It has been said that some men who achieve greatness are not necessarily great men. That can refer to moral turpitude; it can refer to a lack of charity toward one’s fellow man.

Whatever the reason, there may be no field of endeavor in which that saying is more illustrated than the Armed Forces, particularly when men are desperately needed to fill the ranks as they diminish during wartime through soldiers killed in action.

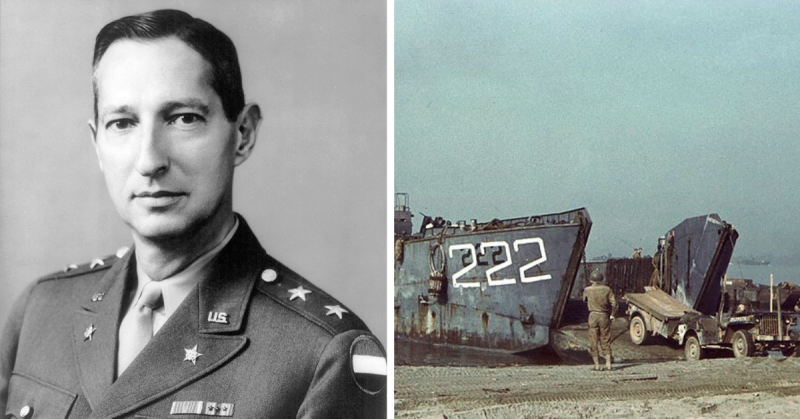

A prime example that emerged from World War II is General Mark Clark–a controversial man at best, an inept and uncaring man at worst. He served in both world wars and was a favored son among the high ranks of Army personnel, but he was despised by many, including some officers, who served under him.

Clark rose through the ranks quickly after receiving his military training at West Point Academy. Going to the Academy virtually guaranteed that graduates would be officers if they saw combat, and Clark became a Second Lieutenant thanks to World War I.

He then became First Lieutenant, and then Captain in 1917, a heady pace for even the most skilled military tactician. But during peacetime, his career came to a sudden stop, and it was not until 1933 that he was promoted to Captain. He eventually made Major, and in 1941 he got his first General’s star–the same year America entered World War II.

Some thought Clark better at strategically creating positions for himself at command headquarters than planning strategies for actual battles. Either way, whether due to political maneuvering or military acumen, Clark made Lieutenant General in 1942. In spite of what many men who served under him perceived to be ineptitude, he was given command of the newly-minted 5th Army in Europe, where he was expected to plan the invasion of Italy.

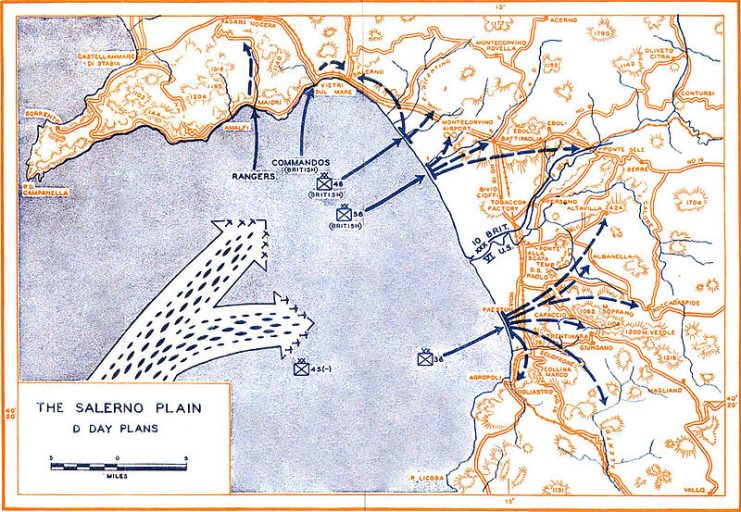

Clark loved to make it known that he was fearless when facing off with the enemy, and to the chagrin of some, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for the Battle at Salerno. But perhaps as a harbinger of bad times to come, the British held Clark accountable for the high number of deaths and injuries at Salerno.

Despite this, Clark became Commanding General of II Corps, and he devised the disastrous crossing of the Rapido River in January 1944.

The Battle of Rapido River was intended to be an assault on German forces that would allow the Allies to seize control of Italy, or at least part of it. Unfortunately, despite warnings from his peers and Mother Nature, Clark insisted on attacking the Germans in a full, head on assault.

Due to heavy rains, the river was swollen and even more difficult than usual to cross. Clark was adamant that the troops move forward regardless, and it cost 1,600 men their lives, with another 700 captured. By contrast, military historians assess German losses at just 65 men.

The survivors of the battle felt almost betrayed by Clark. Back on American soil, they complained–first to one another, then to state officials, and finally all the way to Congress. Their concerns were heard by a Congressional Inquiry, but ultimately Clark was not reprimanded for his decisions in that bloody battle, even though the “Texas Infantry,” as the 36th Division was known, was almost wiped out. The battle is considered one of the worst failures of the Allied forces in World War II.

Read another story from us: Before Paris, There was Rome: the Forgotten Front

It is difficult to know how history will judge General Clark, because history is measured in centuries, not decades. It hasn’t been even one century since the Battle of Rapido River. But Clark’s actions still raise ire in the state of Texas, from where many in the 36th Division came. If those soldiers and their descendants have anything to say about it, his role in those fateful 48 hours will forever remain a tarnished one in both minds and textbooks.