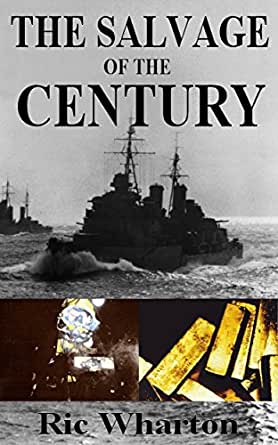

Toward the end of 1981, a team of divers working at incredible depths in the Barents Sea found and recovered a king’s ransom in gold bars from the wreck of the HMS Edinburgh that was scuttled on the 2nd May 1942.

On the 28th April 1942, the Edinburgh left Murmansk, commanding the escort attached to convoy QP11, containing 17 ships.

The Edinburgh was loaded with 4,570 kilograms of gold belonging to the Soviet Union. The gold was a payment to the United States for wartime materials and equipment supplied by the US.

In the bomb-room were 465 gold ingots stored in 93 wooden boxes. The bullion value was £45 million in 1942 with a value of £173 million ($222 million) today.

On the 30th April, a German U-boat, U-456, spotted the convoy after being alerted to its presence by German aerial reconnaissance planes.

The submarine fired a torpedo that hit the Edinburgh just forward of the bomb-room where the gold was stored. The Edinburgh crew immediately swung into action, closing the watertight bulkheads, so the ship did not sink quickly.

Soon after firing the first torpedo, a second was launched at the Edinburgh, hitting her in the stern where it wrecked her steering.

The Edinburgh was utterly disabled and taken under tow to be helped back to Murmansk. As she was wallowing along, she was constantly threatened by German torpedo bombers. Just off Bear Island, she was attacked by German destroyers.

She cast off the tow lines. Despite only being able to sail in circles, she brought her guns to bear on the attacking destroyers and managed to severely damage one of them.

Edinburgh was then struck by another torpedo on the opposite side of the ship from where the first torpedo struck, so she was now being held together by her keel and deck plates. At this point, her crew was instructed to abandon ship, and 840 men were taken off.

To save the gold falling into the hands of the Germans, the HMS Edinburgh was scuttled by HMS Harrier and HMS Foresight, taking the bodies of 60 crew to the bottom with her.

After the war, the British Government knew where she was, and salvage rights were offered to a British company. However, with the Cold War onset and the strained relations between the UK and the Soviet Union, salvage was put on hold. Also, the wreck was declared a war grave, which further complicated the recovery.

In the early 1980s, the British Government again resurrected efforts to salvage the gold. There were concerns that the wreck would be looted, and the war grave desecrated. The salvage rights were given to a consortium of Jessop Marine, Wharton Williams Ltd, a company specializing in underwater work, and OSA, a specialist shipping company.

They undertook to cut into the wreck to locate the bomb-room rather than using explosives to smash their way in. Cutting in was considered acceptable as the wreck was a war grave.

In April 1981, an OSA Survey Ship located the wreck approximately 400 kilometers north-north-east of the Kola Inlet at a depth of 800 feet. Using a remotely operated vehicle, they took detailed film of the debris to facilitate the drawing up of a salvage plan.

In August of the same year, the recovery team under the leadership of a former Royal Navy Clearance Diving Officer, Mike Stewart, started their recovery effort.

Two weeks later, John Rossier, a diver, found the first bar of gold. On the 7th October, poor weather conditions forced a stop to the recovery efforts. The team of divers had brought up 431 of the 456 missing ingots.

In 1986 a further 29 bars were recovered. This leaves five ingots still in the wreck, but it is not economically feasible to locate them.

This recovery still stands as a world record and was extremely dangerous. The divers worked in teams of two and spent days in surface pressure chambers to acclimatise their bodies to the rigours of working at depths of 800 feet with pressures of 35 pounds-per-square-inch.

They went down to the wreck in a diving bell, then one diver would leave and work on the recovery while the other remained in the bell.

The bell and divers were tied to the dive ship via umbilical cords that supplied communications, food, air, and electricity. They had to have warm water pumped through their suits to enable them to work in bitterly cold temperatures at the bottom of the Barents Sea.

Once inside, the divers worked in the pitch dark, in freezing conditions, and trying to locate the gold in a room packed with munitions that were unstable and needed to be carefully moved to collect the gold bars, each weighing 11kgs. The gold bars were loaded into a wire basket for transport to the surface.

The bombs that brought to the surface were defused on another vehicle by British ordnance specialists.

The US received none of the gold as they had been compensated by the insurance, so the gold was divided between the salvage consortium, the UK, and the Soviet Union. The salvage consortium received 45% of the recovered gold. The UK received one third and the Soviets two-thirds of the remainder.

Another Article From Us: Gravestone for Dambusters Dog Replaced Due to Racist Name

This represents a very lucrative payday for the consortium, even after payment of the taxes due to the British Government. At the time, the consortium was paid nearly $40 million for their work.