It’s hard to imagine a time when vaccines didn’t exist. However, up until the Second World War, they were few and far between. It wasn’t until the US Army decided to collaborate with medical experts and industry professionals that one was finally developed to prevent one of the world’s most common illnesses: the flu.

Disease in the military prior to World War II

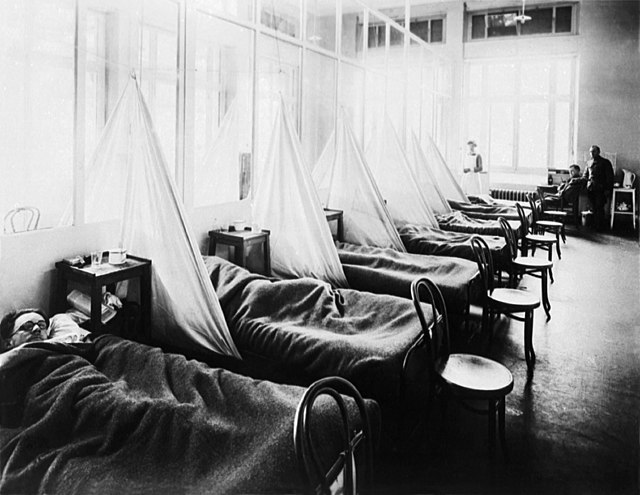

Before World War II, those serving on the frontlines perished more from disease than injury. The situation was improved with slightly better sanitary conditions during the First World War, but they still couldn’t prevent the spread of one of the deadliest illnesses of the 20th century: the 1918 influenza pandemic.

The pandemic caused an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide, and part of the reason for its spread was the fighting in Europe. The Great War saw soldiers from across the world travel to the continent in an influx it had never before witnessed. This allowed for not only the introduction of new illnesses to the population, but also their rapid spread – the US Navy saw about 40 percent of sailors affected, while the US Army wasn’t far behind, with an infection rate of 36 percent.

Need for a flu vaccine

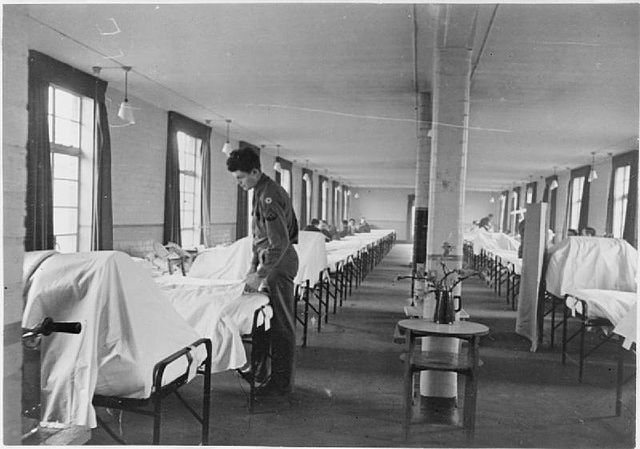

World War II was the beginning of even more epidemics across Europe. The likes of diphtheria spread like wildfire, and the US military realized it was losing more troops to illness than to fighting. This spurred a partnership between the US Army, industry and academia, allowing for unprecedented levels of innovation against wartime disease threats.

Ten vaccines were developed or improved during this time, with more than one-third used to combat preventable diseases. One protected against botulinum toxoid, created in response to false intelligence that the Germans had loaded their V-1 bombs with the toxin behind botulism. Another was the Japanese encephalitis vaccine, developed in preparation for an Allied landing in the country.

During this time, Scottish physician Alexander Fleming presented a medical innovation that changed the world: penicillin. However, the most significant development to come from the war effort was that of the flu vaccine.

Organizing a federal commission

In 1941, fearing another pandemic, the US Army organized a commission. It was part of a much larger network of federal vaccine development programs, which enlisted a slew of specialists, in an attempt to target the flu, measles and the mumps, among other diseases.

The commission pulled together knowledge of how to isolate, grow and purify the flu virus, so that the development of the vaccine could be fast-tracked. It was headed by virologist Thomas Francis, Jr. Scientists could work from home, affording the US military access to expertise and facilities in the civilian sector.

Seeing it as part of their wartime duty, manufacturers offered to work with the commission for little-to-no profit. With the medical industry as an active partner, a new research format was formed, effectively turning scientific findings into actual working vaccines.

This, paired with the fact intellectual property rights weren’t a barrier, resulted in the quick development of the vaccine. Francis and the other directors could transfer people and resources to projects deemed the most important, allowing for coordination in all phases of the development process. The result of these efforts was an FDA-approved flu vaccine in under two years – the first licensed in the United States.

Lack of cooperation in the post-war era

Following World War II, cooperation between the US Army, manufacturers and medical professionals continued, resulting in the development of a variety of vaccines during the middle of the 20th century, including those targeting meningococcal meningitis and adenovirus.

However, this partnership disintegrated toward the end of the 1900s. Legal, political and economic changes during the 1970s and ’80s caused major disruptions, and without full cooperation, vaccine development stalled.

More from us: Operation Long Jump: The Alleged German Plan to Assassinate the ‘Big Three’

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

Some existing programs were even discontinued.