The Battle of Britain was witness to many heroic stunts from numerous gallant servicemen who metaphorically danced with Death for the sake of defeating an overwhelming enemy.

They defied common sense, through actions that spoke much louder than words, braving the smoldering stares of death and surging forward in moments that would have caused many to retreat.

John Hannah was such a man. And this is his story.

The Scottish airman was born in Paisley on November 27, 1921. After completing his education at Victoria Drive Secondary School, Glasgow, he enlisted with the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939.

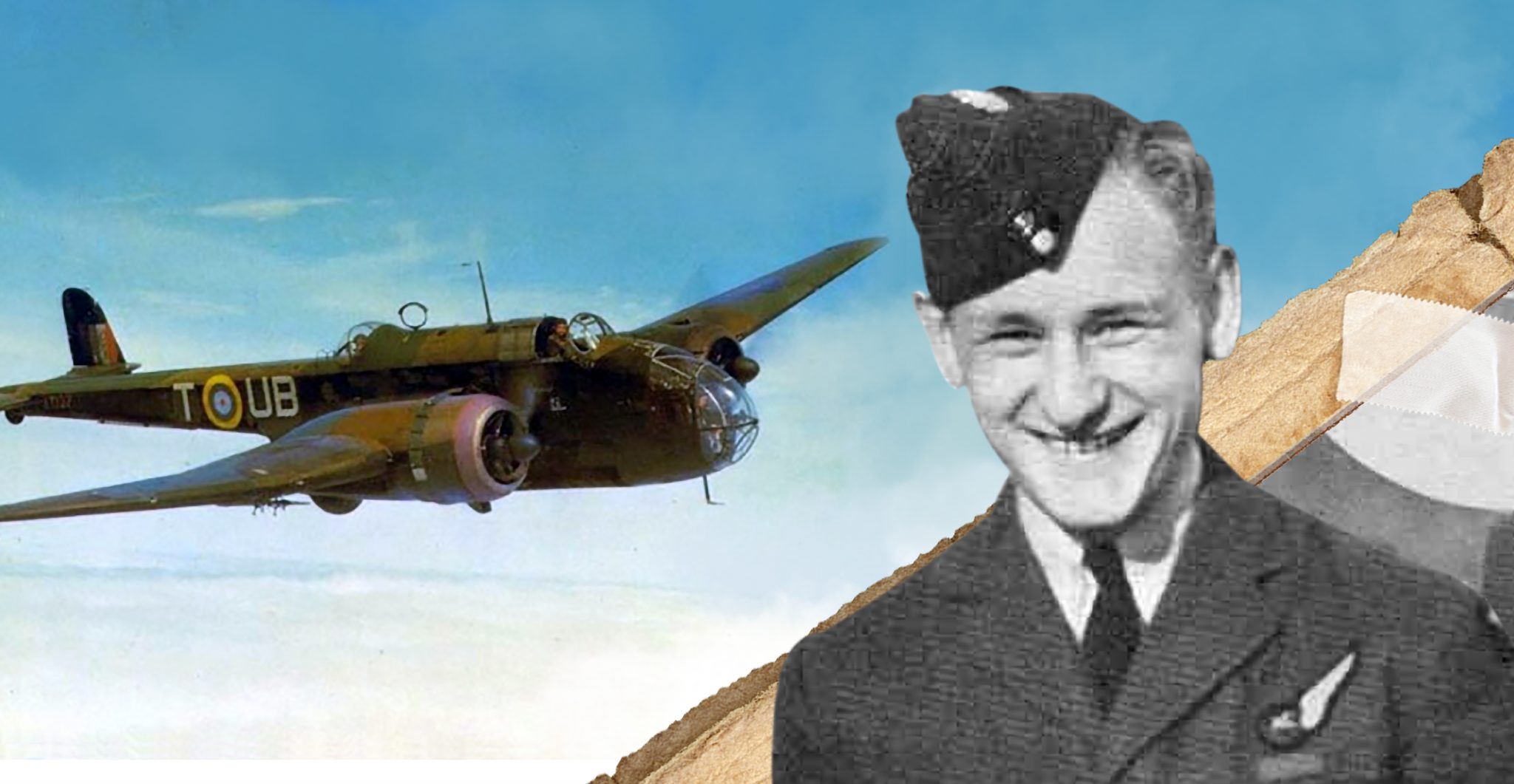

In 1940, he became a sergeant serving with the No. 83 Squadron of the RAF as a wireless operator and aerial gunner aboard Handley Paige Hampden bombers.

