disconfirmation tactic, the interrogator presents a claim with the aim of making the prisoner react by confirming or disconfirming it. This approach was completely different from the usual direct method in which the captive was asked a series of prepared questions. Scharff, by contrast, made claims to elicit emotional responses.

More importantly, the master interrogator created an air of intimacy with the subject, and always professed to know far more than he did. He demonstrated his knowledge by telling the captured pilots everything he already knew about them, consequently making them falsely believe that whatever they told him was already common knowledge.

Scharff also liked to use the Gestapo’s vile mystique as a tool. He frequently cajoled his charges with the aforementioned country strolls and pleasant environment and then claimed that, regretfully, things would change if he were forced to hand them over to the secret police. He even offered them home baked cakes made by his wife! This tactic invariably worked because the infamous Gestapo was a household name for almost all of the prisoners.

Scharff was not always successful.

When the top American fighter ace, Francis “Gabby” Gabreski, was shot down, Scharff casually greeted the pilot he admired by stating that he had been expecting him for some time. However, the American never divulged any information.

Even so, the two men remained friends well after the war, and in 1983 they even reenacted the interrogation at a reunion in Chicago.

Read another story from us: The Female Spy who was Feared by the Gestapo in WWII

After the war, Hanns Scharff and his family immigrated with his family to the USA.

Finally, he was able to pursue his real passion for art. He started a company called Hanns Scharff Designs, which focused on mosaic designs and was an almost immediate success. Some of his more famous work includes the mosaic floor at the California State Capitol and the mosaic entry ramps at Disney’s Epcot Center in Florida.

The company he founded, which was later renamed Scharff and Scharff when his daughter-in-law joined him, exists to this day. Monika Scharff still runs the company, 26 years after Hanns Scharff passed away on September 10, 1992.