It happened in the city of Gdańsk, Poland – formerly the Free City of Danzig. It was not always Polish. It was part of the German Empire until the end of WWI and the signing of the Versailles Treaty. Besides paying substantial reparations, the Germans also had to give up territory.

Poland was founded in the 10th century but was partitioned in 1795 by Austria, Prussia, and Russia. The Poles wanted their country back, but they did not want a landlocked nation.

After WWI the Allies split Germany in half. Poland acquired the well-developed seaport of Danzig which upset the Germans, but the Allies did not care. As far as the victors were concerned, Germany should have thought of that before marching through neutral Belgium and Luxembourg to attack France.

Danzig came under the protection of the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations. Poland had a binding customs union over it, as well as control of its transportation and communications infrastructure. However, the majority of it’s citizens remained ethnic Germans.

They voted the local branch of the Nazi Party into power in 1933. Due to the League and Poland’s authority, however, life went on as usual; although the Poles were worried. They attempted to increase the number of soldiers at the garrison, but the League would have none of it – forcing Poland to withdraw its reinforcements.

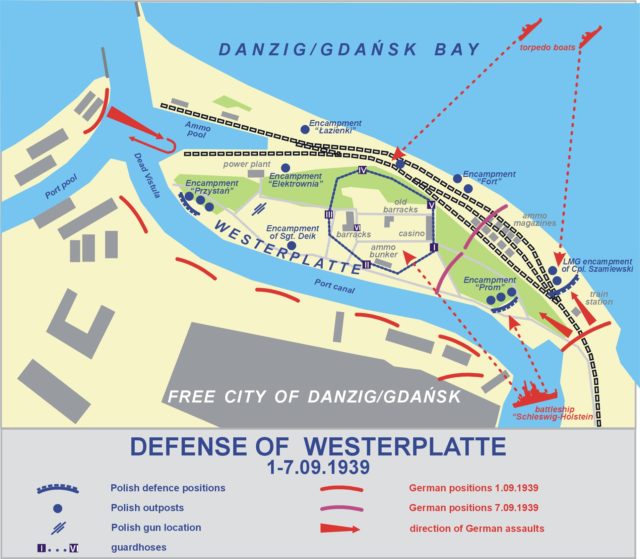

In late August 1939 the German battleship SMS Schleswig-Holstein entered the port on a “goodwill mission.” It docked at the Westerplatte peninsula beside the Polish Military Transit Depot (WST).

The WST was separated from the port by a harbor channel connected to the mainland by a small pier. Cut off from the rest of Danzig by a brick wall; it was protected by five guardhouses in the surrounding forests, together with trenches, barricades, and military buildings.

Aboard the Schleswig-Holstein Lieutenant Wilhelm Henningsen was in charge of 225 German Marines. In the city, Police General Friedrich-Georg Eberhardt of the SS-Heimwehr, the Nazi police, had a force of 1500 men. The Polish police had assured the Germans Westerplatte could be taken in 10 minutes.

Major Henryk Sucharski and Captain Franciszek Dąbrowski were in charge of the garrison. Despite the League, Poland had increased its troops from 88 men to 210 by 1939.

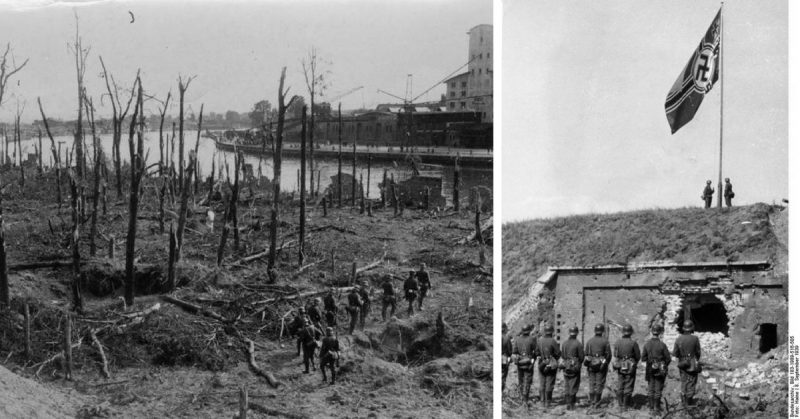

On September 1 at 4:48 AM the Schleswig-Holstein fired – punching three holes in the WST perimeter wall and blowing up oil warehouses. The German Marines attacked when the land bridge’s railroad gate was blown up but they went straight into an ambush. Barbed wire blocked their advance as the Polish defenders gunned them down.

The SS-Heimwehr had set up machine gun nests on top of warehouses across the canal, but the Poles destroyed them with their lone 76.2 mm field gun.

The Schleswig-Holstein then knocked it out. By 6:22 AM, the ship received distress calls from the surviving Marines who were retreating. More German fire power was needed.

They launched 90 x 280mm shells, 407 x 150mm shells, and 366 x 88mm shells. Sucharski ordered his men to retreat from the Wał and Prom outposts, and for a time, also the Fort.

The Marines launched their second attack at 8:55 AM; straight into mines, barbed wire, fallen trees, and even more machinegun fire. The Poles focused their defense around the New Barracks in the middle of Westerplatte. Exhausted, the Germans gave up at noon.

On the first day of the battle, there were 50 dead Germans (including Henningsen) and 1 Pole although three later died of their wounds in a German hospital. The Germans might have sustained more casualties, but Sucharski wanted to save on ammo. So much for Danzig being taken in 10 minutes.

September 2: The Schleswig-Holstein blasted Westerplatte’s park to bits. They left so many craters, the German Marines could not launch another ground assault.

September 3: 60 Junkers Ju 87 dive bombers took to the sky. They destroyed a guardhouse, the defenders’ radio, and the WST’s entire supply of food. Satisfied that had done the trick, the Marines attacked later that evening. However, the bombardment had killed eight Poles only.

September 4: The T-196 German torpedo boat fired from the sea – on the opposite side of Westerplatte to the northeast. It was too much. Sucharski abandoned the Wał. The Fort position became their only defense against further attack from the north.

The situation was hopeless. The defenders were supposed to hold out for 12 hours, yet after four days there was no sign of reinforcements. They had no food. By September 5, Sucharski, shell-shocked, considered surrendering. Dąbrowski opposed him and took over command.

The Germans tried again the following day. They set fire to a train on the land bridge then drove it toward the oil cisterns. It might have worked, except the driver lost his nerve and decoupled his cars before reaching the target. Instead, the forest was set on fire lighting up the German positions nicely – the Poles could not miss. The Germans tried the same tactic later that afternoon but again failed.

Sucharski was back in control, but many of his men were suffering from gangrene due to lack of medical care. News that the German Army was outside Warsaw reached them.

The Germans launched their final bombardment on September 7 at 4:30 AM… and kept it up until 7 AM. The silent aftermath was deafening but the Germans refused to send Marines in – they had learned their lesson.

At the end of the battle, there were 200 to 300 dead Germans against 15 to 20 Poles. The Poles finally raised a white flag at 9:45 AM. The Germans were so impressed with the defenders that Eberhardt let Sucharski keep his ceremonial saber