Company volleys fired from these rifles created the loudest noise any living Zulu had ever heard in 1879. Their stopping power was brutal.

If you are a regular reader of my ramblings you may recall previous forays into the dramatic days of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879. This was a conflict orchestrated by British colonial leaders who were anxious to consolidate their power in southern Africa by drawing the whole region under the British umbrella.

The entire region was ripe for exploitation and secure frontiers and reliable administration were vital to future progress. The neighbouring Zulu nation had offered no significant threat to the colonists but although they represented a far more robust opposition, many Europeans assumed they would be no match for imperial troops.

Regular and colonial forces had been victorious over other indigenous peoples and it seemed obvious that the Zulus would be just as easy to deal with.

The British had enjoyed cordial relations with the Zulu king and he had no reason to quarrel with the English but Sir Henry Bartle Frere had other ideas and his aggressive policy would lead to disaster for both the British and the Zulu nation. He launched an avoidable conflict which would cost many lives and ruin reputations. For me, his actions stand out as one of the most cynical actions of Victorian colonialism.

However much misery ensued thanks to Bartle Frere’s folly, the conflict created legends of a number of British soldiers while creating a strong sense of respect and admiration for the Zulu army who defended their lands with extreme prejudice. I have no doubt there are many people outside of Great Britain who love a tail of redcoats getting a good hiding and, on the face of it, this certainly appeared to happen on 22nd January 1879 at the Battle of Isandlwana.

But this magnificent book by Colonel Mike Snook reveals just how bravely the British fought in the face of insurmountable odds. It was not the simple case of incompetence and failure painted in some histories and we learn just how professionally the imperial troops behaved as they held off the Zulu tide until overwhelmed.

The classic movie Zulu continues to focus attention on to the epic siege at Rorke’s Drift, where the Zulu reserve of the Undi Corps were held off by ‘B’ Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 24th Regiment of Foot just after the vanguard of the Zulu army had utterly destroyed the much of the 1st Battalion and elements of the 2nd at Isandlwana.

Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded for actions at Rorke’s Drift, there could easily have been more. The many British heroes of Isandlwana have not faired so well, in part because few of them lived to tell the tale.

The success of this book is in the way Colonel Snook scythes his way through the myths and falsehoods of the battle, several of which have become established due to the errors made in a book I will continue to love regardless of the convincing demolition of them by the author.

I well remember trotting down to my local bookshop in North London forty odd years ago where I snapped up a paperback edition of Donald R Morris’ The Washing of the Spears. That book tells the sprawling saga of southern Africa in the build up to the Zulu War and regardless of the glitches in the history telling Morris’ book remains a great read.

There is no question that Morris’ mistakes were made in good faith as he attempted to interpret the actions and conventions of a Victorian army that merited greater understanding. Colonel Snook sets out to tell the story of Isandlwana underpinned by a strong appreciation of how the British army worked over a century ago while his military background allows him to set actions in context.

What is a shame is how Morris’ interpretation has been swallowed by historians and enthusiasts alike and these were enforced by the forgettable movie Zulu Dawn. Snook shows how the British force maintained cohesion and firing discipline before isolated ‘squares’ were compelled to fight shoulder to shoulder to the bitter end.

The temptation to assume how those Victorian men felt by imposing 21st century mores on them is quite strong, but Mike Snook ignores all this nonsense. 19th century men die contemporary deaths in his book and it is no accident that he refers to the Little Bighorn as a comparable example of how indigenous forces could hand out brutal shocks to supposedly superior invaders.

There is a lot of detail in this book, some of it centring on the fearsome reputation of the Martini Henry rifle which fired a .577 Boxer cartridge. It was accurate up to around 400 yards (370 metres) and I can attest it was a brute to fire. I’ve shot with the rifle and been in the butts hearing the rounds coming in like an express train.

Company volleys fired from these rifles created the loudest noise any living Zulu had ever heard in 1879. Their stopping power was brutal, but all this firepower allied to the attendance of a couple of seven pounder guns and a battery rockets were no match for the thousands of warriors arrayed against them.

