Born to Fly

Jesse LeRoy Brown was born on October 13, 1926, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi into a poor family with a steadfast commitment to educating their children. As one of six children, the young African-America grew up in the deep south enduring all the struggles associated with segregation in both his schooling and his military career.

When he was six years old, his father took him to an air show which lit a flame for flying in Brown. Growing up, he was inspired by stories of famous black aviators such as Eugine Jacques Bullard and Bessie Coleman. When he was 11 years of age, Brown wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt to complain about African-Americans not being allowed to join the Army Air Corps. To his surprise, he received a reply from the President’s office saying his views were appreciated.

Brown graduated as the salutatorian from his high school in 1944 and enrolled at Ohio State University. In 1946 while there, Brown learned about the Aviation Cadet Training Program which enrolled college students to gain a commission as naval aviation pilots. As he was attending an integrated college, his status as an African-American did not prohibit him. Despite resistance from military recruiters and fellow cadets, he passed the entrance exam.

To say that he received his fair share of vitriol for doing so would be an understatement. However, Brown would not be deterred from his dream, and by October 1948 he had earned his Naval Aviator Badge. His achievement was covered nationally in newspapers who wrote Brown had broken the “color barrier” which had prevented black people from becoming naval pilots.

A Stellar Pilot

In June 1950, the North Korean Army poured across their border into South Korea with catastrophic results. The United Nations Security Council voted to send in military aid to help the South Koreans, and all US Navy units were placed on alert.

Brown had been assigned to the aircraft carrier the USS Leyte which was on maneuvers in the Mediterranean Sea. In August they were ordered to sail for Korea to assist the American ground forces there, arriving in October 1950.

The Chinese joined the fray in November to help the North Koreans. 100,000 Chinese troops surrounded approx 15,000 American Marines. The pilots were flying dozens of close air support missions every day to protect the area.

On December 4, 1950, in harsh winter conditions, Brown and five other pilots were supporting US Marines on the ground. Flying low and searching for targets in the snow, the planes were vulnerable to small arms fire from below.

Brown’s wingman radioed him to advise there was fuel leaking from his aircraft. Likely due to the small arms ground fire, Brown’s plane was losing fuel pressure and became increasingly hard to control. He dropped his external fuel tanks and rockets before crash-landing onto the frozen Korean countryside. The aircraft came apart upon contact and burst into flames. Remarkably, Brown survived. He was, however, trapped by a crushed leg underneath the fuselage.

Rescue at All Costs

Brown’s wingman, Thomas Hudner, saw Brown waving from the ground to indicate he was still alive. The other pilots circled overhead looking out for Chinese troops as they were 15 miles behind enemy lines. Hudner attempted to assist his friend over the radio but realizing he needed to get on the ground if he was to have any effect in trying to rescue his wingman, Hudner did the inexplicable. He intentionally crashed his plane nearby and ran to help Brown.

Hudner tried to free Brown from the wreck and then attempted to fill the cockpit by hand with snow to quench the fire. In intense pain and losing blood, Brown was falling in and out of consciousness. A rescue chopper had been deployed and arrived at the scene, but they were still unable to free the wingman. Brown asked them to amputate his leg before he lost consciousness for the last time. His last words were “tell Daisy I love her.” As darkness fell, the rescuers were compelled to leave as the helicopter could not fly at night.

The next day, Hudner pleaded for the opportunity to go back and try to recover Brown’s body. Fearing an ambush, Hudner’s commanders refused permission – they could not allow the loss of more pilots or aircraft. Not wanting the body or plane to fall into enemy hands, the US Navy dropped napalm on the position of their fallen comrade. Brown was the first African-American US Navy officer killed in the war.

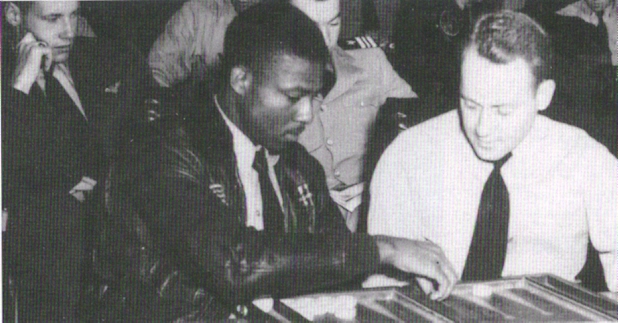

Hudner for his actions in trying to save his wingman was awarded the Medal of Honor. Brown for his service in combat became the first African-American US Navy recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

In 1973, the Navy commissioned the USS Jesse L. Brown in his honor. Brown’s persistence to achieve his dream and his exceptional service is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military and he deserves his rightful place in history.