“Soldiers, sailors and airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force: You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you.”

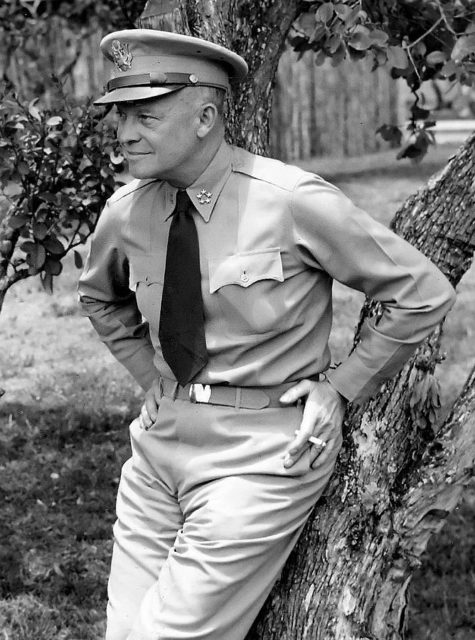

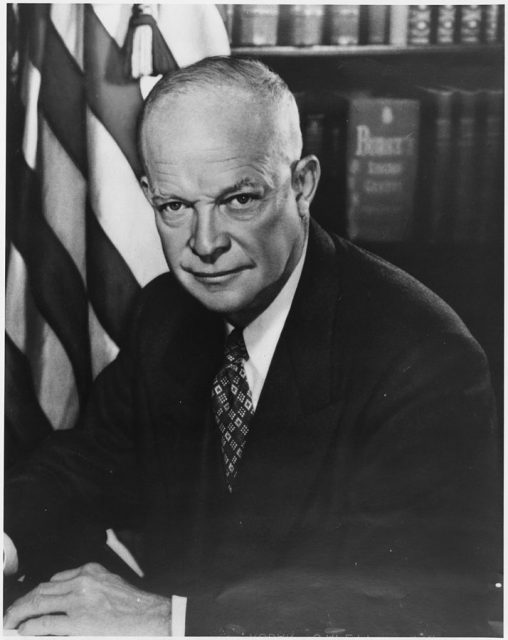

So began General Eisenhower’s last address to the troops before the D-Day invasion of Normandy. Hundreds of thousands of men were moving on his command, and many of those men would be under fire within hours. “Ike” knew that for many of them, it would be their last day on Earth. For many others, grievous wounds would mar them physically, mentally and emotionally for life.

With the job of commander of a great force come many perks: a chauffeur, a warm bed, as much of the best food and drink as you want, and meetings with world leaders and other leading lights. For Ike in particular, it came with as much coffee and as many cigarettes as he could go through.

Ultimately, for the general in command, the ability to exercise your own plans and ideas above those of others is a privilege of the job, one toward which many military men have striven.

The flip side of all of that is the knowledge that no matter how successful your plans are, whether they are made in conjunction with others or not, you are the one that bears the ultimate responsibility for the lives of your troops. As it has been throughout history, that was the case for Eisenhower prior to D-Day.

Before the invasion, estimates of potential casualties for the cross-Channel invasion ran into the tens of thousands. Churchill, Roosevelt, and Eisenhower were all intensely aware of not only the physical cost, but also the consequences of failure.

Should the Western Allies fail to establish themselves on the Normandy coast, the war might drag on for years. Hitler would be able to shift many of his troops in the West to the Russian Front, and while perhaps it was not a given that the Soviets would lose, at the very least, hundreds of thousands more people would die.

No one could foresee the future. Perhaps Stalin and Hitler, tired of war and absolutely dismissive of anyone’s wishes but their own, might sign another non-aggression pact, as they had to the world’s surprise in 1939. Even if that were only temporary, Europe might suffer for years or decades longer.

Though history records Roosevelt, and especially Churchill, having deep doubts and fears about “Operation Overlord,” and taking time to write speeches for the public in case the landings did fail, the power to order “Go” and all subsequent movement was in Eisenhower’s hands, and he felt it keenly.

He too had a short note for the press in case the landings failed, in which he took all responsibility upon himself.

