Any Star Trek fans reading this article will know about the Jem’Hadar, the artificially created warriors who showed no fear in battle. In one episode of Deep Space Nine, the leader of a Jem’Hadar squad gives them a “pep talk”: “I am First [Name], and I am dead. As of this moment, we are all dead. We go into battle, to reclaim our lives. This we do gladly, for we are Jem’Hadar – remember, victory is life!”

It’s no coincidence that the creators of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine chose the name “Jem’Hadar” for their warrior species. “Jemadar” was a rank of the Indian contingents in the British Imperial Army.

The rank was similar to a US Second Lieutenant crossed with a Platoon Sergeant, though the Imperial Army was a colonial one. A British officer was often in command above, but in conjunction with, the jemadar.

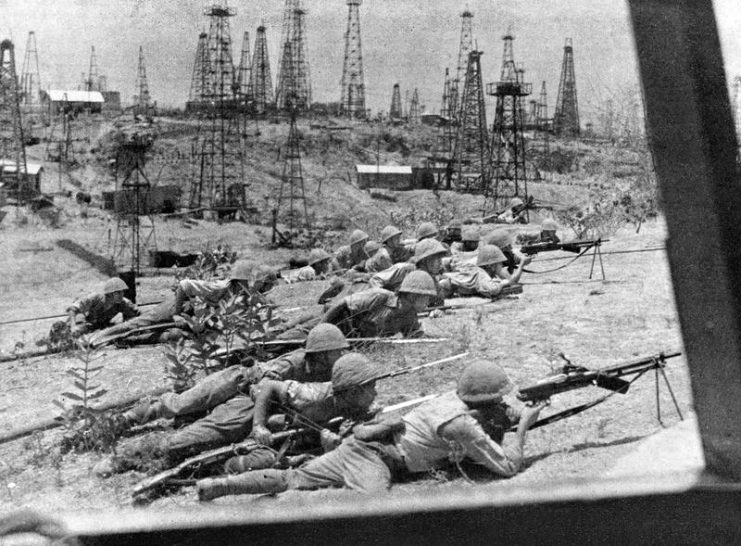

Indian troops served in large numbers during WWII, and in virtually all theaters of the conflict. In 1939, there were just over 200,000 Indian volunteers. At the end of the wars, there were over 2.5 million. The British Indian Army was the largest all-volunteer force in military history. The highest citation for bravery in the British Empire, the Victoria Cross (“VC”), was awarded to 17 of them.

Volumes have been written about why so many Indian men joined the British Army when Britain held India as a colony.

There isn’t space here to detail all the reasons, but a primary one was the fact that many of the volunteers came from warrior cultures, where military service was a given for young men. One of the other reasons was that a military career could lift a man out of the crushing poverty that was, and still is, the reality for many in India.

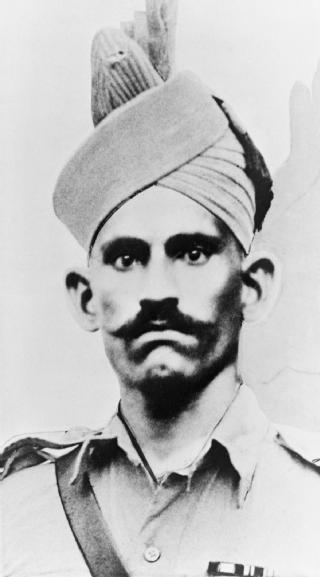

One of those courageous volunteers was Jemadar Rao Abdul Hafiz Khan. He served in the 9th Jat Regiment. The Jats were from the borderlands of today’s India and Pakistan and included men of Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh faiths.

Abdul Hafiz was Muslim, but many of the men he served with were not. In many ways, the British Army effectively brought together men from different cultures for a united purpose.

The Jats served in North Africa, Ethiopia, Malaya, Singapore, Burma, and Sumatra throughout the war. They also served in India, where Jemadar Abdul Hafiz was awarded his Victoria Cross. Two other men were also awarded the VC in India. They were all awarded the citation for the Battles of Kohima and Imphal, two savage engagements which were fought on the Indian side of the border with Japanese occupied Burma.

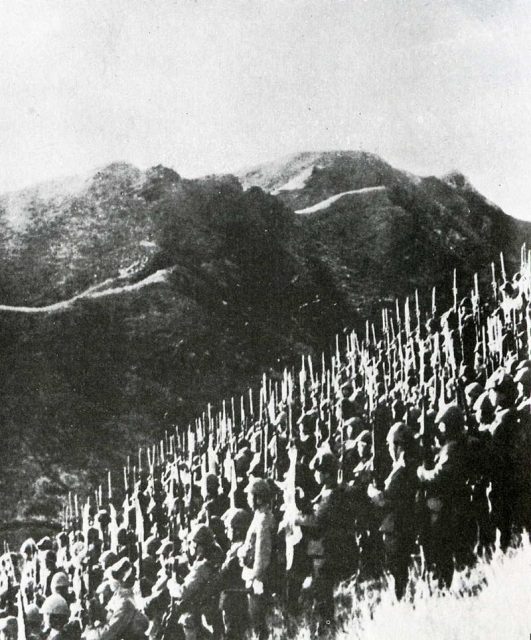

These two battle sites are close to each other and took place at the same time. They are noted for the many close-combat actions that took place.

On April 6, 1944, Abdul Hafiz was at Imphal when he was ordered to take his platoon up a steep hill and attack a Japanese position which dominated the area. The hill itself was steep, but the enemy position was steeper still, being on an escarpment at the peak. The Japanese had launched several patrols from that position and claimed a number of lives.

No one knew for sure how many Japanese were at the top of the hill. They only knew that they had 40 men with which to dislodge them. Halfway up the hill and under heavy fire, Jemadar Abdul Hafiz decided enough was enough. As he ran ahead of his men, he tossed grenade after grenade and fired round after round until he was face-to-face with a Japanese machine gun position.

The jemadar had been shot in the leg on the way up the hill, but that didn’t stop him. He pushed the barrel of the enemy machine gun skyward and cut the throat of the man firing it with the other hand. He then killed the other men in the machine gun crew in hand-to-hand combat.

Abdul Hafiz’s men were right behind him, firing at Japanese positions all around. One man carrying a Bren light machine gun fell, and Abdul Hafiz grabbed the fallen man’s weapon.

A Bren gun was designed to be fired from a defensive position, or in a prone position to provide covering fire during an attack. The Bren weighed over 20 pounds (over nine kilograms) and was unwieldy, to say the least.

Nevertheless, the jemadar picked up the Bren and began firing from the hip as he ran across open ground at the top of the hill. Eventually, the Japanese lost their will to fight in the face of this man who seemingly could not be stopped. The surviving Japanese ran as fast as they could to positions further away.

As Abdul Hafiz prepared to follow them, he was struck in the chest by a bullet from another Japanese machine gun nest further away. As he died, he told the men gathered near him: “Re-organize on the defensive positions! I will give covering fire!”

Today his Victoria Cross is on display at the Imperial War Museum in London, alongside those of many other heroes.