The Hollywood movie, The Great Escape, earned worldwide fame for its cool actors and its loose connection to a real-life escape from a Nazi prisoner of war camp. But the World War I prison camp of Holzminden had its own share of bold and daring escapes.

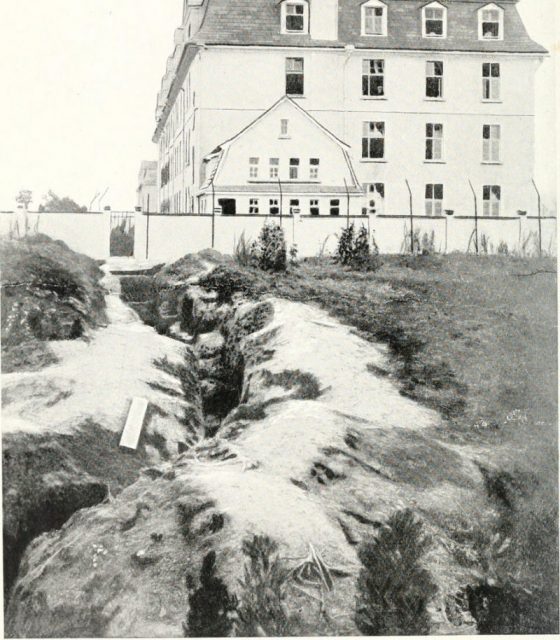

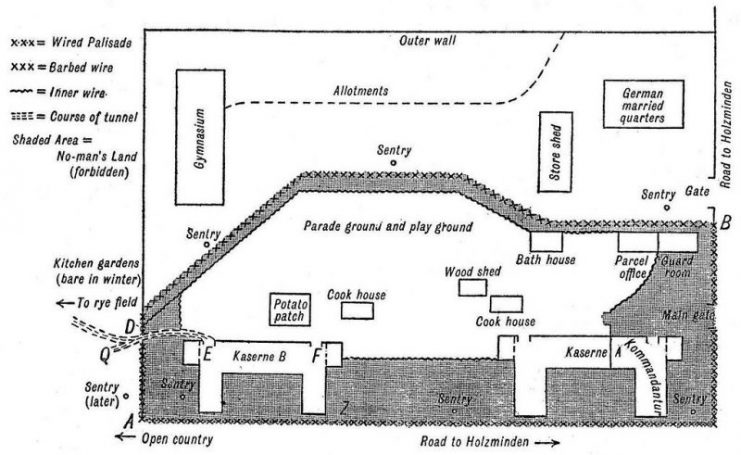

The Germans created Holzminden as a cavalry base in the German province of Saxony. Following overcrowding at other prison camps in late 1917, they converted it into a prisoner of war camp.