Most people familiar with the D-Day story will know about the agonizing days before the invasion when the weather might have prohibited the landings for weeks, if not longer. Allied meteorologists thought there might be a window of good weather on June 5-6, but they were not sure.

All of Ike’s war chiefs were there: Montgomery, Leigh-Mallory, Bedell-Smith, and others. After Stagg’s report, they gave their advice – most said go, some demurred. All eyes were on Eisenhower.

“OK, we’ll go.” History records the rest.

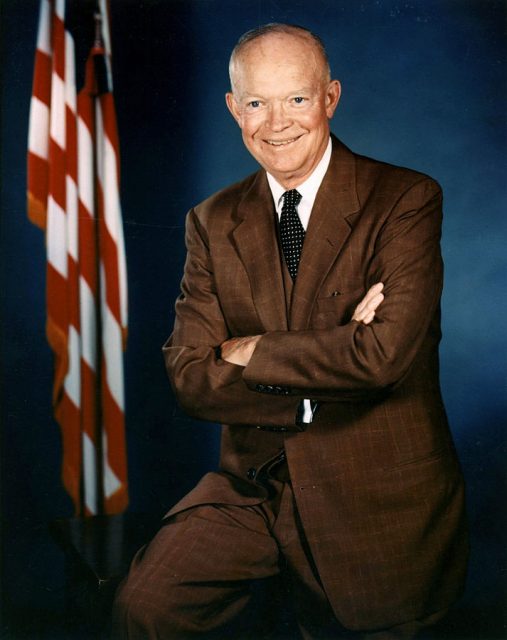

Eisenhower spent some time after the war as military governor of the American Zone of Occupation in Germany. He then returned to the States to become Army Chief of Staff when George Marshall became President Truman’s representative overseas and later Secretary of State.

Of course, Ike famously won the Presidential election of 1952 and was re-elected in 1956. Throughout his time in power, Eisenhower visited other nations, but never publicly returned to Normandy or any of the other battle sites of the Western Front.

This was not done out of callous disregard. Eisenhower was a sensitive man, and in his position as President of the United States, was afraid that emotion would overcome him should he pay a visit to Normandy or other places.

It was not until some twenty years after the war, and four years after leaving the White House, that Eisenhower returned to the French beaches that began the Allied effort in Western Europe. Of course, this would be big news, and the only one that Eisenhower trusted to report on it was America’s most trusted newsman, Walter Cronkite.

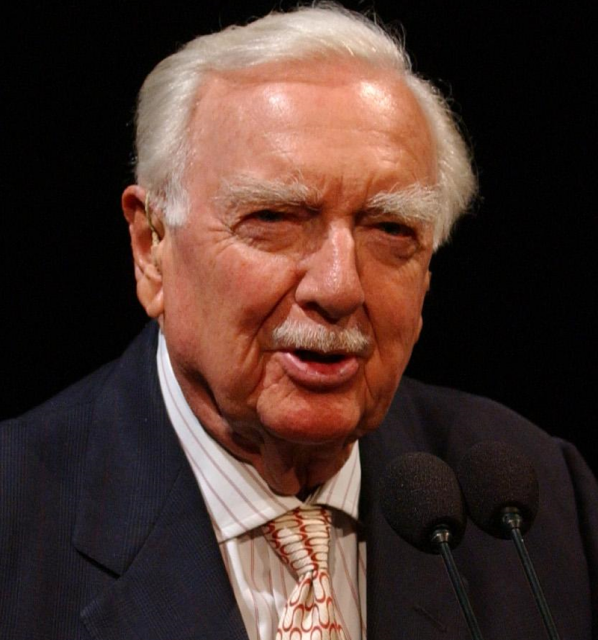

Cronkite had “made his bones” as a reporter during WWII. He had taken part in the Allied landings in North Africa and had flown with the American and British bomber fleets over Europe and Germany. He reported on the Normandy invasion from Normandy itself, and would land in a glider with troops of the 101st Airborne in Operation Market Garden.

Walter Cronkite knew the cost of war first hand. That, combined with his status as an anchorman by 1964, convinced Eisenhower to let Cronkite accompany him as he went back to France for the invasion’s 20th anniversary.

