White officers leading non-white men made particularly tempting targets for snipers, as the British Indian Army would discover in the First World War.

In 1866—only 33 years after slavery ended on the island of Tortola—Private Samuel Hodge, a pioneer in the 4th West India Regiment of the British Army, became the first black soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry available to the fighting men of the British Empire.

Samuel Hodge was born sometime around 1840 on the island of Tortola. It is now one of the British Virgin Islands, but at the time it was administered as the larger British Leeward Islands. Like most of the British possessions in the Carribean, Tortola was dominated by sugar cane plantations, which until 1833 were worked by slave labor.

Africans captured or kidnapped by rival chieftains were sold to British traders on the coast of west Africa and although the slave trade itself was banned by the British Empire in 1807 following a stuttering series of slave revolts and reforms, slave labor endured.

Slaves continued to be purchased illegally in Tortola, children born to slaves became slaves legally, and freed slaves were dumped on the island under mandatory 14-year “apprenticeships”—which was better than slavery, but it wasn’t exactly freedom—to keep the plantations’ profits flowing.

In the early 19th century, many slaves in the British Caribbean were sold already baptized with Christian first names and given the surnames of their masters. This is speculation, but it’s worth noting a particularly notorious plantation owner, Arthur William Hodge. With a reputation even among slave owners for cruelty, Hodge was finally hanged in 1811 for flogging a slave to death.

At the time of his conviction, he owned 100 slaves. It’s a total flight of fancy, but Samuel Hodge’s parents might have been among their number.

Despite attempts to ease the financial burden on the slave owners by forcing freed slaves to work a set number of unpaid hours and issuing compensation for each slave they lost, following emancipation in 1833 the economy of Tortola spiraled downwards.

We don’t know the story of Samuel Hodge’s early life, but what we do know is he was most likely born free but grew up at a time where there were few opportunities. Over the first 13 years of his life he witnessed two insurrections by the disillusioned black population, a cholera outbreak, devastating hurricanes, a long period of drought, and the collapse of the market for cane sugar.

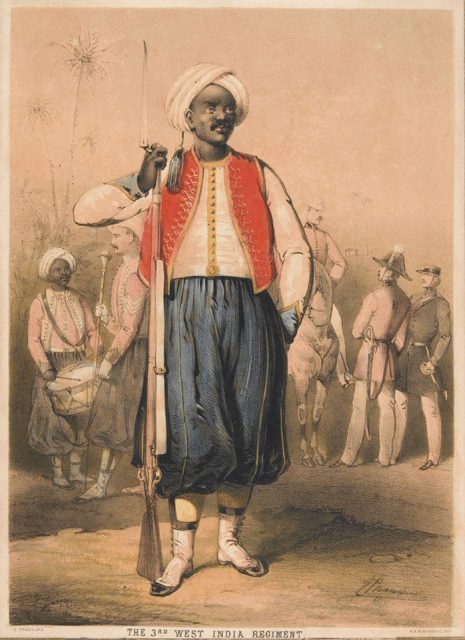

The allure of service in the bold crimson tunics of the West India Regiments is easy to understand. Raised in 1795 to protect Britain’s Caribbean colonies from their French rivals (and to invade those French colonies, of course), the West India Regiments originally consisted of escaped slaves who fought for the British in the American War of Independence.

When this first generation of free soldiers moved on, the numbers were replaced by slaves purchased specifically for military service. Between 1795 and 1807 as many as 13,400 slaves were purchased for the West India Regiments.

In 1807 these men had to be released under the Mutiny Act, as the idea of enslaved men bearing arms while the call for emancipation was growing streadily louder was asking for trouble. But replacing the West India Regiments with white troops simply wasn’t an option at the time.

One reason was that tropical diseases such as malaria resulted in fearsome fatality rates in Europeans. Also, the West India Regiment wasn’t only needed to garrison Britain’s Caribbean possessions, but were also increasingly required for service in British West Africa, a scattered network of former slaving and trading ports that included parts of what is now Sierra Leone, Gambia, Nigeria, and Ghana.