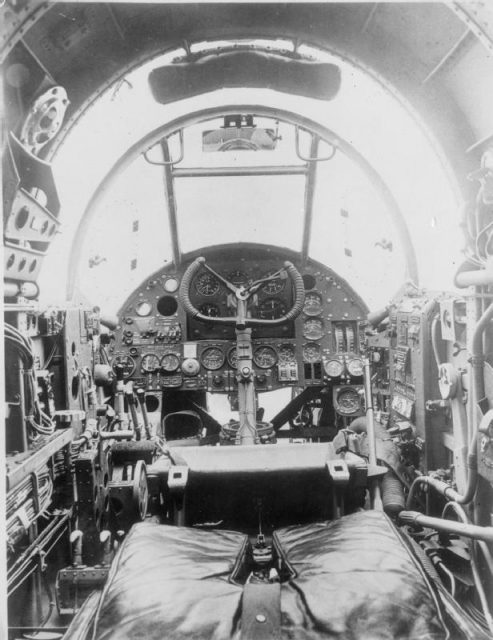

The Hampden bomber was a twin-engined medium bomber nicknamed “The Flying Suitcase” for its cramped spaces which did not provide the best working environment for its four-man crews. It was, however, a primary bomber aircraft for the British during the opening stages of WWII.

On September 15, 1940, the RAF launched an attack on German forces in the city of Antwerp, Belgium. Antwerp had been occupied by Germany since May 1940 and was particularly important because of its port.

That night, during the attack, Hannah’s bomber crew successfully dropped bombs on German barges in the target location.

But as soon as they dropped their bombs, German anti-aircraft guns engaged them. The Hampden took a direct hit from the intense enemy fire. It turned out that an enemy projectile had struck its bomb compartment, and a fire was rapidly taking over the plane.

Hannah’s cockpit was blazing, and with the bomber’s fuel tanks also pierced, the aircraft was at the brink of explosion.

John Hannah managed to make it to a pair of fire extinguishers. But he soon realized that the rear gunner, George James, had abandoned the plane as its floor melted in the fire.

There was an opportunity for Hannah to also jump out of the plane to relative safety. Common sense would have suggested taking that opportunity. However, Hannah instead faced the fire, brandishing the extinguishers.

Over an intense period of ten minutes, Hannah sprayed in all direction, working hard to stop the blaze from destroying the aircraft. When the extinguishers were exhausted, the fire was still burning.

Hannah grabbed his logbook and began to beat out the fires. When the logbook was itself consumed by the flames, he used his bare hands.He struggled in the midst of exploding ammunition, blinding heat and choking fumes. But he didn’t stop. When the fumes began to asphyxiate him, he managed to reach his oxygen supply.

By the time he had quenched the flames, the floor of his position was completely melted away, and his face and hands had been terribly burned.In intense pain, he crawled through the plane to the navigator’s position only to discover that the navigator had long since abandoned the bomber, too. That left just Hannah and the pilot.

He retrieved the navigator’s log and maps and passed them to the pilot. With Hannah’s assistance, the pilot successfully landed the badly-damaged aircraft back at their RAF base.Hannah was promptly rushed to the hospital for urgent treatment. On October 1, he found out that he was to be honored with the Victoria Cross.

At the time of the event over Antwerp, Sergeant John Hannah was only eighteen years old. His baffling courage, determination, and devotion to duty made him the youngest recipient to be thus honored for an aerial operation. He was also the youngest Victoria Cross recipient of the Second World War.

After he recovered from his wounds, he remained with the RAF. But the scars of 15 September 1940 haunted him for the rest of his short life. The burns had weakened his immune system, making him susceptible to diseases.

In late 1941, he contracted tuberculosis. In December 1942, his waning health resulted in his discharge from the RAF. The RAF sent him off with a full disability pension.

Read another story from us: 10 Luftwaffe Aircraft Certainly Gave the Allies Cause for Concern

Hannah took up taxi driving, but was unable to keep up with the job due to his health. In March 1947, he ended up in Markfield Sanatorium, a health institution in Leicester. He died on 7 June 1947, leaving his wife and 3 daughters behind.

His burial place is found in the churchyard of Saint James the Great Church in the village of Birstall, north Leicester, and his Victoria Cross is on display at the RAF museum in London.

His gravestone bears an inscription that says: “Courageous Duty Done In Love, He Serves His Pilot Now Above.”