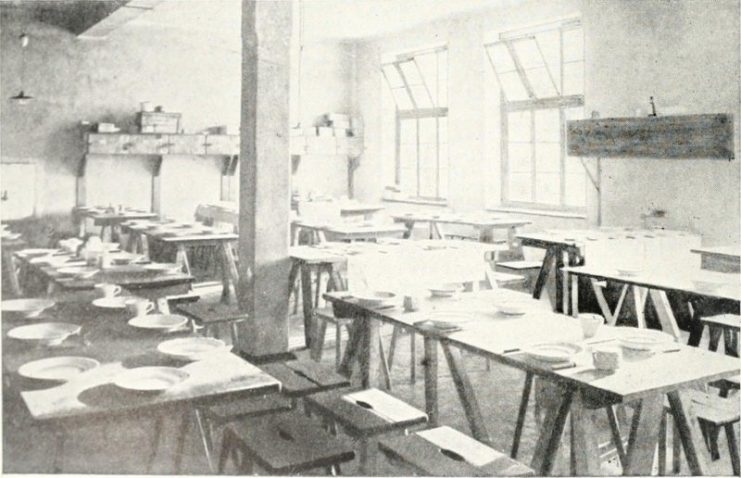

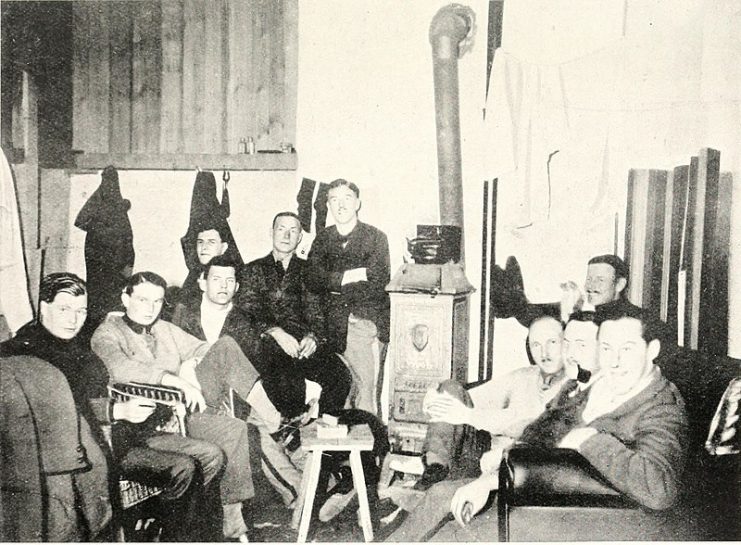

The prisoners lived in two four-story barrack blocks. Buildings A and B were partitioned, so that the officers lived in one half of buildings A and B while the other half was occupied by the German garrison and enlisted prisoners that served as orderlies.

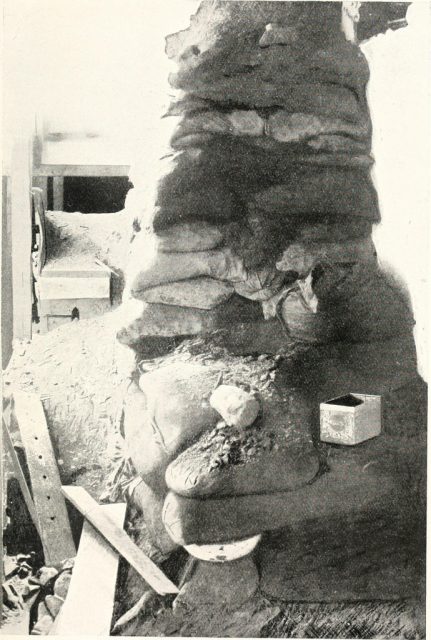

The rest of the camp included a wash house, cook room, and parade ground surrounded by barbed wire, no man’s land, and a barbed palisade.

Hauptmann Karl Niemeyer served as the Kommandment for most of the camp’s existence. He received a reputation for being capricious and often unfairly punitive.

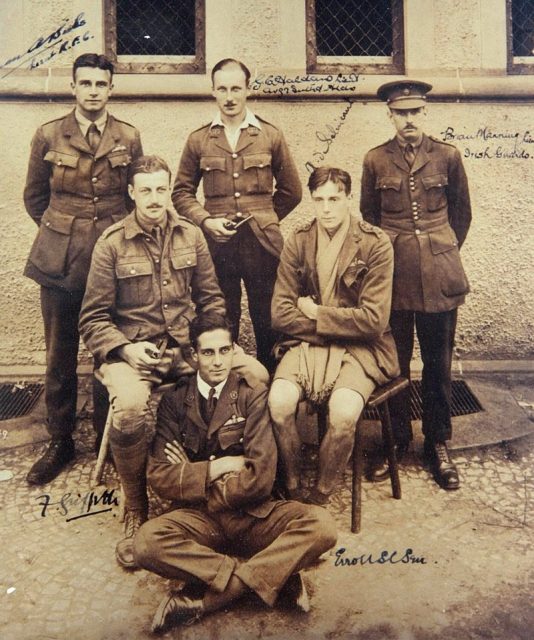

Among the prisoners were two “celebrities” who received particularly harsh treatment.

The first of those was William Leefe Robinson. Since he had once shot down a German airship over Britain, Niemeyer ensured that he spent plenty of time in solitary confinement during his stay at Holzminden.

Algernon Bird was the other prisoner to receive punitive treatment, simply for having the dubious honor of being the 61st person to be shot down by Baron von Richthofen, the Red Baron.

The prisoners weren’t fed very well, though the Germans can’t be completely blamed for that as the Allied blockade meant that soldiers and civilians in Germany weren’t eating that well either.

However, thanks to parcels from home and the Red Cross, in many cases the prisoners ate better than their German captors. The prisoners made sure to flaunt that fact when they could. Some Holzminden captives, for example, would draw their ration of bread from their German captors, throw it in the garbage, and then ostentatiously eat their care packages.