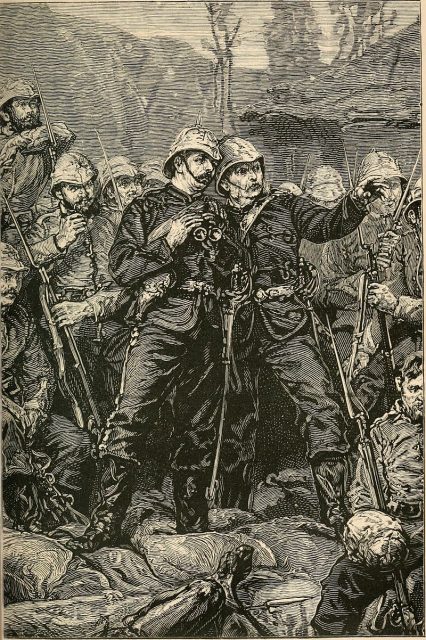

The camp at Isandlwana was badly prepared thanks in a large part to the arrogance and complacency of the British commander Lord Chelmsford who committed the cardinal sin of splitting his forces into columns, leaving the doomed defenders at their rambling camp while the remainder were extended to a dangerous degree.

Chelmsford had beaten other indigenous forces but he was reckless in his underestimation of Zulu martial prowess and his folly would see the ill-fated No3 column destroyed. Colonel Snook shows how Chelmsford had the bad habit of interfering in details junior officers would normally handle and it was his dominance and poor decision making that led to the disaster.

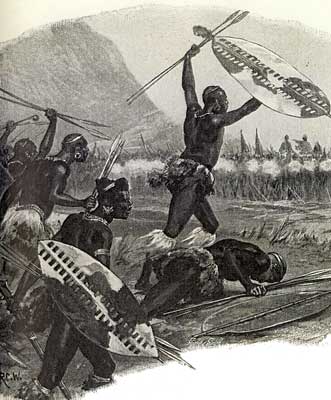

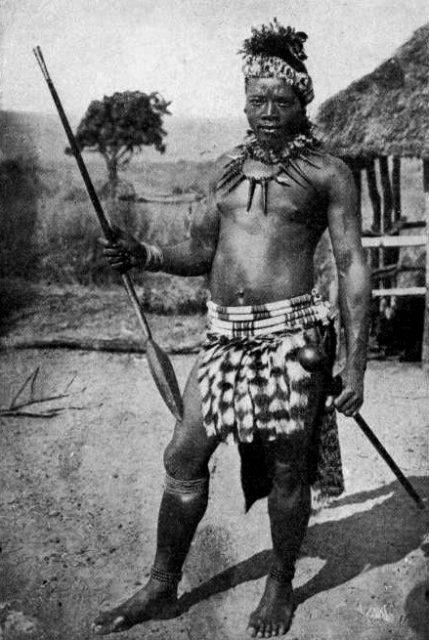

One aspect that colours many a history is the Zulu tradition of ritually disembowelling their enemies to release their spirits. It isn’t difficult to imagine how the battlefield must have looked with the bodies of over a thousand men treated in such a way. The Zulus were highly disciplined and well led.

