During World War II, a large number of prisoners underwent medical experiments in German concentration camps.

In Auschwitz and other camps, prisoners were subjected to experiments with the goal of developing new weapons and methods of treating German soldiers.

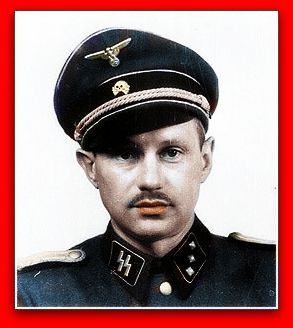

However, among the Nazi doctors was one man, Hans Wilhelm Münch, who received the nickname “The Good Man of Auschwitz.” He was called that because he developed many elaborate ruses to save prisoners’ lives and refused to help in murders.

Hans Münch was born on May 14, 1911 in the city of the German Empire called Freiburg im Breisgau. After graduating from high school, he began studying medicine at the Munich and Tübingen universities, where he joined the political section of Reichsstudentenführer.

In 1934, Hans joined the National Socialist Mechanized Corps and the National Socialist Union of Students in Germany and in May 1937 joined the Nazi Party. In 1939 he received his doctorate, then got married and began working in Bavaria.

After the start of WWII, Hans decided to serve in the Wehrmacht, but he was refused because his work as a doctor in the rear was considered too important. He replaced the doctors who were drafted into the army.

In June 1943, Hans was recruited as a scientist and was sent to the Hygiene Institute of the Waffen-SS in Raisko. This institute was located about 2.5 miles from the Auschwitz concentration camp. There, Hans was engaged in inspections of prisoners and bacteriological research. Josef Mengele, who came from Bavaria and was known as the “Angel of Death,” worked with him.

In his book about SS physicians of Auschwitz, Robert Jay Lifton mentions Hans Münch as a doctor whose commitment to the Hippocratic Oath was stronger than his loyalty to the SS.

Unlike other doctors, Münch refused to take part in the “selection” process. This determined which Jewish men, women and children would work, be experimented on, or die in gas chambers upon their entrance to the camp. Münch considered this process disgusting and inhuman. His refusal to participate in it was confirmed by the testimony of witnesses at his trial.

Despite his rejection of the selection, Münch did conduct experiments on prisoners. However, he used various tricks in order to stretch the timeframe of the experiment for a long time, while causing a minimum of harm to the prisoner’s health. Thus he saved the lives of many people, since when prisoners became useless for the experiments, they were sent to the gas chambers.

In 1945, after evacuating from Auschwitz, Münch spent about three months in the Dachau concentration camp. After the end of the war, he was unable to hide the fact that he had worked as a doctor in Auschwitz, and therefore was arrested in an American internment camp.

In 1946 Münch, as a captive, was taken to court in the Polish city of Krakow. During the first Auschwitz trial, a number of charges were brought against him, but many former prisoners came out in support of Münch.

On December 22, 1947, he was acquitted by a court decision “not only because he did not commit any crime of harm against the camp prisoners, but because he had a benevolent attitude toward them and helped them, while he had to carry the responsibility. He did this independently from the nationality, race-and-religious origin and political conviction of the prisoners.”

The decision of the court was based in particular on Münch’s refusal to participate in the distribution of prisoners. Of the 41 Nazis in the trial, only Hans Münch was acquitted. After that, people began to call him the “Good Man of Auschwitz,” for saving many people from death in the gas chambers.

After the trial, Münch returned to Germany and began working as a practicing doctor in Rosshaupten, Bavaria. In 1964, as an expert, he was invited to the second Auschwitz Trial, which took place in Frankfurt am Main. In West Germany, Münch took part in ceremonies and discussion meetings. In 1995, at the invitation of Eva Mozes Kor who survived the experiments of Josef Mengele, he again visited a concentration camp.

In old age Münch suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. At this time, he made several public statements in support of the ideology of Nazism. He was tried to be held accountable for such statements, but no court passed a final verdict given the fact that he was not in his right mind. Despite this, he was nevertheless convicted in absentia in France for inciting racial hatred against the gypsies.

Read another story from us: 4 Incredible People Who Helped Smuggle POWs Out of Nazi Europe

In 2000, due to progressive dementia, the prosecution of Münch was discontinued. A year later, at the age of 90, he died in Allgäu near Forggen Lake.

In 1997, Münch appeared in the documentary In the Shadow of the Reich: Nazi Medicine, and in 1998 he appeared in the documentary The Last Days. The footage of their chronicles with him were used in the 2006 film called Forgiving Dr. Mengele.