Alexander Jefferson of the United States Army Air Forces was flying a P-51 Mustang over Toulouse, France, in August 1944. It was by no means his first mission. Since being assigned to the 332nd “Red Tail” Fighter Group, he had flown nineteen such missions, charged with protecting the bombers, fighting off Luftwaffe aircraft, and attacking ground targets.

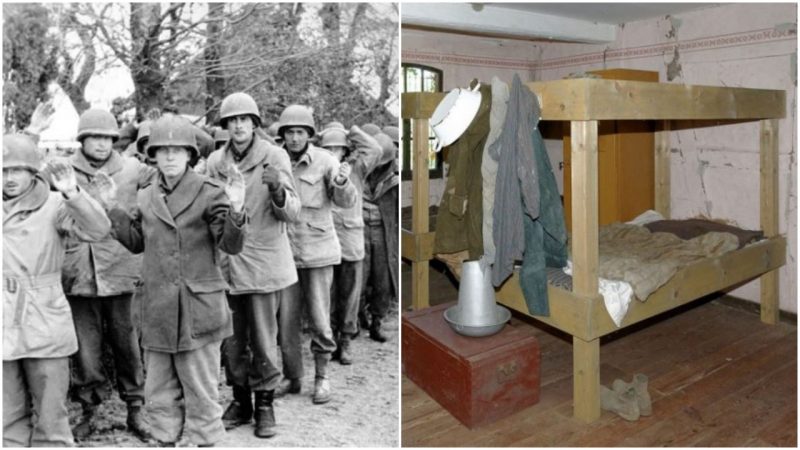

He had been fortunate thus far, but on this particular mission his luck was about to run out. His P-51 was shot down, and while he was able to eject and parachute safely to the ground, he was quickly taken prisoner. He was sent to a prisoner of war (POW) camp in Poland called Stalag Luft III – a camp specifically for captured Allied pilots.

Once at the camp, he was interrogated by the Germans. In the process, Jefferson was very surprised to find out that his captors not only knew exactly who he was, but they also had extensive information on his pre-war life, even down to private info such as his parents’ tax records and his high school transcript.

It must have seemed like the Germans acquired this information through a potent and extensive network of intelligence agents, with some surely having to be on the ground in the US – which was no doubt a worrying thought for the POWs imprisoned at the camp. The truth about how the Germans came to have all of this information, though, was far less sinister, although nonetheless impressive.

Gaining access to an enemy’s classified information, especially information about its technology and weapons, can swing the tide of a war. This was why the Germans had set up a POW camp especially for captured airmen – and it was to this camp that they sent some of their most crafty and ingenious intelligence agents.

The interrogation process would begin long before the prisoner was brought into an interrogation room. Indeed, it would start with his entry into the camp itself. POW camps have, throughout history, earned a notorious reputation for being hellish places with some of the worst conditions imaginable, and the German POW camps of WWII were no exception.

With regard to their specialty camps for captured airmen, the deplorable conditions did not simply exist because the Germans wished to be cruel to the prisoners – no, it was a vital step in setting the prisoners up to get their tongues to slip.

Usually, the captured prisoners in these “Luft” camps would be placed in solitary confinement from the moment they entered the camp. The conditions of this solitary confinement were brutal. Often they were kept in the dark for many days, with no natural light or, in some cases, not even any artificial light.

The cells would be freezing, and only survival rations would be given to the prisoners – and these rations were often so disgusting as to be barely edible. One prisoner described his first meal as having being “stale black bread and evil-tasting ersatz coffee made from oak leaves and coal.”

Sometimes, in addition to those deprivations, the guards would threaten the prisoners, suggesting that if they did not give up the information the Germans wanted, they would not treat their wounds, or would hand them over to the Gestapo as spies – which was a certain death sentence.

However, in addition to this torture, the Germans would apply a “good cop” routine. Indeed, the “good cop” routine was generally preferred, as it yielded results far more quickly.

A friendly interrogator would offer the prisoner time outside, a few cigarettes, and decent food and drink. Then the interrogator would chat casually with the prisoner – all of the interrogators were fluent in English – subtly directing the flow of conversation to the prisoner’s life back home, his interests and pastimes, his personal history, and such topics, avoiding direct questions about the prisoner’s military activities.

All information gained from such conversations, no matter how trivial or irrelevant it seemed, was recorded and stored in detailed files. This information could then be used with other airmen, to either get them to confirm something the Germans suspected, or as something with which to threaten them, making it seem, as in the case of Alexander Jefferson, as if they already knew everything anyway.

Seemingly irrelevant gossip proved to be especially valuable information for the Germans. When one particular major, a married man with children, was being stubborn and refusing to answer the Germans’ questions, they told him that unless he gave them the information he wanted, a broadcast would be sent out that he had been seen entering a hotel room in London with a beautiful blond woman the night before he was shot down.

The Germans knew the exact hotel room too – this was casual gossip another officer had let slip. The major was so shocked he apparently fainted.

German intelligence agents were also able to glean information from prisoners’ ration cards. They studied the type of pencil markings used on the cards to determine where they had come from. In addition, they were able to discover details about specific men from American newspapers.

In Jefferson’s case, for example, he was the only African-American student at his school who had participated in college prep classes, so the Germans may well have obtained press clippings about him from a local paper.

Another way in which the Germans could obtain detailed information was by giving the prisoners fake Red Cross forms, which they claimed would notify the prisoners’ families of their circumstances as POWs. The forms would request detailed information – and would often be spotted as fakes by the prisoners.

However, this was another psychological trick. In making it seem like the Germans were using desperate and lame tactics, they could manipulate the POWs into underestimating the interrogators’ abilities and thus let their guard down.

Presenting the POW with a glut of personal information about them, like they did with Jefferson, was an entirely different tactic. This strategy made it seem like the Germans already knew everything anyway, to get a POW to think it was futile to avoid answering their questions.

As the war progressed and more POWs were captured, the Germans were able to compile and cross-reference an increasingly broad and extensive amount of information. While such information would have been patchy in 1939, by the time Jefferson was captured in 1944, the Germans would already have compiled a great amount of intelligence with which to question prisoners.

In spite of all the information the Germans managed to wangle out of the many prisoners they captured, none of it ever proved to be a game changer. For all their efforts they eventually lost the war, surrendering on May 7, 1945.