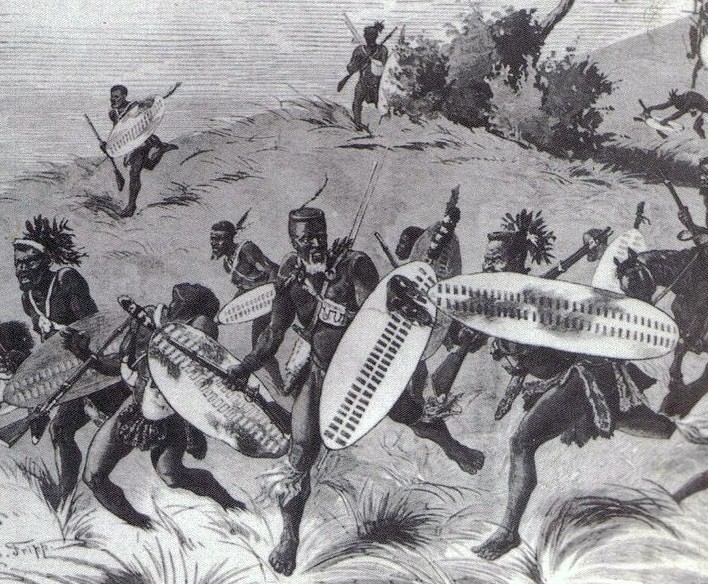

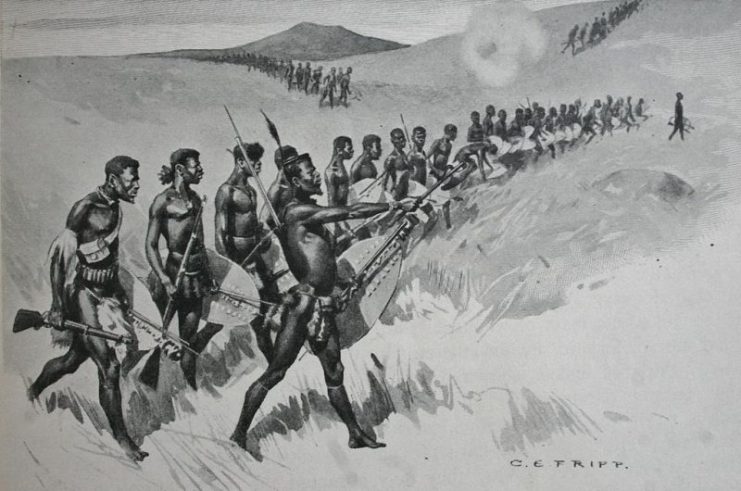

Their tactics were simple but incredibly effective, relying on speed of movement, weight of numbers and immense personal courage. The author shows that the notion the rifle armed Zulu were few in number and seriously ineffective is simply untrue. But this is not a distraction from the reality that a Zulu impi was a terrifying spectacle as it closed in. The warriors were fired up into a frenzy by their commanders – the induna – and their bloodlust was terrifying to most European eyes.

It is not difficult to imagine how impressive the 15,000 odd Zulu warriors appeared as they performed their famous buffalo horn tactic at Isandlwana. It is good to know their descendants continue to sing the songs made about some of the brave British soldiers who died fighting in the Zulu assault.

I love this book for a host of reasons. The detail is immense while the depiction of the battle is thrilling and terrible. Colonel Snook paints wonderful pen portraits of the leading figures and does much to bring them to life at the key moment when they looked death squarely in the face.

The folly of Chelmsford’s plan is laid bare while some of his staff officers come across as arrogant and disagreeable. The story has its share of die hards and mavericks and I was pleased to see how the author has done so much to rehabilitate a number of them because they fought and died well in the Victorian manner and deserve to be remembered as such.

If anything this book has restored much of the truth of Isandlwana that has long been overshadowed by Rorke’s Drift and somewhat hazy accounts of that terrible day in 1879 when the Zulus deservedly won their great victory.

The British limped away to lick their wounds after the battle, but the war wasn’t over. Suitably reinforced and better led, the second invasion was seen through with a greater sense of respect for the enemy culminating in the Battle of Ulundi when King Cetshwayo’s royal kraal was besieged and destroyed.

There is no happy ending. But Colonel Snook sticks to his battle, ending with the men who got to the British camp at Isandlwana far too late in the day and who had to spend a torrid night camped out amongst the eviscerated dead. The author’s power of description will knock your socks off and it is not difficult to see why such a great historian as Richard Holmes thought so highly of this marvellous book.

That it has been reissued is a really wonderful thing. I would say it is just as essential as Evan S Connell’s masterpiece about Custer. 19th century warfare can be a thrilling subject to get your head round and it is great to be able to cut through the caricatures of old soldiers who shake off cartoonish impressions to become flesh and blood. Mike Snook does all the men who fought at Isandlwana a great service.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

HOW CAN MAN DIE BETTER

The Secrets of Isandlwana Revealed

By Lieutenant Colonel Mike Snook

Frontline Books

ISBN: 978 1 84832 581 4