Escapes happened quite frequently. Most of them were simple, ad hoc affairs based on daring more than planning.

The escapees would use kitchen and improvised utensils to cut through the gate and make a run for it. They would dress as guards or civilian workers to fool the Germans. In at least one case, a prisoner dressed up a woman to pass through the gate.

These escapes worked well at first but had little long-term success. The gate guards didn’t fall for the ruse a second time, and most of the individuals were recaptured within days.

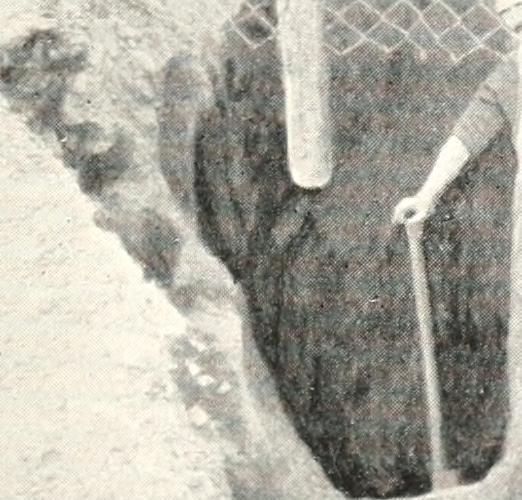

The great escape came with much more disciplined planning. The prisoners organized themselves and maintained secrecy for over nine months. Their primary task was digging a hole from under the staircase in the orderlies’ quarters to outside of the gates.

For the first few months, the officers had to dress up as enlisted orderlies to enable them to enter the quarters and help dig. But they created a secret door in the attic of Building B that let the officers move over to the enlisted side of the building.

They also used some of their care packages to bribe German officials and gain tools and other contraband that they needed.

On the night of the 23rd leading to the 24th of July in 1918, they were ready to go. Eighty-six officers planned to escape, but either the hole was too small or somebody had a few too many care packages because the thirtieth man became stuck in the tunnel.

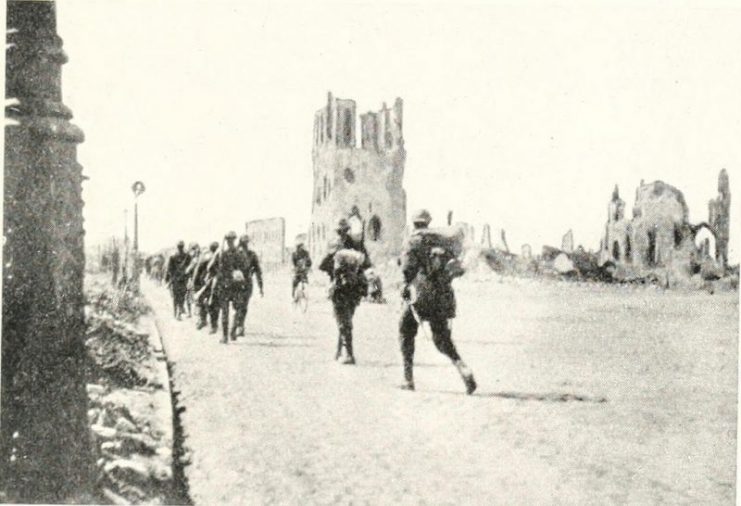

The twenty-nine that made it through the tunnel got a good head start until the morning. They didn’t do anything as cool like Steve McQueen jumping obstacles in his motorcycle, but the prisoners did use all of their resources to escape.

The senior British Officer, Col. Charles Rathborne, spoke excellent German. He changed into good civilian clothes, bought train tickets, and maybe even sipped some tea on the easy train ride to freedom.

The others had to make the journey on foot. Dodging enemy patrols and hiding in the woods, it took the ten individuals that completed the escape an average of 14 stressful, hungry days to walk (and run) to freedom.

This experience shows that any prison has its weak points, and a dedicated group of individuals with daring and discipline can find those weaknesses.

An escape works better with some kind of help from the outside, like transportation or food. Stockpiling food for the journey would also work. Knowing German and having money for the train were particularly helpful in this case.

Above all, fortune favors the bold. The Holzminden tunnel was a great escape that proved the strength of the human spirit and the unquenchable yearning for freedom.