Cronkite interviewed the former President before the visit to the beaches, starting with when planning had begun.

They sat in the former war room where much planning took place and followed in the footsteps of the men who undertook the operation, traveling by boat across the Channel.

Ike told stories about many of the people involved in the planning process and others, both powerful and humble, from Churchill’s express wish to accompany the troops on D-Day–and Ike’s having to ask the King of England to forbid his Prime Minister to go–to the famous meeting that took place on the 5th with men of the 101st Airborne.

In one of the weird coincidences of history, many of the men in that famous picture were the men of the famed “Easy Company” of Band of Brothers fame.

Ike went into detail about the planning and logistics of the landings as they approached the beaches, and told Cronkite about the midget subs off the British coast, which few people knew about at the time.

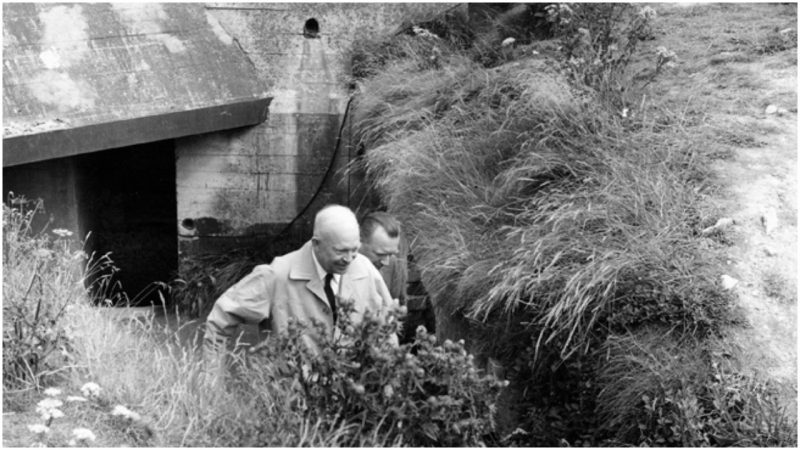

Cronkite escorted the Supreme Commander to many of the famous spots of the landings, including some of the German installations, where Ike described what must have been going through the Germans’ head when they saw the armada of ships approaching the coast.

The famous D-Day movie The Longest Day had come out in 1962 and Ike was quite familiar with it, having been invited to the premiere. Cronkite and Eisenhower sat in a German bunker very similar to that of German officer Werner Pluskat, who was depicted in the movie, seeing 5,000 ships “Heading directly for me!!”

Then Ike visited Omaha Beach – in a jeep. Though much of the beach was cleared of the public, in the footage you can see people strolling about in the background. Imagine what must have been going through their minds when they saw an American jeep cruising down the beach, being driven by the former General and President Eisenhower!

Just before they left the beach, Cronkite asked the General about the casualty totals of D-Day, and Ike ran through what he knew. The totals didn’t come in until much later after the chaos had stopped, but they were “fortunate” that the worst estimates hadn’t come to pass.

The pair then went off into the Normandy countryside, and describe the hedgerow breakout and the great slaughter of German troops which took place during “Operation Cobra” weeks after the landings.

Lastly, Eisenhower visited the American Cemetery above Omaha Beach, where he and Cronkite walked among the gravestones, Cronkite occasionally reading the tombstones. At the time, there were about 9,000 men in the graveyard.

“Walter, D-Day has a very special meaning for me, and I’m not referring to the anxieties of the day…where you knew that many hundreds of boys were going to die or be maimed.” He went on to talk about how his son had graduated on June 6th, 1944 and had lived a very full life since then.

Ike observed that that full life was due to men like the ones that were lying in front of him and Cronkite. Men who had come across the Atlantic for the second time that century to save Europe from tyranny.

Read another story from us: WWII Hero Recounts the Normandy Invasion

The fact hit Eisenhower that many of the men that lay there never knew the joys of a full life. They had been cut down in their youth for the ideals of freedom – not for fame or the aggrandizement of a dictator, but so that others, like Eisenhower’s son, could live in peace. He went on to acknowledge that “these people have given us a chance so that we can do better than before.”