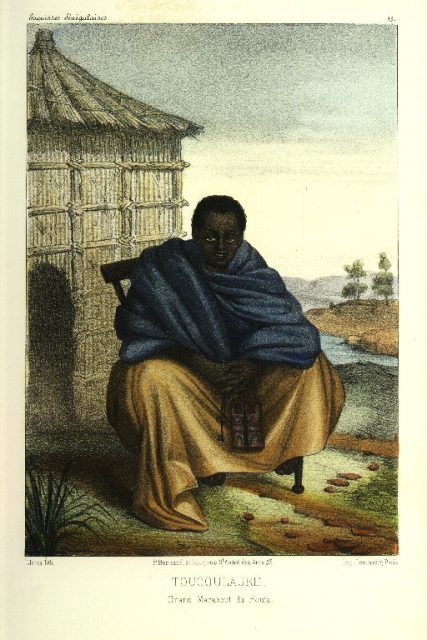

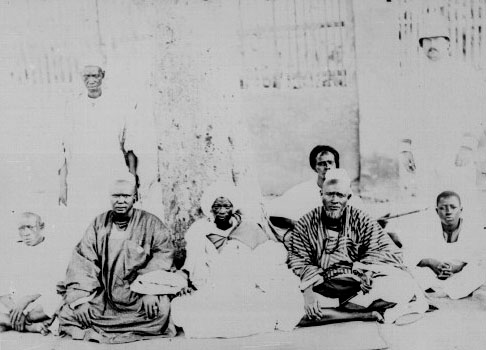

It was on the banks of the River Gambia that the 26-year old Private Samuel Hodge found himself answering the call of glory. The 4th West India Regiment was garrisoned at the town of Bathurst (now Banjul) on the British-held north bank of the Gambia. This thin British presence along the river and coastline was being increasingly challenged by the Marabouts, radical Muslims from the interior of the country.

The Marabouts had been waging a long insurgency, the Soninke-Marabout Wars, against the African Kingdom of Kombo and its rulers, who followed the indigenous faith.

British and French intervention had ended with them being granted more and more territory. This, in turn, brought Europe’s colonial powers into more direct conflict with the Marabouts and their local brand of Jihad, or holy war.

In 1866 Amar Faal, one of the few Marabout leaders who hadn’t been successfully cowed by Britain and France, began harassing tribes who relied upon the British for protection. It was imperative that the colonial authorities project the power that would keep the rest of the Marabouts in line and reassure Britain’s African allies that they had backed the right player.

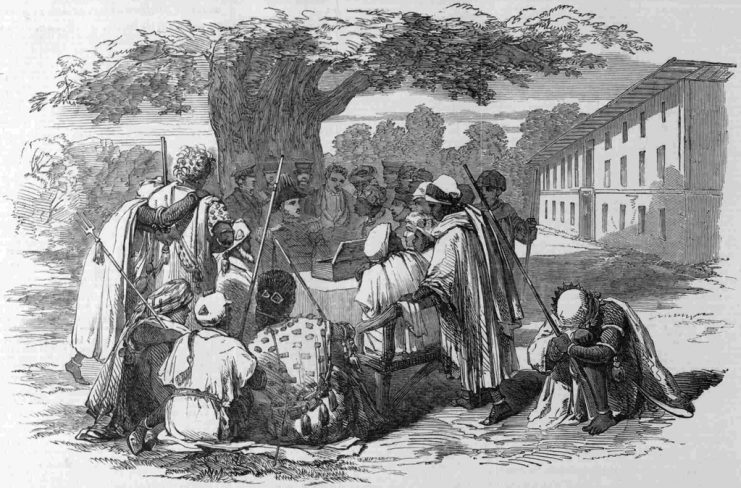

The British governor, Lieutenant Colonel George Abbas Koolie D’Arcy, took 370 men of the 4th West India Regiment and set off upriver on two boats towards Faal’s fortified town at Tubabecolong. En route, they were joined by roughly 500 warriors from the Soninke tribe. On July 30 they attacked the town.

Armed only with light firearms and rockets—more as psychological weapons than genuine artillery—the British force found themselves unable to crack open Faal’s stockade. D’Arcy had no choice but to call on the pioneers for a desperate suicide mission. Hodge was one of the men who stepped forward, took up an ax, and raced towards the enemy to cut their way in by hand.

The fifteen West Indians, two officers (Lieutenant Jenkins and Ensign Kelly) and D’Arcy himself immediately came under withering fire from the defenders. Jenkins and Kelly were killed almost instantly—white officers leading non-white men made particularly tempting targets for snipers, as the British Indian Army would discover in the First World War.

Eventually, all but three men made it to the base of the stockade: Private Hodge, Private Boswell, and, amazingly, Colonel D’Arcy. As the defenders continued to fire on them, most likely with antiquated ball muskets bought from Dutch traders decades earlier, Boswell and Hodge hacked a hole in the fence large enough to allow a body to squeeze through, before Boswell was cut down.

D’Arcy slipped through the gap first, followed by Hodge who cut through the fascinings on the gate before he was wounded. With only D’Arcy still standing, the gates swung open and the waiting 4th West India Regiment rushed in to put the town to the flame.

With the defenses fallen, the superior firepower of the British reaped a bloody toll on the Marabouts: hundreds were slain, while only two British officers and four men were killed, and around 60 wounded—Private Samuel Hodge among them.

Read another story from us: Beyond Brave: The First Ever Recipient Of The Victoria Cross

D’Arcy recommended Hodge for the Victoria Cross, and it was confirmed on January 4, 1867 with an announcement in the London Gazette that described: “Private Hodge was presented by Colonel D’Arcy to his comrades, as the bravest soldier in their regiment, a fact which they acknowledged with loud acclamations.”

Hodge returned to the Carribean and was presented with his VC on June 24, 1867 and was promoted to lance corporal. Unfortunately, he never recovered from his wounds and died on January 14, 1868.