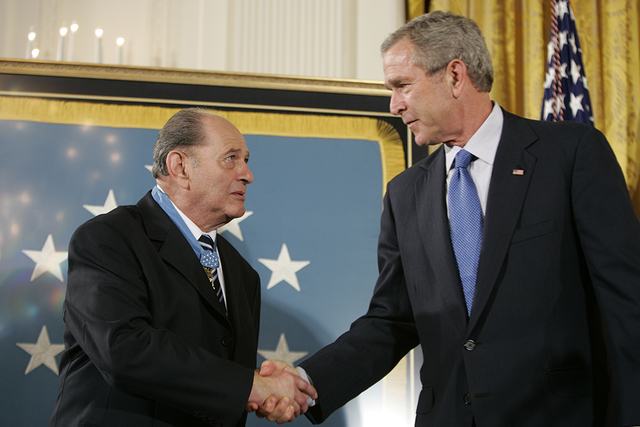

In 2005, President George W. Bush placed the Medal of Honor around the neck of a hero. That hero did not earn that medal during either of the Gulf Wars, or in Afghanistan. No, he had merited it fifty-five years before, during the Korean conflict.

Tibor Rubin, a Hungarian Jew known as “Ted,” went to the United States after World War II, joined the Army, and was sent to Korea. While there, he was given some of the most dangerous assignments his sergeant could think of. Why? Because his sergeant was an anti-Semite who hoped that by giving Rubin the most deadly assignments, he would get him killed.

That sergeant didn’t succeed. Neither did the North Koreans, the Chinese, or…the Nazis. Before he emigrated to the United States, Rubin had been rounded up by the SS and sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria, where he was held for fourteen months.

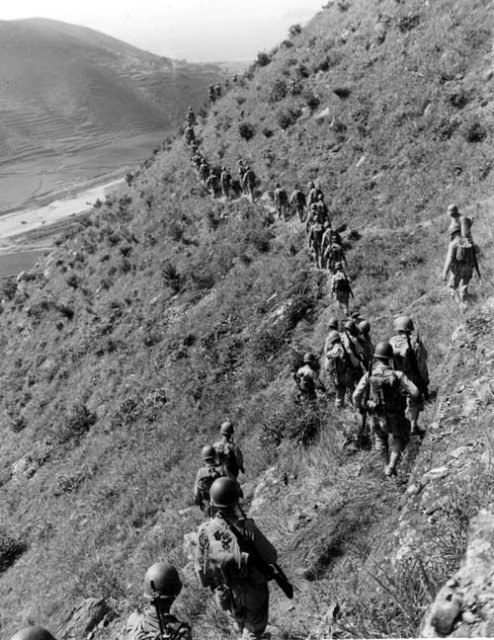

(U.S. Army photo)

Mauthausen was notorious for working its prisoners to death, particularly in its quarries, where brutal guards tormented and killed their captives. The most infamous part of Mauthausen was the “Stairs of Death.”

These were steps cut in the slope of the quarry, where prisoners were forced to carry large blocks of granite on their backs – over and over again, many dying in the process. Other times, guards would intentionally drop rocks on prisoners and take bets whether they hit.

One had to be tough and a little bit lucky to survive Mauthausen for fourteen months. When the war ended, Rubin and many of the other survivors in Mauthausen were at death’s door but were saved by US Army medics. One of the reasons he joined the US Army in 1950 was to show his appreciation for his liberation and the care he received afterward.

Sadly, Rubin’s father, mother, and younger sister all died at the Nazis’ hands. His older brother escaped to the West at the beginning of the war and fought with both the British and in the Czech underground resistance.

After arriving in the United States in 1948, Rubin worked as a shoemaker and then apprenticed as a butcher in New York City at a Hungarian-owned butcher shop. In 1949, he tried to enlist in the US Army, but his language skills kept him out. The next year, he tried again, and two fellow volunteers secretly helped him pass.

Rubin was one of the unlucky few stationed in Korea at the beginning of the Korean War. American troops, caught unaware by the North Korean attack, were driven down the length of the peninsula.

Rubin served in I Company, Eighth Cavalry Regiment, First Cavalry Division, covering the retreat of US forces. Many of the men in his company were country boys with little exposure to people from other parts of the world, and most of them treated Rubin well.

Sergeant Arthur Peyton did not. He constantly sent Rubin into the thick of things.

Rubin was a one-man wrecking crew. All alone on a hilltop, he held off waves of North Korean soldiers. Other actions were similar. Four times he was recommended for the Medal of Honor by two of his commanding officers.

Both of those officers were killed in action shortly thereafter, but they had previously ordered Peyton to begin the paperwork needed for the next step in the Medal of Honor process. Other soldiers from Rubin’s unit were present at the time, and heard the officers give Peyton the order.

The process to award Rubin the Medal never began, however. Later, a soldier that served with both Ted and Peyton testified: “I really believe, in my heart, that [the sergeant] would have jeopardized his own safety rather than assist in any way whatsoever in the awarding of the Medal of Honor to a person of Jewish descent.”

In the Chinese offensive in late 1950, which threw US and Allied troops back from the Chinese/North Korean border, Rubin was seriously wounded. He was captured by the Chinese after holding them off for hours behind a .30 caliber machine gun.

For the next two and a half years, he was a prisoner of war (POW). Despite a serious lack of medical care, Rubin recovered from his wounds. When he did, he found that many in the camp had lost all hope. There was little sense of comradeship and every man seemed to be out for himself.

Rubin was determined to change that. Almost every night, he would sneak out of camp – a tremendous risk, for if he was caught he would no doubt have been shot, and likely tortured first.

He stole food from North Korean and Chinese supply depots in and near the camp. He was never caught, and he always shared what he got evenly with the other men in his barracks. Not only did he keep the men alive with food, but he also carried the sick to the latrine, nursed those who fell sick, and much else.

Though there is always a middle ground, many Holocaust survivors fell into opposite camps: those who lost their belief in God, and those whose faith grew stronger. Rubin’s faith never wavered, and he looked on his deeds as the “mitzvahs,” or the shared blessings and good deeds of Jewish tradition.

Upon repatriation, the POW’s that came home with Rubin credited him with saving the lives of forty men. Even more astonishing was that during his captivity, Rubin had had a chance to be released – the Chinese offered to send him to Hungary, now a communist ally. Rubin had refused.

Read another story from us: 5 Interesting Facts About the Korean War

In 1993, the US Army set up a commission to study racial discrimination in the awarding of citations for bravery. In 2001, the case of another Jewish soldier, Leonard Kravitz, caused Congress to instruct the military to look further into other cases involving Jewish troops. One of them was Ted Rubin’s, and in 2005, the old wrong was righted.

In December 2015, Tibor “Ted” Rubin passed away. The local VA center in Long Beach, California, where he volunteered for years, was named in his honor.