The German battleship, Bismarck, was one of the biggest vessels ever built in the first half of the 20th century. A marvel of advanced engineering and technology, it was the most powerful ship in the world – yet a single shot by an antiquated biplane took it down.

At 792’8” in length, and with a beam of 118’1”, it displaced 49,500 tons of water. It was also deadly with eight 15” SK C/34 guns in four twin turrets, twelve 5.9” L/55 guns, sixteen 4.1” L/65 guns, sixteen 1.5” L/83 guns, and twelve 0.79” anti-aircraft guns, as well as four Arado Ar 196 reconnaissance floatplanes.

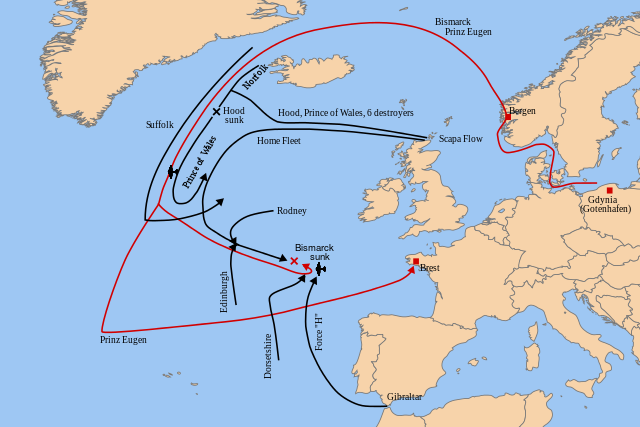

Its function was to destroy Allied convoys in the Atlantic, the lifeblood of Britain. On the 18th of May 1941, it set off under Admiral Günther Lütjens and Commander Ernst Lindemann, accompanied by the light cruiser, Prinz Eugen. Three days later, they were spotted near Bergen, Norway.

The British sent out the HMS Hood. Launched in 1918, it measured 860’7” in length and 104’2” at the beam. It had been upgraded in 1939, but not enough. More had to be done, but the war’s outbreak forced the Hood to patrol Iceland and the Faroe Islands to keep the Germans at bay.

When first commissioned, it was the biggest and fastest warship in the world, securing Britain’s grip over her colonies. The Hood, therefore, represented the height of British technology, naval power, and imperial might – making it a beloved icon.

With it went the HMS Prince of Wales (PoW), which was more up-to-date. Unfortunately, the technology was so cutting-edge that much of it was untested. It had ten 14” guns, but eight were housed in malfunctioning turrets. The Royal Navy knew this, but the Bismarck’s sighting had forced their hand.

The Hood and the Bismarck were almost evenly matched. Both had eight 15” guns that could shoot 1,700-pound shells over 15 miles. But the Hood could only fire two shells a minute compared to the Bismarck’s three. The latter was also more heavily armored, while the Hood was less so because it was designed for speed.

The British tried to reach the Denmark Strait before the Germans so they could “cross the T” before them. This strategy requires positioning the length of one’s ship to the front of an enemy ship, since ships have more guns at their sides than they do at the front. The one who crosses the T can then fire more salvos than the one who gets crossed.

But the Hood and the PoW got there too late before dawn on May 24, so it was the Germans who crossed the British T off the western coast of Iceland. The Hood was sunk at a little past 6 AM and the PoW had to retreat after suffering extensive damage.

Before it did, however, it managed three solid hits – puncturing the Bismarck’s fuel tanks and flooding its front lower decks with seawater. So the Bismarck headed toward Nazi-occupied France for repairs and since the Prinz Eugen could do nothing more, it headed off toward the Atlantic. Despite the damage, the Bismarck was still heavily armed and the captain felt confident about reaching France by dawn on May 27th.

Twenty-one British destroyers, thirteen cruisers, six battleships, and two aircraft carriers gave chase… but the German ship had vanished.

On May 26 at 10:30 AM, the Bismarck was found a mere 700 miles off the French coast. In another 500 miles, the sea and air would be filled with German ships and planes – so a British fleet closed in from the north, while another came in from the south.

At 7 PM, fifteen Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers took off from the HMS Ark Royal and split into three groups to attack. Lieutenant-Commander John “Jock” Moffat flew one of them. As he broke through the cloud cover, he was awed at the sight of the German behemoth.

The Swordfish plummeted at 115 miles per hour. The Bismarck desperately filled the air with flak, so the pilots dived even lower, hugging the water and hoping the ship’s guns couldn’t aim that low. In a worst case scenario, they might just survive a sea crash.

At 2,000 yards, Moffat prepared to launch his only torpedo, when he heard a voice, “Not yet, Jock! Not yet!”

Moffat jerked and looked around. It was his Observer, Flight-Lieutenant JD “Dusty” Miller. The man was standing on the right wing with his butt in the air, head somewhere below the plane’s belly.

Moffat understood. The sea was rough. If his torpedo hit the crest of a wave, it could veer off course. Miller wanted to make sure it fell into a trough so their only weapon had a chance. But the longer they took, the greater their chances of getting hit.

“Let her go, Jock!”

Moffat released his torpedo.

“We’ve got a runner!” Miller screamed.

The Bismarck turned left sharply – a mistake. The torpedo hit the left rear, tearing a hole through the hull and causing rivets to pop off the bulkhead. The ship’s twin rudders, angled for the turn, jammed. Power died, forcing the engineers to restart everything. Mechanics tried to fix the rudders, but too much water was rushing in.

With rudders stuck at 12° to port, the Bismarck turned around and headed back toward the British fleet. Within minutes, it was turning around in circles. Lütjens informed Berlin and vowed to die fighting.

The British showed no mercy. They surrounded the Bismarck, forcing it to fire in all directions. Unable to maneuver, it became a sitting duck and ran out of ammunition at 9:31 AM the next day. Despite the lack of return fire, the Royal Navy kept up their barrage till it sank at 10:39 AM.

They did try to rescue survivors, but a U-boat scare forced them to retreat with only 115 Germans (out of 2,092). The rest were left to their fate. Germany only found out about the sinking from a News Network at around noon. By the time they reached the scene, only five more men were alive to be retrieved. But not Lütjens. He kept his word, as did Lindemann.

Thanks to an outdated biplane, the Bismarck’s only combat mission lasted a mere 215 hours. From that moment on, naval warfare changed forever. The plane was now as important as the ship in naval warfare.