The Hussite war movement didn’t terrify its opponents solely because it represented a break from the Catholic church: the manner in which the movement went into battle and the equipment that the soldiers used was also extremely frightening to their enemies.

Under the rebellion’s leader, an intense man named Jan Zizka, the Hussites fought for release from the strictures of the Catholic church. It was in approximately 1420 that the stirrings of Protestantism began, as people in Hungary slowly but steadily decided they wanted to be free of the Papacy.

Long before anyone had heard of Martin Luther, a dissident named Jan Hus became a popular hero to those who wanted church reform. But the more people pressed for it, the more the Catholic church pushed back, making it clear that any thoughts of rebellion would be dealt with harshly. The church burnt dissidents, like Jan Hus, at stake to prove their point.

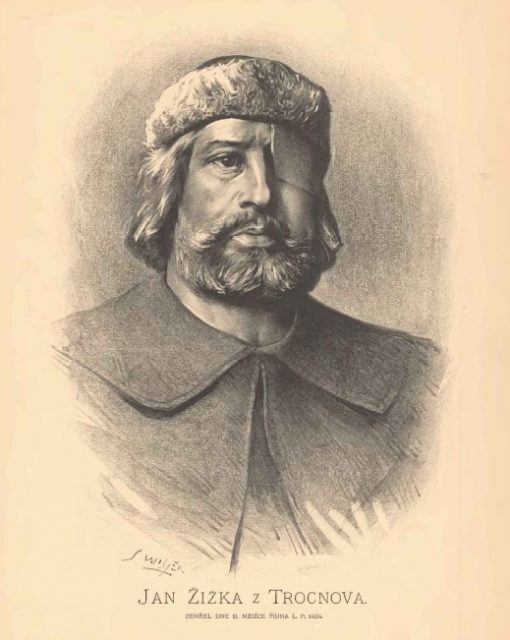

In Hungary, Hus’s death provoked outrage. Those who had followed him formed an uprising, led by Zizka, that ended in the ousting of King Sigismund, whose troops could not fend off the angry mobs. When Zizka corralled these people into a formal, cohesive group, the Hussite movement was born. Zizka’s one-eyed, intense visage became the popular face of this movement of religious zeal.

Zizka knew how and when to stage battles but perhaps, more importantly, he understood the value of the Hussite war wagons. These vehicles were the perfect defense structures with which to fend off the enemy and secure victory.

When placed in a strategic setting, these wagons became almost impenetrable. The Hussite army would interlock their wheels, creating a kind of wall behind which the soldiers took up positions. Furthermore, each wagon had holes strategically cut in its sides so guns could protrude. Soldiers could safely stay within the ring of wagons and fire on the enemy at will. Once the opposing force was down on its heels, the Hussites descended; many battles were fought – and won – in this way.

The wagons led directly to the first Hussite victory, in March, 1420. King Sigismund did not take his ousting lightly. He tried to push back in July that year, yet his army could not penetrate the war wagons and he was again driven back by the Hussites.

Until 1427, Zizka led his men into many battles and achieved several victories. Tired of always defending their own turf, the Hussites invaded Saxony and Silesia in 1428. While they came close to defeat on several occasions, Zizka’s leadership and religious vigor saw them through many successful campaigns.

Perhaps inevitably, success led to infighting and corruption. Many Hussites lost sight of the ideals that had, in the beginning, led them to challenge the church and the king. So when Sigismund launched yet another attack in 1431, the Hussite soldiers managed to repel him, but only barely.

More infighting broke out. By 1434, Zizka was completely blind. Finally, a faction called the Noble Ultraquists cobbled together an army and took on the Hussites at the Battle of Lipany. The Ultraquists staged a mock surrender, convincing the war-fatigued Hussite army to advance from behind their shield of wagons. In the ensuing battle, the Ultraquists were quickly victorious.

It took several years but, at long last, King Sigismund was back on his throne and the Catholic Church was once again firmly in charge. For a while, at least.